Over the years, curating the Coors Show and other exhibitions, my sense of this job has evolved in many ways except one: A curator is not an art director.

In other words, I do not tell artists what or how to create. If I wanted to make art, I would. But I don’t because it’s flippin’ hard to do.

I do like Hans-Ulrich Obrist’s notion of a modern curator, though:

“I see a curator as a catalyst, generator and motivator — a sparring partner, accompanying the artist while they build a show, and a bridge builder, creating a bridge to the public.”

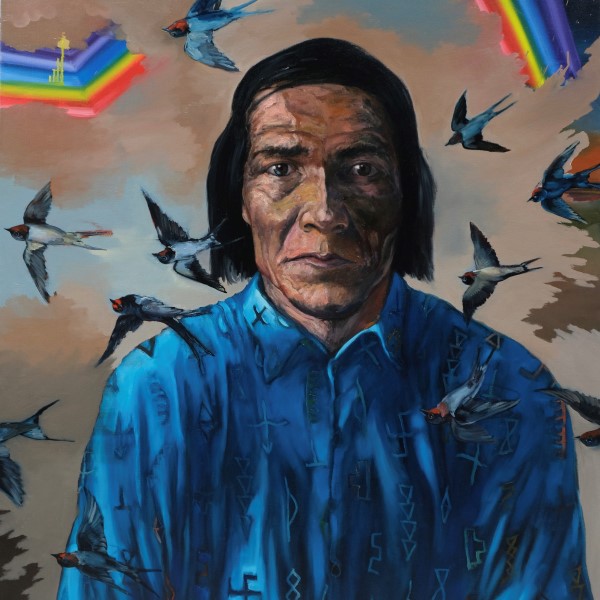

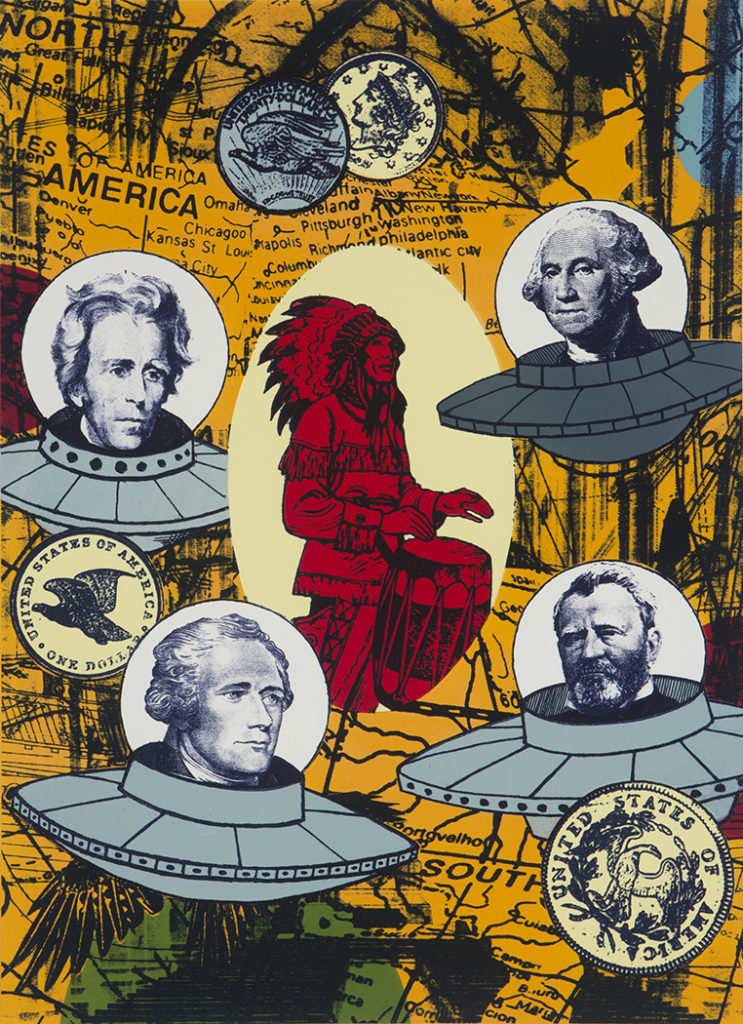

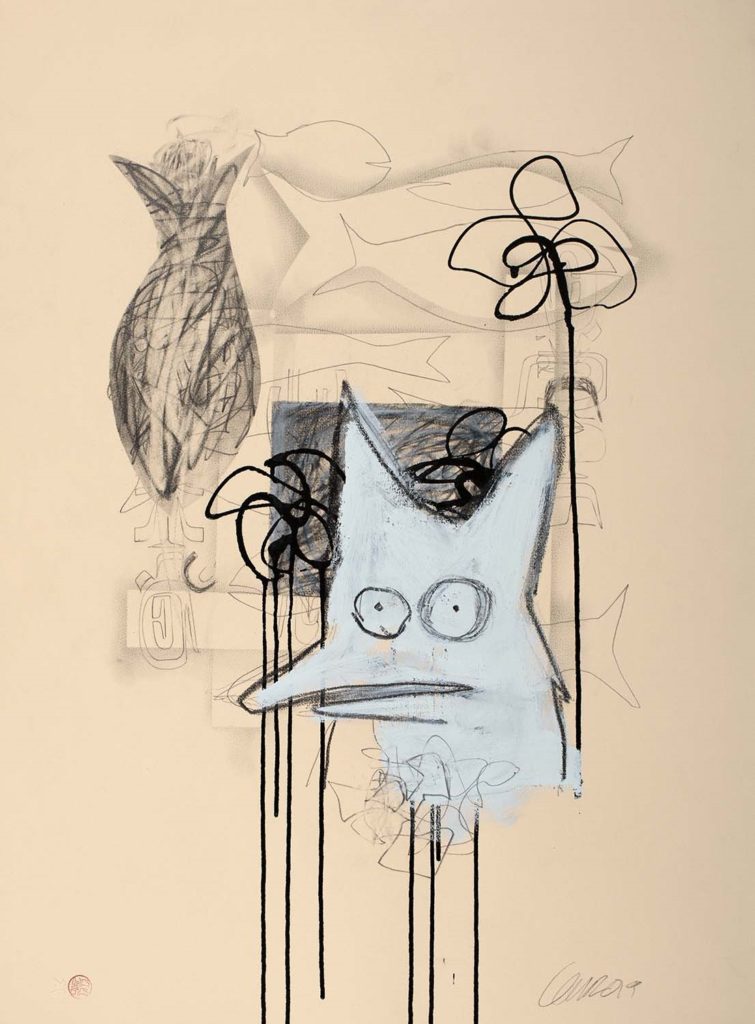

Meet David Griffin, 2022 Coors Show Featured Artist

Because so many people ask about my job–often believing it’s one long series of cocktail parties punctuated by studio visits where we talk art theory and drink cocktails until the wee hours (not far from the truth, actually)–I thought I’d share a conversation not unlike others I often have with artists. This call with David Griffin was to discuss what he was planning for the next Coors Show.

My first concern was making sure he wasn’t trying to “psych-out” our audience. i.e., creating paintings he thought people would like vs. painting that were authentically of his “voice.”

To which David replied:

“Over thinking this thing is exactly where I was headed. Complicating it, adding all these underlying meanings, which I don’t even know the answer to so how could I expect someone else to know the answer? I have to continue to remind myself–because this is like the Super Bowl to me–I have to treat it like it’s just another game.”

I knew it. Once I assuaged David’s pre-game jitters, we began talking about his journey from illustrator to fine artist.

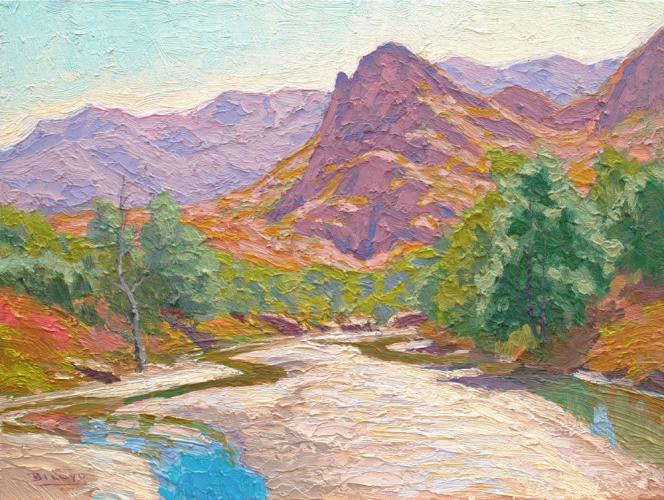

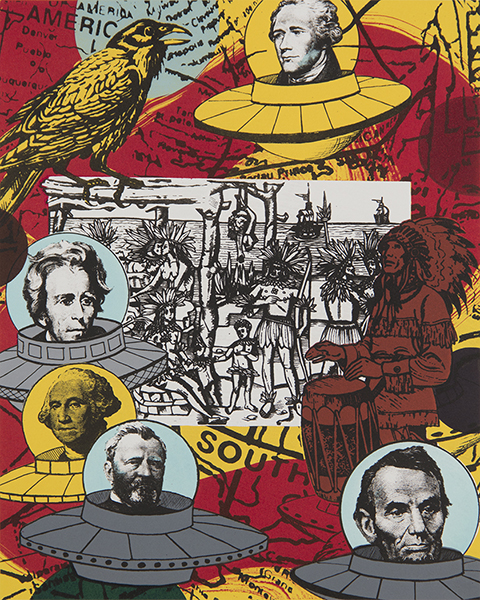

ROSE: When you started with the show, you were painting cowboys. And you had been an illustrator. But your work has evolved so much; I haven’t seen you paint a cowboy in five, six years.

DAVID: Something happened. Maybe it was a step at a time but there was–I’m going to use the word liberty–maybe it was permission, but liberty to do what I wanted to do not what I thought people expect me to do. You were encouraging for all of us to do what we feel. And that started a whole other conversation of digging deeper into why I was doing what I was doing in the first place. If I was going to understand how to talk to people, I needed to understand what was going on in my head about these paintings.

R: How did you do that?

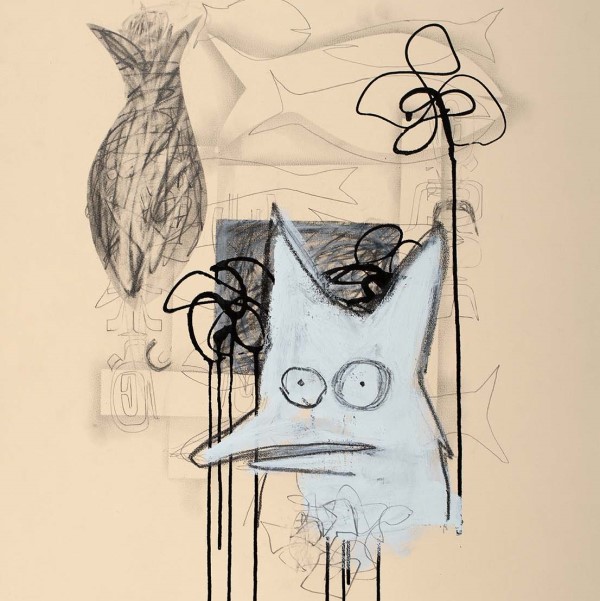

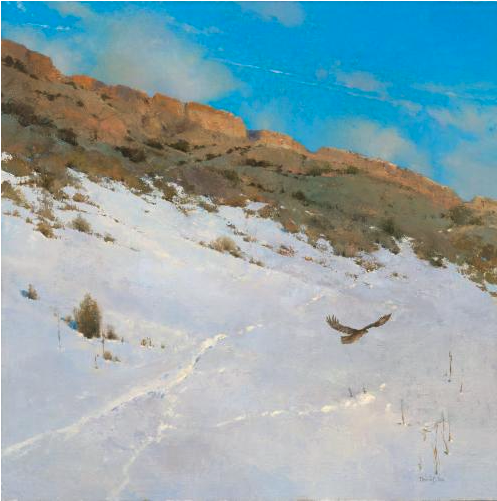

D: Well, I don’t know. That’s what’s been amazing about this journey. I felt like these newest paintings just happened. And it’s not that easy, you don’t see the struggle. You don’t see the battle, the blood, and sweat. But, I think, I connected to creation, to nature, in a way that I was already probably connected and just didn’t know it.

I was listening to an interview with Andrew Wyeth the other day. He was talking about why he did what he did, the impetus of his work, and he said, a lot of it comes from memory. So, that kind of affirmed what I was already thinking.

Now, I wouldn’t have taken a risk if I hadn’t already felt comfortable bringing it in the show. I could step out of something that was comfortable and into something that was maybe a little uncomfortable and think, well, I know Rose is going to tell me what she thinks and that’s what I really wanted to know.

R: When you made the switch from illustration, I think that had to be a conscious decision, right? Tell me about that because when you first started with the show, you were painting “fine illustration.” And now you have completely switched. But it was gradual.

D: I agree. When illustrators switch to fine art it is a real departure financially because you would get a job from Sports Illustrated and get ten-grand for a cover, five-grand minimum.

All of the sudden, you go to a gallery and start asking ten-grand for a painting right off the bat and collectors are thinking, wait a minute, I don’t know who you are.

My transition was a little less dramatic than that. I’d been to Europe and I’d started to paint some things, figuratives, and Tony Altermann came into my studio and said, ‘you know I can sell these paintings.’

So, he took three or four and sold them. That helped me make up my mind because I was trying to support my family at the time. My break was pretty clean. One day I was doing illustration, the next I was painting. It was that cut-and-dried.

I think the fact was, this was what I wanted to do all along. I got tired of being somebody’s hands. Deadlines and working all night. An art director would just send me a script and I’d have to turn it out. It’s a factory. I wanted more time to spend on painting.

R: And then Tony Altermann walked into your studio and gave you the opportunity to do your own thing–

D: Well, I did a lot of portraits for them, things I didn’t really care to do but it was a way to make a living. I stayed with him for a long time then one day he called and said, “you need to do something new. You can come and get these paintings.”

R: Wait, what happened?

D: I can’t remember, there was a financial turn down, I think, but there were times when the relationship was a little testy before that. Anyway, I walked down the alley to the gallery and got my paintings and didn’t talk to him again for a long time. That was a “rip the band-aid off” moment; I didn’t have anyone who was representing me then.

I was really in the salt mines. Then I got connected with Bill Bufford. He was bigger than life, he told you what to say and what to do. I’d pull up to the gallery and he’d be talking loud enough so you could hear him in the parking lot.

But, all those moments when I thought I was wandering in the desert, three kids at home, and then something would happen. Like getting a call from you about the Coors Show. I was in shock. I look back on landmarks and that was a huge landmark. I had given up illustration long before, of course, but that was a step that put me on a different path because, always before, gallery people had told me what to do.

R: That’s what I’m wondering about because, essentially, you traded an illustration rep for a different kind of illustration rep–the gallerist who dictated what you were to paint, right?

D: Yeah. I remember going to lunch with Tony, and he’d get a napkin on the table from where we were having lunch. I never had to ask him what he wanted me to do. Basically, it was: ‘Here’s the script and I’m going to give you the outline, metaphorically, David, and I’m going to tell you what to do.’ Bill wasn’t quite that dramatic about it but he’d still say, ‘David, you need to do more of this, this is what we can sell, and I don’t want to surprise my clients and spend a lot of time explaining what you’re doing.’

So, you’re right. I was a private, showing up, saluting, doing the paintings. When you came along, I kind of wanted you to tell me what to do.

R: Usually the first thing I tell artists when they come to the show is that I hired you to do what you do. I don’t paint for a very specific reason. I won’t tell you what to paint but I will tell you what I don’t think we can sell. But other than that, I’m never going to tell you what to do.

D: That was part of our first conversation and it was a little disconcerting from the standpoint of, “you mean I’ve got to come up with the ideas? You’re not going to tell me what to do?” I may have, in fact, asked you on more than one occasion, will this be OK? Because I was so uncomfortable. I’d been living in my head with something that I’d always been told: This is what you have to do to be successful. And then I find out, no, that’s not true. There’s another way to do this and a better way, a much more liberating way, creatively inspiring way to do this.

Not having anyone directing me, telling me what to do–believe it or not, Rose, that’s hard.

I look back on that now, and it was kind of a crutch and one of those things that was holding me back. I would take paintings to the gallery and they would say, “yeah, this one is working but take these back and give us more of these.” I was in the marketplace and selling but without complete freedom.

To be honest with you, when you’re given the freedom to do your own thing, it exposes your weaknesses. I could draw, I could paint, I knew color, but now I had to come up with my own ideas, and had to ask myself if I was up for the task. So, it did expose weaknesses. But they needed to be exposed. I needed to look at my weaknesses and my failures if I was going to do anything.

R: Freedom is, to an extent, scary. But if you trade one set of handcuffs–the art director for the overbearing art dealer telling you what to paint–what kind of life is that?

D: But you’re not growing. Think of all the people who had to have this conversation with themselves and their families about walking away from steady revenue. And I don’t regret Bufford or those guys telling me what to do; that was part of my training. But some of these artists painting western illustrations now have collectors calling and saying, ‘What are you working on?’ and ‘You better sell it so we don’t lose money on our investment.’ It’s hard enough coming up with the ideas and painting without having that pressure.

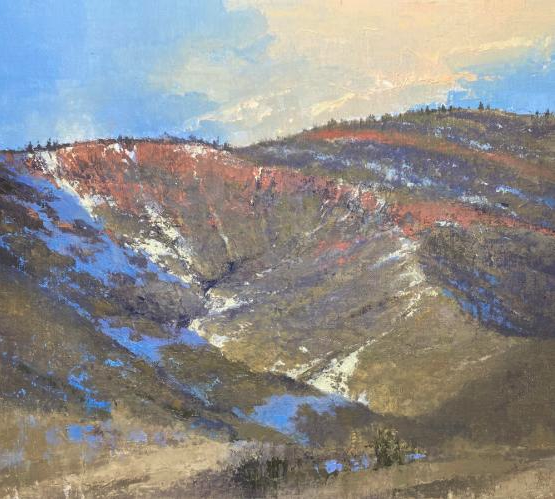

R: We were talking about that transition in your work, and I was saying on the phone to you, I think this work was a leap even from last year’s work. How did you make this leap?

D: I started to depend on a different part of me for the creative making. This year was the first time it was 100% me, not being influenced, either way, good or bad, by someone else. I think it had something to do with me having more confidence in my own intuition. I wanted the paintings to leave the studio because I was happy with them on my own terms, not because I thought somebody was going to like them.

R: How scary is it to create work that’s 100% you?

D: In my own experience, it’s real scary. But you’ve nurtured the ground I’m going into to the point where I’m able to grow my own voice. I hear that a lot, but I do think there is something to the point where you say, “this is what I like hearing coming out of my own voice,” metaphorically, and to have people respond. But it is scary because you just don’t know. We all want people to like us. The extension of that is, if people like my work, they like me. That’s dangerous and that’s scary because you’ve exposed yourself even more.

I’m sure artists have told you, at the Coors Show, “I feel like I’m standing there without any clothes on and I’m trying to tell you what’s important to me. And if you don’t like that, is it because you don’t like me?” That’s a bad way to put value on things. But risk and reward. The reward is bigger.

R: You were talking about deeper meaning, especially in landscape–

D: I’ve been reading the philosopher, Roger Scruton, and his conversations about how we live with beauty in the world we live in today, how we live with beautiful writing, beautiful film, beautiful paintings, and that in itself is how you describe beauty.

And I’d read Andrew Wyeth and Makoto Fujimura who talk about the theology of making and beauty. I would equate some of that to my thinking deeper about a painting. Now I sit and look at a painting longer, and wonder what does this say to me or do I need to start over? But it all comes back to: what’s beautiful and can I use that as a threshold?

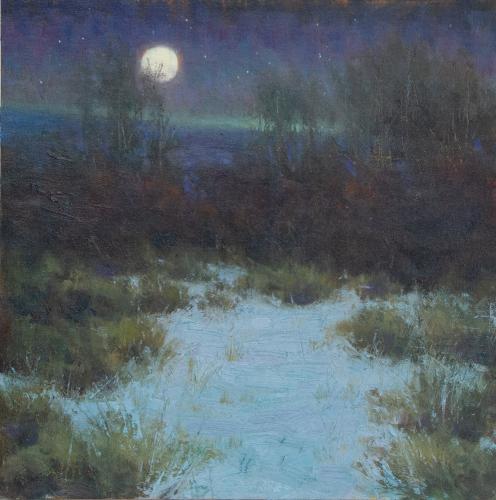

R: Several years ago, a PhD candidate in music reached out to you saying she would like to compose music for your painting, “Weathered Moon,” and would it be OK if she did so. You sent her the painting, and when she’d finished her thesis, she returned the painting along with a recording of the music created and composed for quartet (oboe, cello, bass, and violin). Tell me about that experience.

D: That was the first time I thought there was more to my paintings, that someone would get more out of my paintings, something more than a visual experience. Her thesis, it’s all these sounds you might hear when you’re out painting plein air, little discordant sounds that might be bugs over here, or the wind blowing through trees. And there’s a melody to it that was hard to find at first.

She was drawing sound out of a two dimensional painting. That was when I started focusing on landscape paintings.

R: We all worry about what others will think about our work. But, if we stop worrying and just let the work go out in the world, someone might just come along and create a symphony around it.

D: Yes. And, the collaborative effect is amazing. I do like collaboration. I think there is a value in that. You’re adding to the beauty; it’s a more beautiful orchestra.

R: Speaking of collaboration, after all these years moving from illustrator to another kind of illustrator but for galleries, to creating work for the Coors Show, do you still consider this stage a collaboration?

D: I would call it a collaboration. You have created an atmosphere that an artist can walk in and be part of. You’ve got people who love art. You’ve got people who are certainly well educated, they are well read, they understand what beauty is, they understand the value of that. And you have this show where you afford people the space to have conversations. I think every bit of it is collaborative.

You know, every year I walk around the show and tell my wife, “She painted the wall just for me. My paintings went on that wall perfectly. I know she did that just for me. I’m the only one she’s done this for, I’m sure of it.” Then I go walking around and see you’ve done this for everybody.

I’ve heard you talk about the joy of uncrating the paintings, taking them out, putting them on the wall, figuring how they go together, how they look when you come in or go out of the gallery, what the color is, the spacing, getting the lights all perfect. I don’t know what a job description of a curator is but I can’t imagine it’s more than what you do.

So the collaboration–you give me confidence because you’re confident and because as you describe, you’re an eternal optimist. People gravitate to who they want to be around. So, I do think the collaboration goes beyond that night.

R: On a personal note, with your Coors Show paintings this year, you tapped into a memory of mine, unwittingly. It was that painting, Thunderstruck. From the moment I saw it, my mind drifted back in time to my childhood, watching a storm roll in, feeling the air change and become charged with electricity, and that scent of petrichor.

D: Memories are strong. They might be the biggest impetus for a painting. I’m not going to dismiss those memories in my work. I’m going to hone in and make that the foundation. You’ve just given me more than you think you have. One day I’m really going to be able to tell you how grateful I am for all of this. You have single handedly been the most important part of my painting life.

R: I hope you know you make me look pretty darn good.

D: We’re gonna keep talking. But right now., I’m going out to take a walk and digest all this.

Recorded Zoom interview with the 2022 Coors Show Featured Artist, David Griffin, on February 9, 2021, has been edited it for clarity and brevity.

If you are interested in delving deeper, here’s a talk with Makoto Fujimura, on art and faith. Recorded on January 11, 2021, he talks about dealing with trauma and tragedy, and the connection to healing fractures through art.