The common thread of this exhibit was obvious, but the undercurrent of ideas, objectification, bias, and subjugation were not as readily apparent. I had the good fortune of interviewing these women and asking for their honest, unvarnished opinions. I am grateful for their time and trust. Some of the important issues that surfaced were around opportunity and issues with creating “Black” art versus simply being free to create Art.

What it looks like to us is: Here’s a black woman, come look at what it is to be a black woman in the arts.

One artist pointed out that there is a push to get black women into the public eye but, she said, “What it looks like to us is: Here’s a black woman, come look at what it is to be a black woman in the arts.” She went on to express her frustration that everyone wants black woman to talk about what it feels like to be a black but that this question undermines their effort, knowledge and artistic expression by putting them in a box. Having the conversation is valid but if that’s the only conversation available to women of color, it’s a bad one to be stuck in. I couldn’t agree more.

So, while calling attention to artists of color is good, it’s not enough. We need to change the conversation, but we also need to realize that if artists’ personal circumstances don’t change, all the opportunities in the world won’t matter. The reality is that many women simply can’t afford to accept a grant, residency or exhibition and buy groceries, pay the rent, get their kids to school. But, as several artists stated, we remain positive; it’s the only way to keep moving forward.

-Rose Fredrick, January 2020

Autumn Thomas

My work in the studio reflects the way I try to approach life: with a combination of structure and fluidity. My artwork consists of bending solid structures into curved forms. I sit with a straight piece of wood for several hours, measuring out precise lines for cuts; most of my work has 75 to100 single lines. Then I cut through the wood at each measured line. Each cut is representative of having been ‘cut-down’ by—or negatively affected by—racism, sexism, classism, heterosexism and the perception that a short, black woman must be angry and contentious, dependent and thus incapable of intelligence. Each of these calculated, repetitive cuts allows the wood to bend and thus represents the many forms in which the constant bias I face does not break me, but instead teaches me to maneuver life with more fluidity.

Each cut is representative of having been ‘cut-down’ by—or negatively affected by—racism, sexism, classism, heterosexism and the perception that a short, black woman must be angry and contentious, dependent and thus incapable of intelligence.

My work is about the fluidity of structure. Structure can be literal, like something made of wood that is sound and stable, like a house. But structure can also be figurative and theoretical, like the structures of racism and sexism. It is within those structures that the majority of our ideals—and the focus of my work—are embedded. They are institutions in which we live and reference the progress of our lives, even as we try to remove ourselves from them, they remain our frames of reference, for better or for worse.

The long-term goal of my work is to affect the way we navigate these institutions and structures by forcing a change in visual perspective. Our perceptions of others are continually influenced by external sources that we consciously and subconsciously consume – they are flooded with truths and untruths. We are also innately affected by a term called inattentional blindness. This happens when we focus solely on one aspect of something, i.e. the color of a person’s skin, and we miss the nuances of that person and the value they add to a community. I believe that by presenting something in an unexpected form, whether it is a curved piece of wood or a black woman that is both abstract and multidimensional, I and other like-minded artists can affect the degree to which we ‘see’ each other more wholly.

My inspirations are Wangetchi Mutu and James Baldwin. Baldwin’s writings push me to consider the intricacies of having multiple minority statuses. Mutu—I find her work to be transcendental and embedded with energy. I want to be able to share that feeling in my own work as well.

Ella Maria Ray

I am committed to decolonizing thought, preventing erasure—insisting on not being erased—and having a voice. I’m a part of a generation of people on the cusp: people who remember typewriters, using an abacus, and a segregated Denver. I am, unapologetically, who I am and I’m going to use the privilege I have to make my contribution through the experience and lens of people of color.

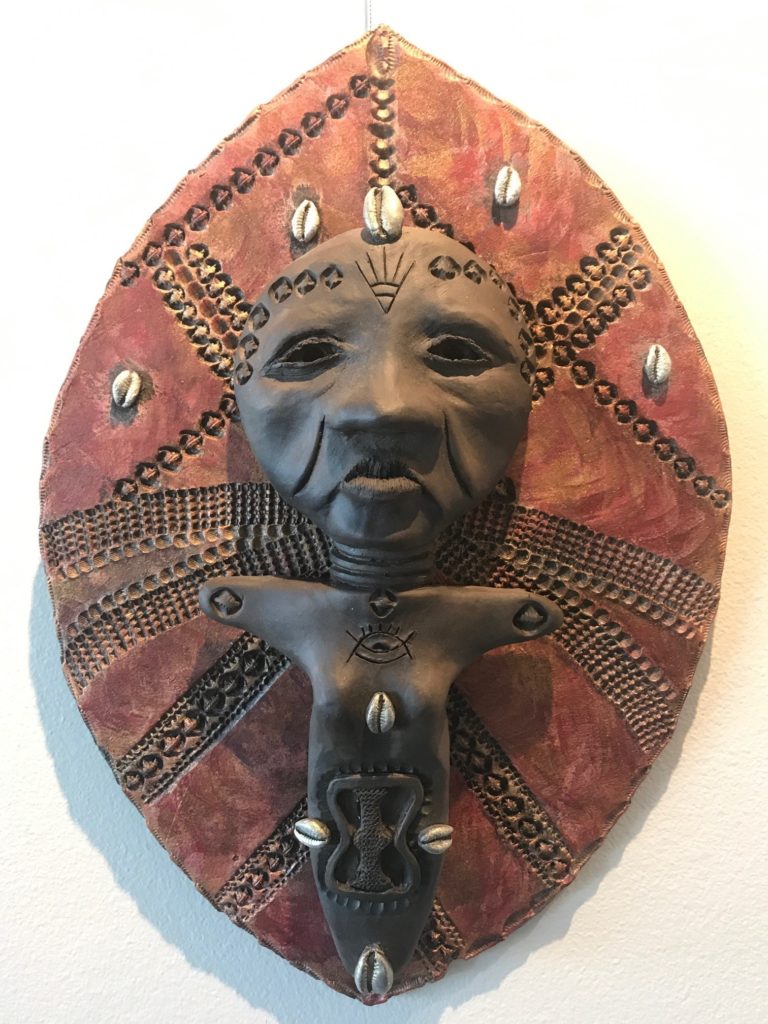

Part of what I’m grappling with is dismantling ideas about “Africanity” and “Blackness.” As a visual artist, I am looking at the differences between continental Africans and diasporic Africans. Clay has worked as a wonderful portal to do that. I see my sculpture as a kind of handwriting, a visual text. Every piece I create is embedded with meaning. Clay is my paper. Clay is the text in which I read.

Part of what I’m grappling with is dismantling ideas about “Africanity” and “Blackness.”

I am often inspired by the works of black women writers. Octavia Butler is my primary muse because she insisted on being heard. She insisted on staying true to her art form as a writer. In her novels, fact and fiction come together to give us her particular kind of speculative fiction. That’s what I’m doing as an anthropological artist: I am seeing art as a powerful art form to say what I have to say.

I am drawn to and engaged in exploring the power of black women’s lives. I do think it is an on-going challenge to be heard and not “other-ized.” We have a society that is shaped by caricature and stereotype. I believe, to be a black woman artist is a divine calling. But it goes against the grain of how success is defined, if you put your art at the center of your life, you are truly walking on the wild side.

In my work, there is significance and importance in the cowry shells and Adinkra symbols, West African imagery, Akua figure. The Adinkra stand as symbols for my own life. My mask making is a mystical way of concealing and reveling at the same time. As a diasporic, I am used to concealing my nature when in the mainstream, but there is also the desire to be authentic.

I love talking about the process because that is metaphorical, embedded with meaning. I love when my work evokes an emotion. In the tradition of African American storytelling, it is a call and viewers give me a response.

In the tradition of African American storytelling, it is a call and viewers give me a response.

I am who I am because of the committed work of my mother who was very much about constructing a kind of curriculum for living. I grew up in a house were crafts were crucial and important. That was the foundation from which my visual knowledge emerged. I am a performance artist: I was a violinist then a storyteller. I come to clay by way of other avenues but have found that clay is my aesthetic and spiritual home.

Tya Anthony

I relocated to Denver in 2011 from Baltimore to pursue art as catharsis and career, attempting to connect the dots of my own chameleon identity. Born in Colorado Springs in the 1970s, then traveling the globe with my military family throughout the 80s, I felt a strong sensation to return to the West at this juncture of my life. I found Denver to be a place of grounding in my work; Denver has personality and spiritually. My work reflects the West by way of rustic, analog mediums and alternative practices focused on aligning memories into narratives on a national level. I explore identity from all angles including imagination.

Being a woman of color in the arts is absolutely life-giving, on one hand, and equally complicated on the other.

Being a woman of color in the arts is absolutely life-giving, on one hand, and equally complicated on the other. However, being a woman in the arts today provides space for exploring this complex identity in ways unlike the past. More and more collaborative efforts are forming globally to support the evolution of what it means to be a practicing woman artist while creating more opportunities to share our theories, thoughts, and work.

Race has always played a role in my work whether through subject matter or thematically in exhibition. I hope this will become a trend of the past that inspires the expansion of when, where, and how black artists are exhibited, interviewed and highlighted. I belong to a collective called Pink Progression. We are over 100 artists in number focusing on the #MeToo movement. Annually, we work to bring awareness around Denver through exhibitions based on collaborations that bring this message to the forefront. I’ve reached deeply into the “Divine Feminine” and look forward to the opportunity to create more collaborative series of work.

My inspirations are Wangechi Mutu, Kara Walker, bell hooks, Irving Penn, and Richard Avedon. What motivates me to create is the ability to share meaningful conversations in order to affect positive change in the world.

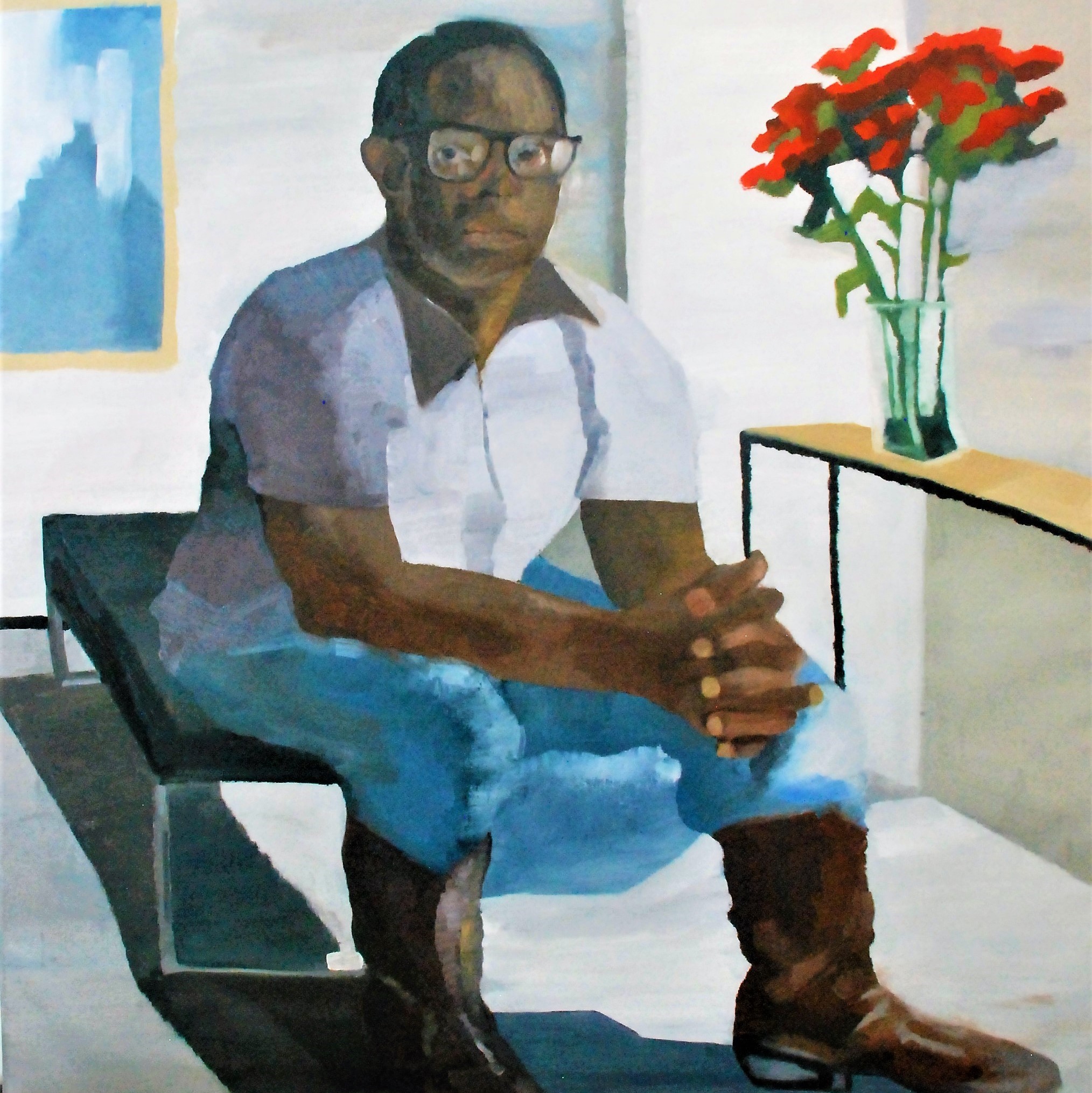

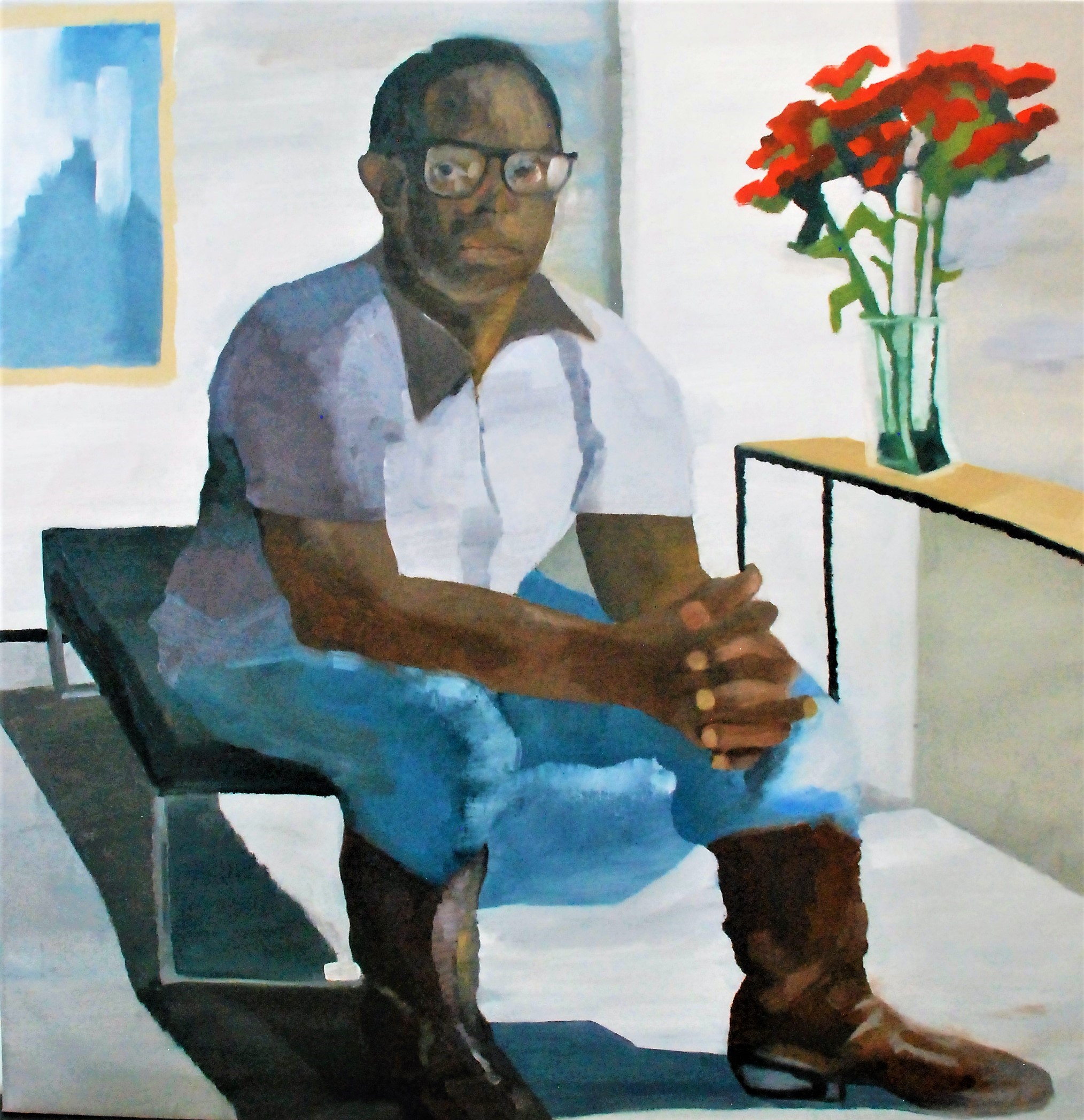

Rochelle Johnson

Identity is important to me because it speaks of what I know and have lived. I grew up in the late 70s and early 80s in a predominantly black neighborhood in Park Hill—that’s what I know. I’m a positive person; I try to present the positive because that’s what I experienced even though, on my TV, when I was growing up a lot of times black men were portrayed as a negative image.

There was a bookstore where I lived, Hue-Man Bookstore, run by black men. That’s where I ran into a book about Harlem Renaissance artists Jacob Lawrence and Lois M. Jones. These artists inspired me to want to paint, actually do this as a profession. I grew up in the church and I feel painting is my prayer to God. I try to pray every day.

I grew up in the church and I feel painting is my prayer to God. I try to pray every day.

I graduated from Rocky Mountain College of Art and Design. My prime focus was the black narrative but even in art school when I had my portfolio critiqued and later when was looking for work in advertising, I was told I had to paint white people, or I wouldn’t get work. I was shocked. I did work freelance but finally decided to go into fine art so I could do what I wanted and not rely on what the industry wanted me to do. What I wanted was to tell my stories.

The majority of my work focuses on the black narrative but I’m not talking about a shooting or black people being under siege. I’m reflecting how I think society should be and I think the norm should be inclusive of everybody.

For the portrait, “When Will They See Us?”, I did a sketch at the Art Students League, but the reference was of a model who was white. Back in my studio, I turned her into a black woman. I don’t know where the inspiration came from, I just didn’t like where the painting was going. I think the nose was where it started, it was too structural. So, I changed the nose and once I did that, it all came together.

It’s hard being an artist. Period. But being marginalized as a black artist…

You can imagine the deficit that black women have when it comes to gallery representation—there’s no space for us. It’s hard being an artist. Period. But being marginalized as a black artist…I think people put you in a category. People putting you in a box is never good. Some of it I get from other artist when I show them my work. It’s always kind of like, “Why are you painting white people? You should solely talk about the black experience.” That’s why I started painting people blue. If I painted them blue, it didn’t matter if they were Asian or white or Latino. It made a statement: We’re humans, it doesn’t matter what skin color you are.

Brigitte Thompson

My art is a perpetual exploration of my own identity. My art is first and foremost a form of self-care and therapy. It allows me to process and make real the emotions that plague me. When it comes to my identity as an artist born and raised in Colorado, I think it’s heavily reflected in the narrative and theme of my many of my series related works. My Father Can You Hear Me series was heavily influenced by identity as a black female in the Western US. This series not only explored identity on a local state level, but also explored it on a national, if not global level, by exploring the facets of my identity that were constructed by the religious and patriarchal meta narratives that govern us all.

My art is a perpetual exploration of my own identity.

In my own experience, I would honestly say that yes, there are many opportunities for women in the arts. However, as a black woman, these opportunities may be limited depending on what your primary focus is for your art. If you tend to focus on your identity or anything pertaining to your cultural heritage, you run the risk of being pigeonholed, disregarded, and possibly looked down upon by certain sects of the arts community. With that said, I do think being a woman of color in the arts in modern day America is largely a positive as it can allow one to stand out amongst other artists in a highly competitive field.

If you tend to focus on your identity or anything pertaining to your cultural heritage, you run the risk of being pigeonholed, disregarded, and possibly looked down upon by certain sects of the arts community.

I have seen more artists willing to speak up more about sexual predators in the art world and have seen some of my fellow female artists explore the topic of sexual trauma more in their work.

I confront gender bias quite a bit when showing my work. I sometimes get surprised looks and responses from people when I tell them that I did indeed create my work, as if it’s surprising that a woman, no less a black woman could paint the way I do.

People have responded in all sorts of ways to my work. From awe to annoyance, people’s responses have run the gambit. I feel like my work is generally well received, but I have definitely received negative responses. For one, I feel that people interpret as much depth from digital work as they do my traditional work, and some have said that my traditional work is far too serious and unrefined.

I have many inspirations, and they vary widely. Kehinde Wiley and Margaret Bowland (though problematic) have been huge influences of mine in the past year. I am also heavily inspired by the people around me. There are numerous local artists that have deeply inspired me to create and ultimately, become a better artist.

What inspires me? Everything, really. The moon, the stars, my life, other artists. The largest motivating factor behind my art right now is color. I am currently on the path to explore colors and the many ways in which they can be mixed together to create dimension and reality beyond themselves.