In its most benign form, artificial intelligence (AI) is just another tool artists and collectors can use for advanced research. It’s not truly thinking up novel works of art; instead, AI quickly scours the internet’s data and images to generate answers to queries. It learns from data, identifies patterns, and makes decisions or predictions based on that learning.

But on a broader level, the technology raises new and significant questions about authorship, originality, and the real value of creativity. Have we, all of a sudden, devalued the skills that took human artists and other creative individuals many years to develop?

A growing number of artists and authors across the U.S. are suing AI companies for copyright infringement related to the use of their work in training generative AI models. In January 2023, illustrators Sarah Andersen, Kelly McKernan, and Karla Ortiz filed a landmark lawsuit in California challenging the unauthorized use of their art. Similar lawsuits have been filed in New York, including a 2023 class-action suit by The Authors Guild and 17 prominent authors, such as John Grisham, Jodi Picoult, and George R.R. Martin, against OpenAI. The authors claim that this unauthorized use constitutes “systematic theft on a mass scale” and threatens their livelihoods by enabling AI to generate content that mimics their writing styles.

It’s also notable that in June, the first major movie studios, Disney and Universal, sued an AI image generator with tens of millions of registered users for copyright infringement, bringing Hollywood into the broadening legal landscape over generative AI. The movie studios contend that AI company Midjourney used copyrighted works to train its software, which allows people to create images (and soon videos) that incorporate and copy Disney’s and Universal’s famous characters. “Midjourney is the quintessential copyright free-rider and a bottomless pit of plagiarism,” the companies said in the lawsuit, which was filed in U.S. District Court in Los Angeles.

The End of Art? Not so Fast!

So, while the court system attempts to balance the scales, should collectors and artists be wary? As with almost everything concerning the valuation of art, the answer is nuanced. You should consult smart, trustworthy art curators, gallerists, and dealers to stay informed about current trends.

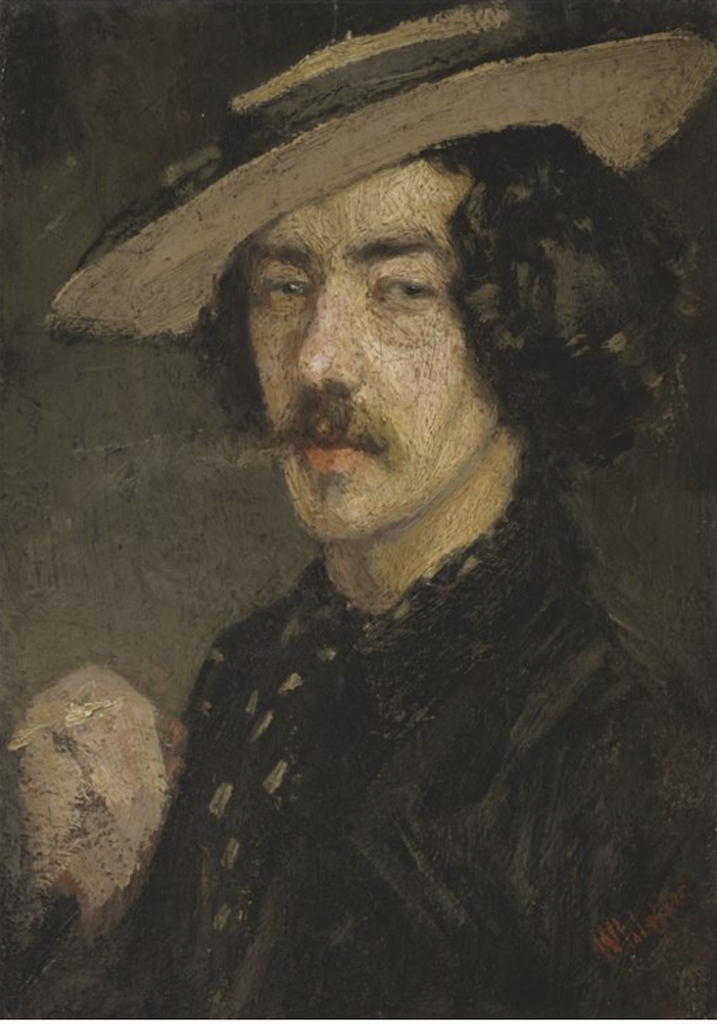

AI has shaken up the art world and has even struck fear in the hearts of artists, just as photography did when it was first presented to the public during the mid-19th century. French portrait painter Paul Delaroche summed up these fears upon seeing a daguerreotype in 1840 by reportedly saying, “From this day forward, painting is dead.”

Clearly, photography didn’t kill painting or even slow down its evolution from Impressionism to Dadaism to Abstract Expressionism and on to where we now see a resurgence in traditional Renaissance techniques in atelier-style schools across the country. Photography remains a useful tool for painters and sculptors, as well as a distinct artistic genre in its own right.

It's a Brave New...Something

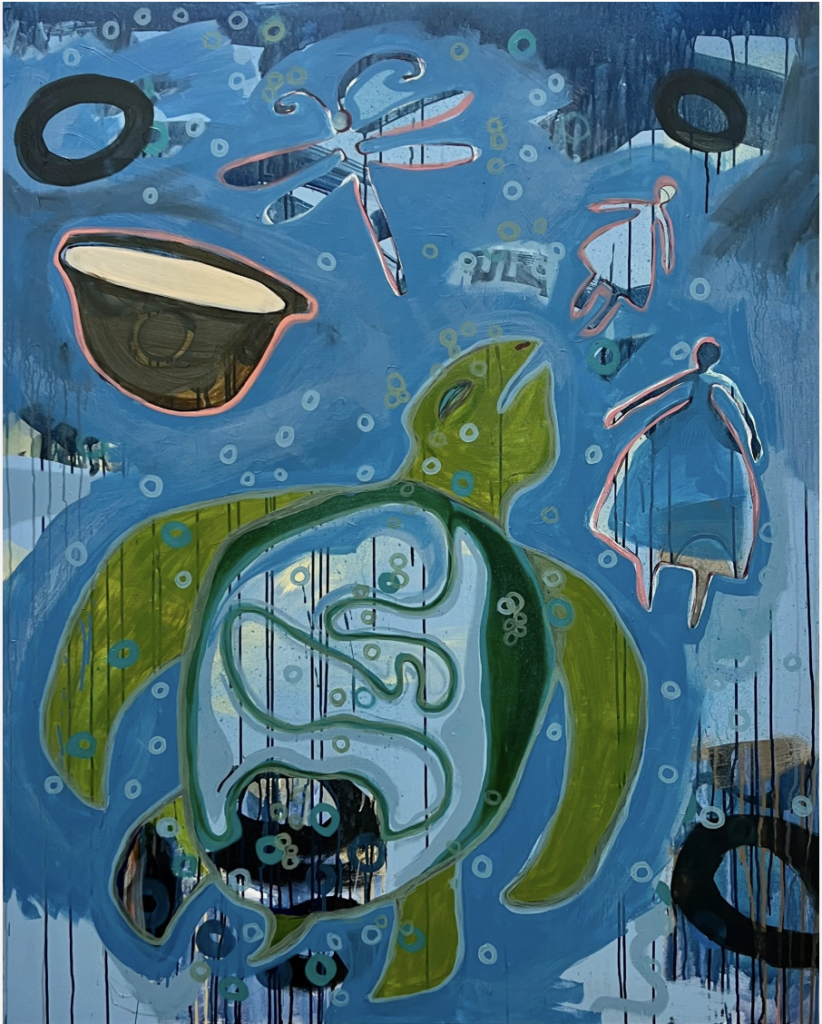

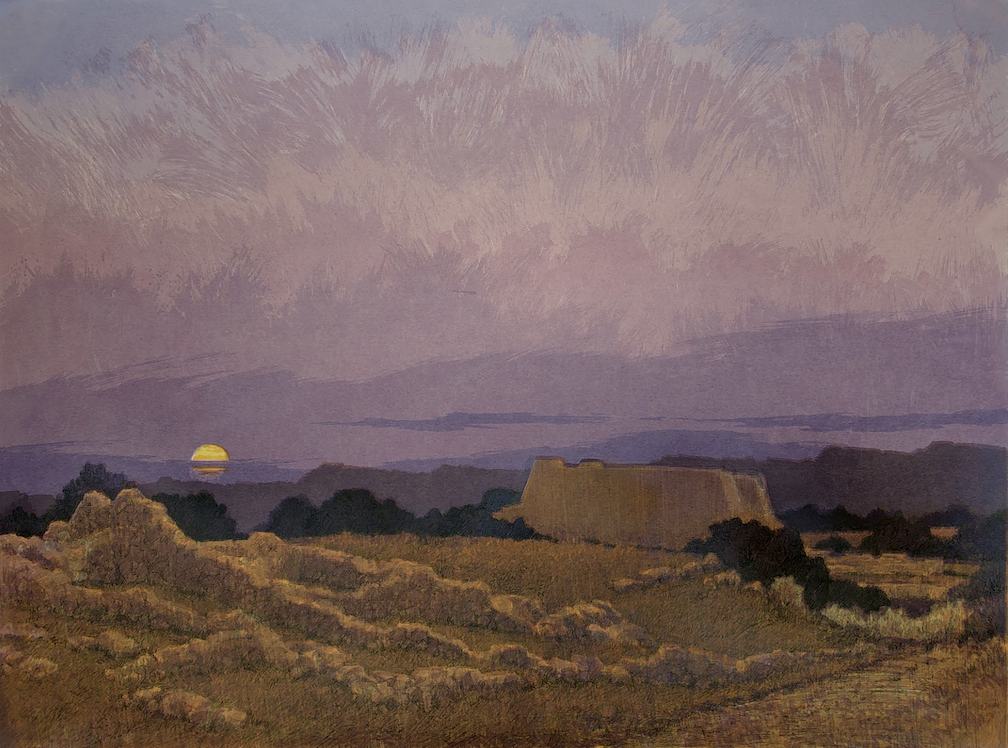

To understand how AI and other advanced technologies are changing art, Sarah Winkler, a contemporary landscape painter in Morrison, Colorado, shares her insights on navigating this brave new world.

“People are worried that AI will replace artists, but that’s not my take on it,” says Winkler, who doesn’t use AI to generate art or compositions but uses it for in-depth research. “I can have these deep, long conversations with it,” she says. “Because my paintings are the story of how a landscape was formed, I might ask AI about the geology of, say, White Sands National Park. Why do the dunes take on that shape? What kinds of rocks would I find there, and what is the nature of the place and the climate? I’m using AI for deeper information about place.”

Crossing the line

Winkler also uses AI to pull up examples of how other artists have portrayed similar landscapes to what she’s currently working on. “That’s important because I don’t want to duplicate someone else’s work,” Winkler says. “I basically use it to hone my research. I already know what I’m going to paint; I just need a little more information. AI will scour the internet in seconds and give me information sourced from books, articles, and teaching workshops that exist online. It literally shaves off hundreds of hours of research.”

Other technologies that artists have employed for decades include CorelDRAW and Photoshop, which can mimic traditional techniques or transform someone else’s art into a new creation. Winkler, who began in graphic design, witnessed how technology dramatically altered the demand for fine art illustrators. But she has also embraced these technologies in her own work, creating small-scale collages using paper and photographs as models for her larger paintings. “I can source copyright-free photos that AI finds and use them as a layer in my collage sketches with my own photos and textural elements,” she explains. “Then I scan those into Photoshop and rework the design until it’s where I can envision it as a painting.”

Where technology crosses a line is when an artist takes someone else’s photos or paintings found online, feeds them into Photoshop, and manipulates the image into a painting or giclee print, something that can also be easily achieved with generative AI. “The anxiety over generative AI is that someone could type in, ‘create a mountain scene like Sarah’s.’ Generative AI might come up with an image like mine that the person then manipulates in some small way. The issue is, who is the original creator in this world?”

Oh, for God's Sake

Jake Taplin’s video, “How AI Tricked the World’s Largest Painting Competition,” is a useful resource for distinguishing between generative AI art and original artwork. Taplin critiques an AI-generated creation, a painting titled “The Witchling,” that was a prize-winning entry in the Art Renewal Center (ARC) 2024 competition of Realist art.

Had the judges known what to look for, “The Witchling” would have easily been caught and disqualified early on. Only after it won awards was the obvious AI trickery called to their attention. The ARC revoked the prize; its rules clearly state that AI and computer-generated art are strictly prohibited.

Check out Taplin’s video to learn the key signs of AI-created art, which include “strange AI textures, drawing errors, and wonky lighting effects.” Of course, these tips will only be briefly relevant because as AI learns, it will soon be able to correct these errors.

Move Over Rodin-There's an App for That

Tom Bollinger, the owner for more than 20 years of Bollinger Atelier, a specialized art casting and fabrication studio in Tempe, Arizona, provides another perspective. He says that technology is not only responsible for changing the means of production, but it’s also responsible for a larger perceptual shift. “Our entire culture is now driven by speed,” Bollinger says. “When Amazon can deliver something to you in a day or two, it changes the mindset. In the old days, when most of our sculpture clients understood the process, we had plenty of time to work. A life-sized sculpture would take three to five months to be sculpted, and then the clay sculpture would proceed to mold-making, then casting. That’s radically changed.”

Sculptors have used technology for decades, which has helped lower the cost of casting art. “But 3D scanning and rapid prototyping,” Bollinger says, “that’s really sped things up.” This technology enables one to scan a person and send those digital files to a company that 3D prints a wax mold, which is then sent to a foundry for casting. The “artist” in this scenario never has to get his hands dirty.

But is it cheating to print a scan of a model and pass it off as an original work of art?

“This is maybe a morality question,” Bollinger says. “In the traditional sense, yes, I consider that cheating. But if the end-user doesn’t see it as cheating, if they don’t care how these sculptures were made, then it’s really a transactional relationship. A lot of times during the commissioning process, it’s not about the art; it’s about the likeness of the figure to historical photographs.”

Before 3D scans and printing, a traditional monumental sculpture could take two to three years to finish. Now, according to Bollinger, a life-sized sculpture can be scanned, printed, and delivered in six months. “You can skip the mold making, skip the wax making, skip the wax dressing, and go straight to gating and casting,” he says. “For traditionalists, this is almost heresy. But I think for our younger artists, they’re all in. A lot of people just send us 3D files, and we print and cast them.”

Taking Control of Technology

There is a hybrid approach that Bollinger sees artists adapting in their practice: A sculptor creates a smaller maquette to send through the rapid prototyping process and then reworks the rapid prototype with additional wax. “They then assemble the prototype and resculpt the figure to get the lifelike texture that we want to see,” Bollinger says.

Here’s where collectors need to examine the work they are considering and become familiar with the artists they are collecting. Rapid prototypes created from scans of a person won’t show the hand of the artist — tool marks, fingerprints, and surface texture — and scans of an artist’s maquette leave little opportunity for the artist to correct proportion errors. “That happens quite a bit when somebody’s modeling an 18-inch figure and then has it scanned to life-size; the head will be too big or too little, for example. It’s a matter of getting those proportions correct,” Bollinger explains.

In the above three images, you can see how sculptor Laurie Barton used a hybrid approach to complete her commission of Minerva for the National Museum of the Marine Corps. She began by sculpting a maquette then had a 3D scan done. The scan was used to create a large foam armature. She clayed the armature, which gave her the opportunity to correct any issues and add more detail. Finally, she had traditional molds made, which will be sent to her foundry to be cast in bronze.

The Hand of the Artist

Over the years, the art world has confronted forgers and cheats, all trying to make a fast buck by faking out collectors and curators. Technology — on both sides of the issue — has kept pace with the cheaters by offering scientific data used in validating authenticity and provenance, and uncovering fakery.

“I think everyone has a large digital footprint these days,” Winkler says. “Artists post a lot of their art online where AI can access imagery. This exacerbates the problems with copyright, especially for artists whose end products are in digital print formats that can be reproduced more easily without the artist’s direct involvement. In this instance, there’s not a lot of control over someone making their own rip-off of your work and then selling it. Collectors have to educate themselves about different art media, and that will get trickier as time goes on because AI-generated art exists in another realm that we can’t control.”

But knowing the downside, Winkler and Bollinger both see AI and technology as offering more opportunities for creating art. “A proper artist will know they can’t hit three buttons and get a painting,” Winkler says. “You have to use your voice. I also see artists cleverly finding ways to distance themselves from AI by changing their materials or surfaces to make sure there’s no question it was done by hand.”

“You always want to see the hand of the sculptor,” Bollinger adds. “You want to see tool marks and finger marks; that’s what gives a sculpture life.”