A friend of mine asked if I taught luddite artists how to market your art online. He isn’t really anti-technology but is frustrated. I don’t blame him. The reality is that selling and promoting art online is frustrating because there are so many options from social media to websites to emails. Even more annoying: the technology behind those options is constantly changing.

Social Media & Art Sales

When it comes to marketing your art online, social media seems like the obvious choice. It’s free and can be a fun way to check out what your fellow artists are up to. But it’s a love-hate thing. Social media is a time suck and, more often than not, doesn’t result in sales. And yet, we all–myself included–keep posting.

Here’s the thing, as annoying as it is, I would never tell you to stop posting on social media. Far from it. In fact, you should definitely keep up with it (maybe set a timer so you get off at a reasonable hour) but keep at it because it is helping. It’s just not helping market your art online like you think it should.

Why Social Media Isn't Your Best Selling Tool

I know some art does sell through social media posts, but I’ve never heard of anyone selling there exclusively and consistently. If you are, I’d love to hear from you!

So, why doesn’t social media work? It’s pretty simply, really.

People who randomly give your post a “like” as they infinitely scroll aren’t engaged enough with your work to make a buying decision.

How Do You Turn Browsers into Buyers?

You see, there’s a missing link between scrolling and buying.

So, you may be wondering, how do you turn “likes” into sales?

Excellent question.

Answer: get scrollers to visit your website and sign up for your newsletter or emails.

Research shows that if a visitor to your website gives you their email, the chances of them becoming a buying client jump dramatically.

In a March 2023, Snov.io. com, reported that email marketing acquired 40 times more customers than Facebook and Twitter combined with the average click through rates for each channel:

– email marketing (3.57%)

– Facebook (0.07%)

– Twitter (0.03%)

How to Grow Your Email List

The majority of professional marketers believe email is more than twice as effective at generating leads than paid social media. Twice!

In order to effectively market your art online, you need to grow an email list of clients. There are some really important ways to do this.

- Have a sign up form on your website’s footer and contact page.

- Ask people to sign up at strategic places throughout your website.

- Give visitors to your website a compelling reason to sign up.

Compelling Reason #1: Send Awesome Newsletters

People who give you their email address actually are interested in you and your work. They want to hear from you and may already be contemplating buying something from you. They are your perfect clients and your target audience.

When it comes to marketing your art online and making sales, your email list holds the greatest opportunity.

This is why I want you to create effective newsletters (and compelling blogs–I’ll explain next).

How to Create Awesome Newsletters

Newsletters I receive from artists tend to be focused on sales and promoting the latest painting or awards, workshop schedules, etc. This seems like the obvious reason for a newsletter, right? It is a “news” letter, after all.

But you’re missing your greatest opportunity to really engage your audience and bring them into your world.

If you get anything out of this blog, it should be this:

Follow the 80/20 rule: give, give, give away insights and knowledge 80% of the time; ask for something only 20%.

The Secret to Email Success: Change the Conversation

Here’s a simple fix for newsletters that are always asking for something or sound like bragging. Turn the announcement of a new painting into a conversation about what inspired that painting or, as the case may be, series of paintings (photos, sculptures, etc.).

EXAMPLE

STANDARD EMAIL: “Hey, I just finished a new painting in my zen series. Here’s a link.”

CONVERT TO: “I’ve been searching for ways to find peace in my life. As many of you know, I have recently gone through challenging times. This new work started to flow after I took time off to hike and camp out in the desert where I could be in total quiet and calm, away from distractions (no internet service!) that had kept me from facing the difficulties I’ve been working through.”

WHY THIS WORKS

You’re still announcing new work, but now you’re giving insights and personal reflections that will resonate with your reader. If your reader is interested in your work, they will now have a deeper understanding, which is something collectors are always yearning for.

In other words, you’re giving people the story behind the art.

And, not only are you giving people a glimpse into your practice, but you are being real and showing them that you–like them–face similar challenges. It’s all about helping.

Ultimately, your clients will feel a connection to you because you are being authentic. They will further feel connected to your work because they too have had to deal with difficulties.

Of course, it doesn’t have to be difficult times. It can be joyful times, too, like the birth of a child or the addition of a new furry friend.

The thing is, you’re an artist but you’re a human being, too, who is dealing with the same basic needs as every other non-artist. Find connection through the human stuff; use your art as the catalyst for the conversation.

Compelling Reason #2: Blogs

Blogs on your website are akin to having a personal magazine. A blog allows you to do what Social Media won’t: spread out and tell your story.

Newsletters are the vehicle to drive people back to your website. Blogs are the destination. Newsletter are timely; blogs are usually evergreen.

Newsletters go out in e-blasts that land in your clients’ inboxes then go away. Blogs stay on your website for years where they remain searchable. Searchable content on your website means it’s constantly working to reach collectors long after you hit publish. Newsletter, on the other hand, are a one-and-done deal.

5 Reasons Why You Should Blog

- Drive people back to your website. The ENTIRE reason to send a newsletter is to bring people back to your website. If you’re not sending them to your website, you are missing a golden opportunity.

- Build SEO. SEO (search engine optimization) is the great, organic stuff you do on your website to get discovered. Having a blog that talks about topics that people looking for work like yours are searching for is better than buying ads or boosting social media posts that are only randomly found.

- Content lives on your site, working long after you hit publish. This content, when done right, keeps working because people from around the world who are looking for answers can find you through your blog content.

- Establishes you as an authority. This space is all yours, and you are an authority on your work, your genre, your materials, your studio, etc. So get out there and talk about it.

- It’s shareable. People who read your blog can repost it on their social media or email to their friends. Suddenly you have a sales force out there sharing your insights and driving more people to your website.

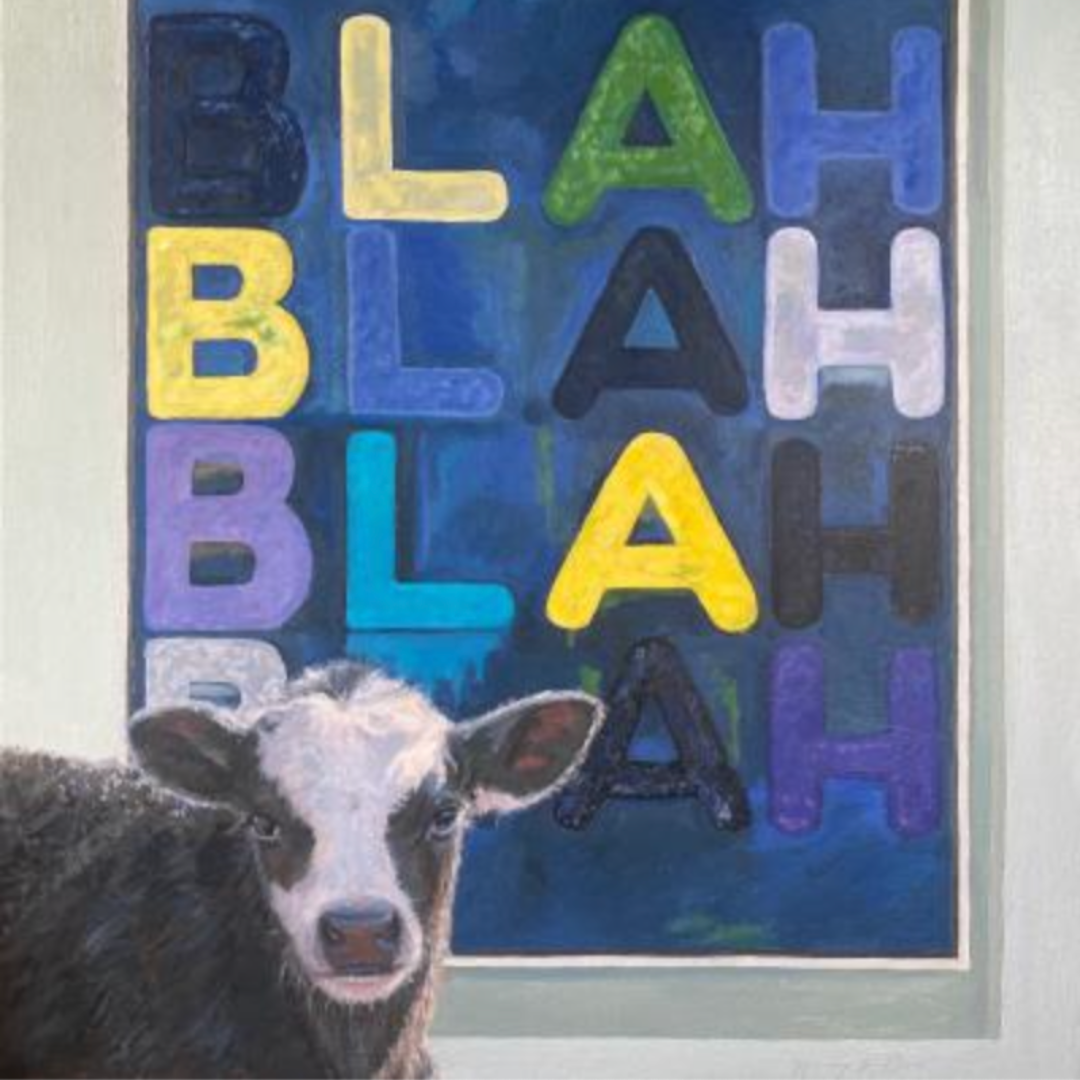

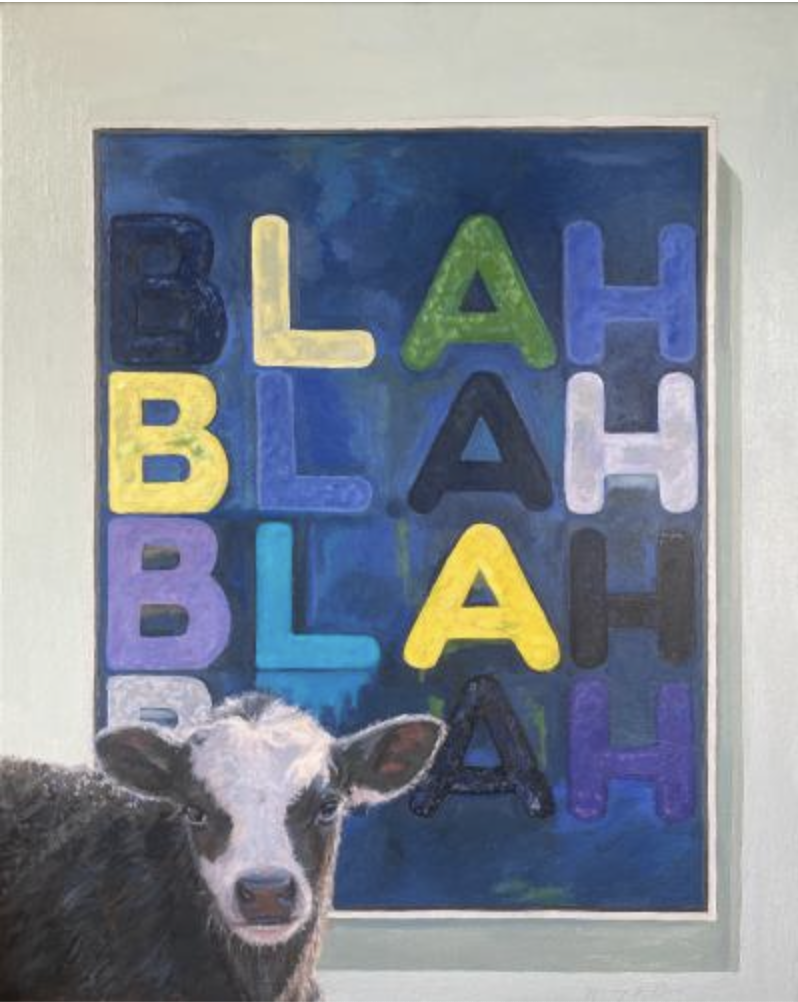

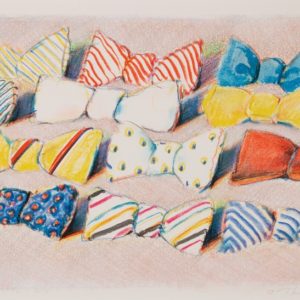

Compelling Reason #3: Use Your Images

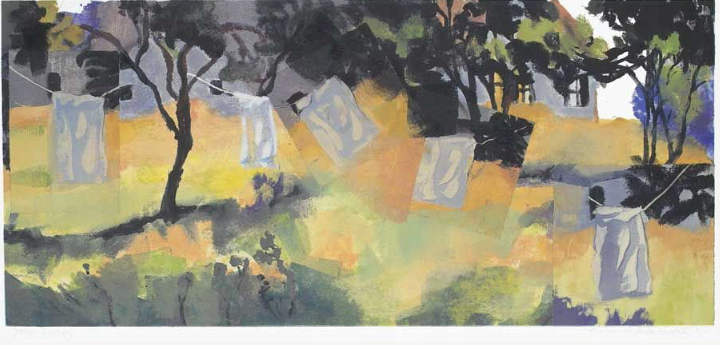

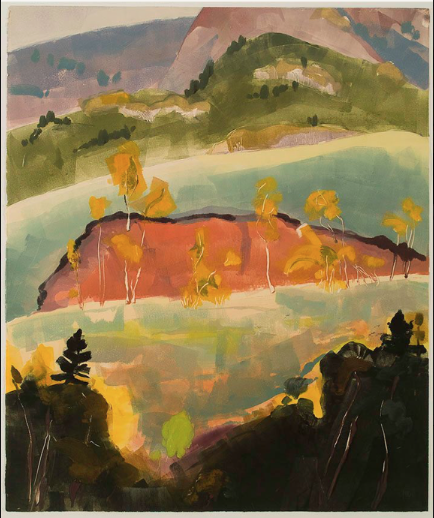

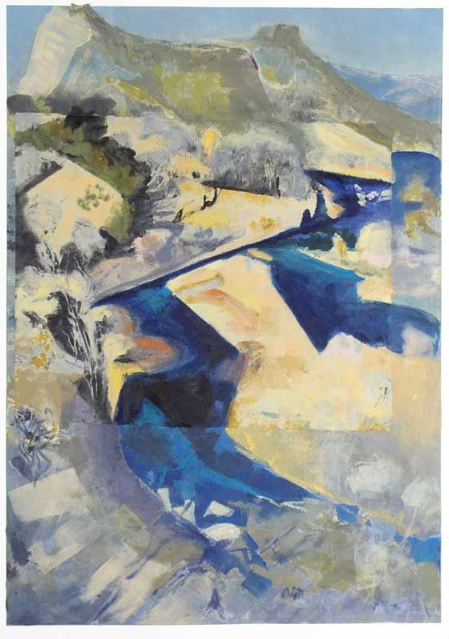

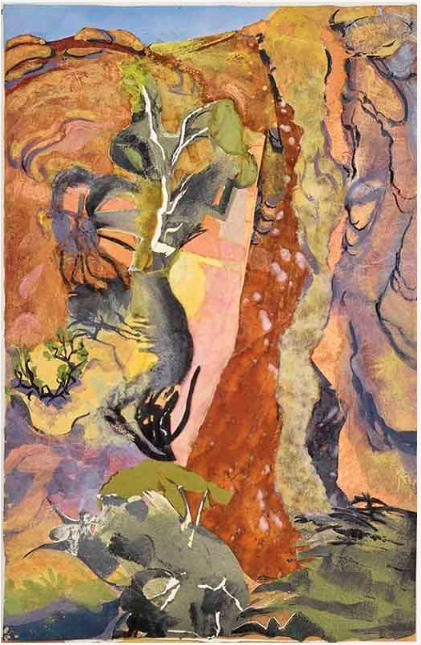

You’re an artist. You have images of your work. You don’t have to be a stellar writer to make really great blogs. In fact, you can work magic marketing your art online and create a loyal following by using your images. Here’s how:

- Gather together images that have a cohesive theme.

- Simmer that theme down to one clear topic that answers a question your audience has.

- Make the topic something that people would look up when searching for you. Example: you’re a watercolorist. Collectors of watercolors frequently search “how to display watercolors.” Focus on this searchable topic.

- Optimize images for the web (your website will have recommended dimensions and files sizes–check out these standards and convert images appropriately).

- Write short paragraphs or longish captions that explain the images and how they help answer the question of how to display watercolors.”

- Link out to any and all terms that are appropriate. Using our Watercolor example, you may refer to certain types of glass. Link out to manufacturers of that glass.

- Link internally. Every image on your blog should be linked to the image where it lives on your art page.

- Use your key phrase throughout your blog, i.e. repeat your key phrase/established topic.

- End your blog with a call to action (CTA). This might be asking them to subscribe to know when your next blog is published or maybe to email with other questions about displaying watercolors (you are the authority, after all).

- Before you hit publish, ask a friend to read for content and typos. If you’re like me, you can find other writer’s typos but not your own.

- PUBLISH!

- Send a newsletter.

- Post your blog on all your social media.

Want Some Help?

Join me for a Blogging with Pictures workshop. I run them monthly. (Yep, that’s a Call To Action, my friend! You’ll learn about those in my workshop, too.)