Traditionally, women artists have had to make a choice between career and motherhood. More women, however, are finding ways to have their cake and eat it too. Four dynamic career artists talk about how they dealt with the Mommy Problem.

When Adrienne Stein and her husband, artist Quang Ho, told a group of friends they were pregnant, one man—an artist they both knew well—turned to Adrienne and said, “You know your career is going to take a big hit.”

“I thought it was interesting,” Adrienne says, “that he decided to say that to me and not Quang. The insinuation being that I will be giving up my career to raise a child.”

A Tax On Pants

That artist’s comment aligns with hundreds of years of historical proof that women traditionally have given up whatever they were doing to raise children, which is probably why the women artists whose names most readily come to mind didn’t have kids.

But really, it’s not just motherhood that sidelines women. Here’s a fun fact. Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899) was required to get a permit to wear trousers, which she needed so she could attend horse fairs and study animals at slaughterhouses and draw on location or ride her own horse comfortably. Bonheur, who never married and didn’t have children, was, by the way, a financially independent artist—quite wealthy, by all accounts, from the sale of paintings—at a time when women who made art were looked on as having a nice hobby, something to keep idle hands busy while the family was off doing other things.

Then there’s Mary Cassatt (1844-1926) who never married or had children either. Some have speculated that childhood trauma precluded her from marrying. More likely, she realized she had to choose between motherhood and an artist’s life, and so chose artist.

Sure You Can Be An Artist and Have Kids

As abstract expressionism exploded across the US, a few women artists were making strong contributions, however, it was extremely rare to meet a female artist of the early and mid-twentieth century who had children. Of the famous Ninth Street women—Lee Krasner, Elain DeKooning, Helen Frankenthaler and others—only Grace Hartigan had a child and she sent him to be raised by her parents while she pursued her career.

In more recent times, there have been prominent women artists who raised children but for more women, Tracey Emin’s famous commentary rings true:

There are good artists that have children. Of course there are. They are called men.

To get a pulse on contemporary women artists who have or currently are negotiating careers and mothering, we gathered Adrienne Stein, Kate Brockman, Robin Cole, and Stephanie Hartshorn to discuss the Mommy Problem.

The Mommy Problem

“I had moments where I’d think: I have to get the hell out of here and get to the studio, even if I just sit and stare at an artwork for two hours,” sculptor Kate Brockman confesses, reflecting on her choice to ultimately put her career on the backburner for eighteen years while she raised her daughter. “It just felt so selfish to go to my studio.”

Adrienne Stein, despite well-meaning warnings, hasn’t broken her stride. “I had laid a foundation of showing in galleries and doing portrait commissions by the time I met my husband,” she said. “I had built my personal vision as an artist before becoming a parent.”

Stephanie Hartshorn was working as an architect when she married and started a family. The thought of shifting into an art career happened, in a way, because of her children and the desire to instill creativity in them.

“When my girls were born, I ended up staying home for six years—that was unplanned. It worked out beautifully and I would not take one of those days away,” she says. “It’s strange though. I know myself as these different iteration in life; my girls only know me as an artist, and I find that mind blowing.”

Keeping a Foot in the Door

“I think this is so personality specific,” says Robin Cole, as she takes in what her fellow artists are saying. “I mean, it took me a really long time to decide that I wanted to have children, at a philosophical level. So, when I found myself with this sweet baby boy, it took me by surprise how much I absolutely ceased to care about anything else. It’s shocking. I thought I’d be back out in the studio in eight weeks. I mean, I’m self-employed, right? I can take as much unpaid leave as I want, but I am a meaningful contributor to our family’s bottom line.”

It’s not just contributing to the bottom line, though; it’s keeping a foot in the door in a world where you are easily replaced.

“Liam has really lived in our studios ever since he was born,” Stein says. “And by that I mean at three days old he was strapped on me in my studio.” This is because she couldn’t take time off—she had shows lined up and paintings in various stages that needed to be completed and shipped across the country. “I’m very fortunate to have a wonderful and supportive partner who’s very participatory. And since we’re both artists, it worked for us to fold him right into what we were already doing.”

Don't Mind the Belly

Hartshorn recalls walking around construction sites days before going into labor. “My daughter was born a week after my last big project ended,” she recalls. “Kate was born and right away I knew that the allotted time off was not enough. I requested an extra three months without pay.”

Hartshorn did go back to work but by the time her second daughter came along, the economy had gone south, and architecture firms were closing. Hartshorn took the opportunity to regroup and focus on developing her painting career.

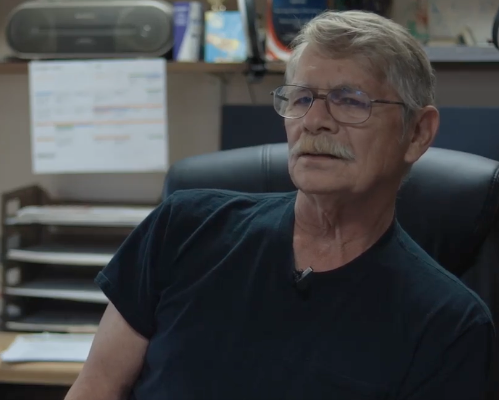

For Brockman, a bronze sculptor who, prior to marrying had built a foundry in her studio to pour her own bronze casts, there was no way she could have a child anywhere near her studio. The bigger problem was finding a solid stretch of time to work away from home. “I couldn’t just pick up a piece of clay and start sculpting,” she says. “You’ve got to make an armature and, well, there’s a process. So, unless I could get four hours in my studio, nothing was going to happen.”

Postpartum--It's Real, Y'all

“I was in a very, very strange emotional and psychological place in postpartum,” Cole recalls. “I could not be parted from that child for more than a couple of hours for at least a year. Now that he’s a toddler, I do feel better about being away from him. I still harbor truly a lot of guilt for not perfectly sculpting every single moment of his existence, but I think it’s probably for the best that I don’t.”

And lest we gloss over the fact that chasing children is just plain exhausting mentally and physically, Cole adds, “One thing I have learned about myself is the type of energy that the immense life force that is toddler-hood takes from me comes out of my creative energy. I just can’t work in the studio without childcare because I can never fully get into the mental space that I need to be in to do any kind of meaningful work.”

“There are times that we have deadlines,” Stein says. “We have to work on weekends and sometimes into the evenings after I put Liam to bed. I think Quang’s less stressed out than I am because he’s a lot more established. And he’s at a point in his life where he can enjoy being a dad.”

The Guilt Spiral

Mommy groups and PTO parents generally don’t understand what these women artists do, either. Really, why can’t you just crank out a painting while you’re making cookies?

“I loved being involved with the girls’ school, but I had a new path in art opening for me,” Hartshorn recalls. “And I had not fully established myself.” So began the guilt spiral. “When things were happening at the school,” she says, “I found myself thinking I could help but wait, this is my time and it’s a very short window before the kids get home and need me.”

But as hard as she worked at her art, she says she wasn’t really considered a career woman either; she was looked at instead as someone who had a self-centered hobby. “It was really stressful for me at times,” Hartshorn says. “I just felt so much guilt.”

Now that Brockman’s daughter is heading off to college, she finds the divide between friend groups quite striking. “I had some sculptures in a gallery show downtown. All my friends came, and they were like, Oh, this is serious stuff; you’re not just fooling around with a little bit of clay,” Brockman says. “But I will say that beyond the parenting group, I kind of feel like an outsider anyway, with anybody who is not an artist. I mean, I don’t think my husband gets what I do, really, or why I do it.”

Loosing Yourself

“I think it’s very easy to lose yourself,” Stein says, not only of motherhood but of being married to an established artist.

“I sometimes question whether I am sucked into Quang’s vortex already. But I was never Quang’s student, and I don’t paint anything like him. I’ve had a path that’s really distinct. I have my own unique vision and artistic approach. We influence each other a lot as artists, and we ask for each other’s opinions, and we critique each other’s work quite a bit. And Quang is devoted to me having as much time to paint and to develop as an artist as he gets.”

Cole admits she was worried about losing herself and her art because she had been, before marriage, fiercely independent. “The part that kind of surprised me the most,” Cole says, “was not external pressure. It was a very honest, internal yearning. I did not understand how much of my emotional register had not been explored yet. And there was so much that came into my being as a mother, and by extension as an artist, that I didn’t know I was missing.”

Rediscovering Yourself

“Being a mother,” Brockman adds, “has matured me in a way that allowed me to jump right back into making art. I’m not behind, I haven’t suffered; my skills are still there. But now I understand unconditional love. I understand some of the other elements that only parenting really could have given me.”

And despite the fact that juggling motherhood and career requires a tremendous strength and patience and an ability to navigate minefields, for an artist, Coles says, there’s an unparalleled richness that comes into your life. “Though it took quite a number of studio hours away from me,” she says, “it returned dividends. It added a sort of nuance and fearlessness to my creativity that maybe wasn’t there before.”

“Yes,” Adrienne says. “I would just piggyback on what Robin has said that when we think of ourselves as artists, the primary thing is the hours spent in the studio, right? Our craft. But the most important piece that we often don’t think about, which is far more important than the hours, is the depth of the well that the art springs forth from. And there’s just nothing richer than loving your child and experiencing parenthood. And the art and the inspiration that comes from it happens in ways that you don’t expect.”

It's All In How You Look at It

“It’s really important to think in terms not of what you might be losing but what you’re gaining,” Brockman says. “And you don’t know what that is until you’re holding that baby in your arms for the first time.” Her advice: Be open to allowing your life to change instead of dwelling on what you might miss. “I have lots of friends who have maintained very good studio practices as sculptors and parents” she says. “Everyone’s different and it’s a very personal thing. What might work for your friend might not work for you.”

“I’m going to propose,” Hartshorn says as we wrap up our conversation, “that it’s not the mommy problem; it’s the mommy puzzle. Problems have weight. A puzzle, though, we’ve got all the pieces in the box. It’s a matter of putting them together, and it takes time, but they’re all there.”

If you enjoy my blog, please subscribe and feel free to share with friends.

And, if you have an art topic you would like me to explore, leave a comment below!