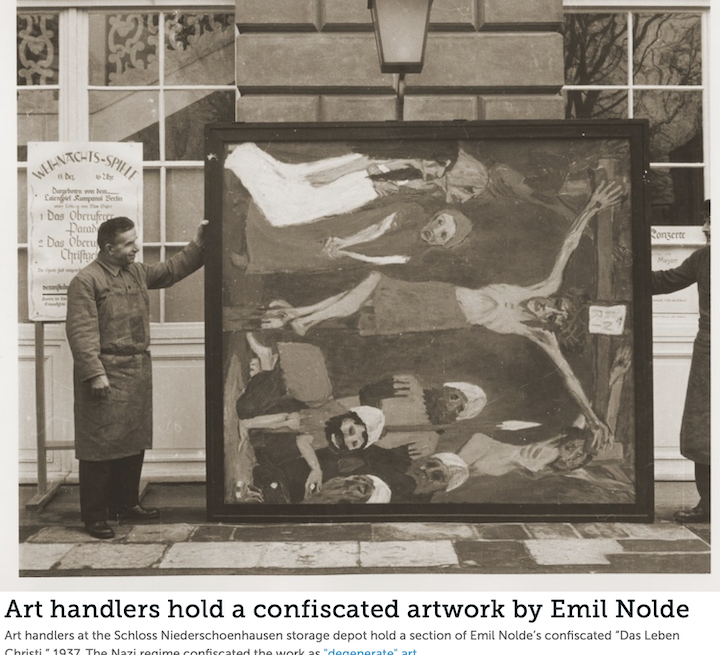

You’d think that as much as artists hate to be pigeonholed, the art world wouldn’t act like a bunch of kids on a playground hurling names at one another. OK, sure, names and labels make for an easy shorthand, but they can also be used to minimize and even disregard entire genres of art.

Take western art, for example. Wow, does that label come with some baggage. Over the nearly 30 years I curated the Coors Show, so many people told me they hate western art. Hate. I get it; the genre is packed with cliches. But what about all the artists who live in this region? What do they call themselves? And how about artists who paint western subject matter in a novel way? Should we pass them over, too?

For my next show, “Icons for a New West,” now on display at Gallery 1261, I talked to artists who are doing what I consider “contemporary” western art. In other words, they are not shying away from iconic subject matter but instead are looking for important things to say about the West. Here’s a deep look at what these women and men are doing.

Reframing Icons

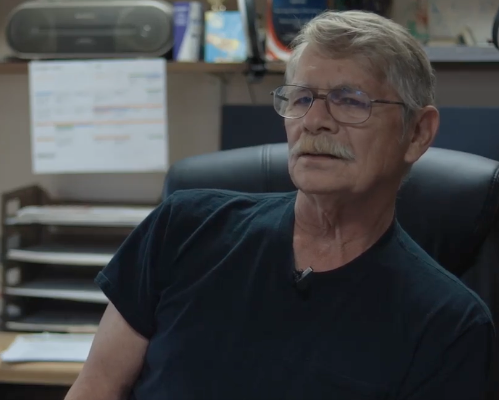

Artist William Matthews has been boldly embracing the moniker “western” artist for decades. A true autodidact, Willy possesses a larger-than-life personality and seemingly endless supply of curiosity and energy.

Where many artists visit a rodeo and paint from photos, Willy paints his long time friends–ranchers living off the grid, cowboys with more years in the saddle than they can count, as well as the land he has traveled since he was a boy.

The paintings I curated into this show took my breath away, this one presented here in particular. How iconic is the train to the West? And how many times have we seen it painted? But when has an artist put you above the train and left you with more questions than answers? This is why Willy is a master.

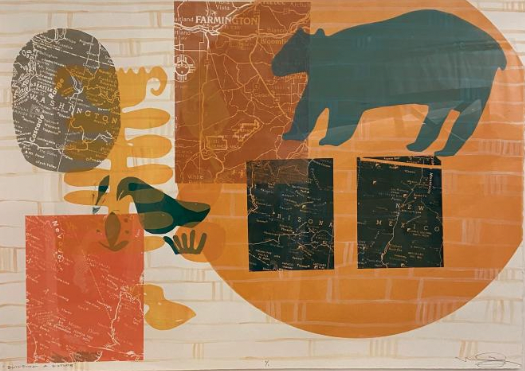

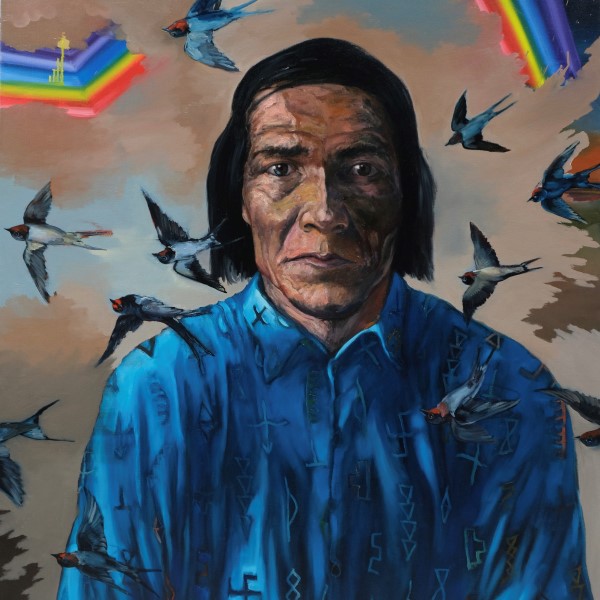

I love seeing Melanie Yazzie‘s work in the context of any western art show. A Navajo and master print maker, Melanie teaches at CU Boulder and taught printmaking and exhibited her work around the world. I always tell collectors to look at the work Indigenous artists are creating; it’s unlike anything else being done today. The pieces I have in the show by Melanie (please email me to see more), are joyfully filled with layers of meaning.

I will never forget a conversation I had with Melanie about her earlier work when she was just out of college. She said her work was angry–because she was angry at the injustice of this country and how her people continue to be treated. But then she realized the people she wanted to listen to her and understand were not paying attention because they had written her off as another “angry Indian.” So, she changed her mindset and with it her work changed, too. Now she creates art that draws people in and encourages them to ask questions, to see this place through a new lens.

A Sign of the Times

Don Stinson once called the Rocky Mountains a “celebrity landscape.” I like that term and think it’s quite fitting. This land has played a leading role in western expansion, the preservation of public lands, and national parks. But maybe this land is a little too pretty. Maybe it’s too easy to leave out the very real issues facing the West. Not that everything needs to have a message, but artists have been throughout time our best observers and voices calling attention to problems facing mankind.

I really like Gerald Peters Gallery curator Evan Feldman’s statement about Don’s work: “The tension in the American landscape is not always represented in landscape paintings. Instead, often we see a pastoral or romantic respite from the urban, industrial realities of our contemporary lives… [A]rtists challenge us to see beyond the romantic and embrace the everyday presence of the art in our midst. Their work inspires us by drawing attention to both the cultural complexity and sublime threat of human presence in the western landscapes of our time.”

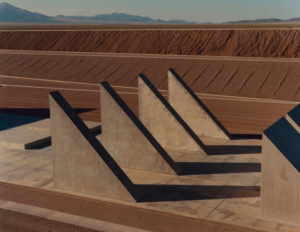

Similarly, fifth generation Coloradan, Stephanie Hartshorn‘s work is all about that exploration of the land. In particular, her depictions of iconic western signs draw attention to these obtrusions on the land that have marred–and decorated–our landscape since the first automobile hit the road.

“My family came from Germany and started a cattle ranch east of Colorado Springs,” she says. And she added, “Themes in shows are typically very male-centric,” she says. “There are fewer female artists in the field and fewer still who paint architecturally. There are times that people are surprised to discover that I am a woman…and I’m OK with that.”

Art Deco, Meet Western Art

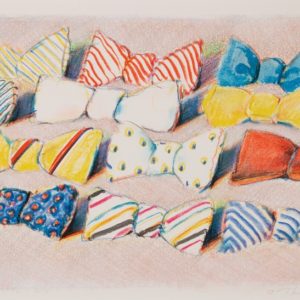

I adore Tim Cherry‘s work so when I finally met him, it was no surprise that he is as kind and joyful as his work. His work is a rather interesting combination of ideas, something great artists meld flawlessly. Tim honed his animal anatomy skills as a young man working in taxidermy. His penchant for Art Deco developed around the same time and emerged out of his love of art and architecture that incorporates smooth, stylized lines. The thread that pulls it all together: his most delightful sense of humor. How wonderful to see the familiar through Tim’s eyes.

On the Edge

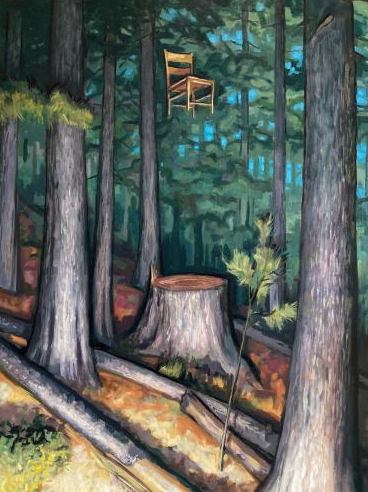

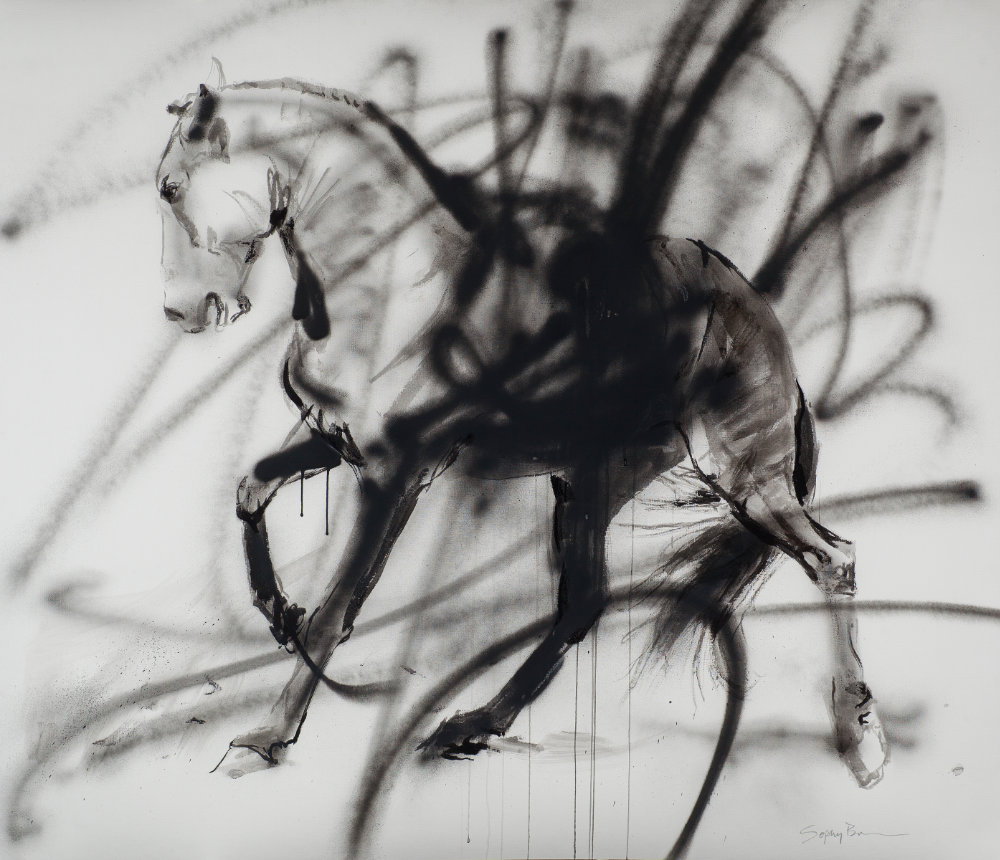

When a painting holds mystery, it keeps calling you back to try to figure it out. The wonderful thing is that the painting changes as you change. It’s kind of like picking up a book you read in high school because you had to. You read with a mind that hadn’t experiences nearly as much of life as you have now. So, rereading that book, you will see and feel it differently and memories will come back–or you will realize that you don’t remember parts at all. So, much is painting like life–it’s full of memory and meaning that we attach to it. Mikael Olson is one of those dreamy painters whose work is always on the edge of complete abstraction, kind of like he’s painting memories more than scenes.

Larger Than Life

It’s common for sculptors to create monumental work for parks and public collections. What I absolutely adore about Tony Hochstetler‘s work is how he takes the tiniest of sentient beings and sculpts them into monumental statements–well, monumental for a seed pod or a snail, that is. In so doing, he extracts the lovely natural patterns and forms and works them into art that seems to dance into life, like the servants from Beauty and the Beast who were magically turned into household objects. Really, how can you hate a set of dancing snails illuminating your home with warm candle light?

Can We Talk?

There’s something about a paisley silk covered gun that makes people stop and engage with one another in a surprisingly sensible way. And so, while pundits shout about gun rights and violence but never accomplish anything, Corey Pickett has taken a different approach. By sculpting guns as upholstered art objects, Pickett has been able to neutralize the heated conversation and get people to slow down and ask questions.

Corey’s Ray Gun series is a particular favorite of mine. It’s his interpretation of Afrofuturism, the African American Science Fiction genre of literature where black protagonists explore the relationship between humans and technology. Once again, art leads the way. (right: Ray Gun 56, wood, foam, fabric, 16 x 15 x 13.5 in)

Out of Context

Amazing, isn’t it, how art can make us reconsider what we already know–or think we know. I love Michael Vacchiano‘s playful reimagining of horses–this one having a good roll after a long day–but in a surreal bed of flowers. And Reen Axtell uses her wit and design skills to combine old photos with stamps, text, architectural drawings, and paint to create knew stories about the past.

Playing with Pattern

Speaking of patterns, isn’t nature genius at patterning? No wonder the western landscape and wildlife are such terrific inspiration for artists. Jeff Puckett‘s photo “Arches Aerial,” Kate Breakey‘s “Leopard Moth” photo/mixed media painting, Johanna Mueller‘s print “Coyote Wreath,” and Dianne Massey Dunbar‘s sunflowers “Reaching Higher” all revel in nature’s sublime patterning.

Metaphorically Speaking

David Carmack Lewis is one of my favorite western painters who plays with themes and dramatically uses light and subtle color to lead you through paintings that often feel like fairytales, or as if you’ve just stepped into a play and now it’s up to you to figure out where you are in this made up world.

Here’s an interesting thing that happened to David. A French poet stumbled upon his work and wrote an ekphrastic poem in response. He sent the poem to David, in French, which David translated. Twelve more poems came after that, each a poetic response to a painting. The poet, Michel Lagrange, was born in 1941 and had been publishing poetry since the 70s was a former classics professor and a Knight of the National Order of Merit. David published a book of these thirteen poems and the paintings that inspired them. It’s a lovely book–check it out here: Seconde Main.

Welcome to the Sublime

It always amazes me how Linda Lillegraven captures so much light and depth in the most quiet of scenes. I have watched collectors approach her work, pause and then look around for someone to talk to about what they are feeling. A longtime resident of Laramie, Wyoming, Linda paints not only the land but the atmosphere, a light breeze, the scent of an approaching storm. She is undoubtedly one of the greatest artists to call Wyoming home.

I thought I knew Susie Hyer‘s work–traditional representational work. Then she asked me to curate a show of her work for her alma mater, Moravian University, in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. On my first trip to her studio in Evergreen, Colorado, I was blown away. The work she had been doing was abstractions of the land and they were gorgeous and moody and etherial. So, why, I asked, wasn’t she showing these? She said her galleries didn’t want them. So, here was this incredible body of work that was so clearly her authentic expression. I knew then that I wanted to show her work.

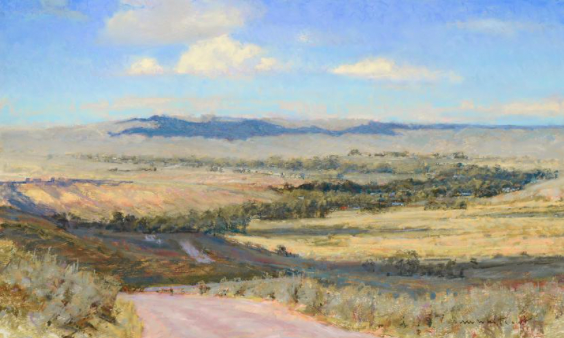

Missouri born and raised, Billyo O’Donnell paints in thick impasto strokes of pure, vibrant color. Coming west, he worked outside, on location and often camped out. The paintings we have in this show are some of his plein air work.

Of his work and painting on location, he says, “I am focused on the visual experience working from life and in the studio to develop the surface quality of a painting that is rich in texture. I often play with how the two relate, how they struggle for the viewers attention, how the surface language takes you from the image into the paint through a language all its own in structure and abstraction.”

Daniel Sprick is a master of the sublime. His painting “Iron Mountain,” is the view from the deck of his old studio in Glenwood Springs, Colorado. He was looking east at the mountain and his neighbors’ houses. “The afternoon light,” Dan says, “was the sun settling down in the west, behind me but the light was in front of me, so it’s rich and vibrant and dramatic.” The flowers are a familiar subject matter. Here, on the ledge in the shadow, Dan sets a small vase with roses, a favorite element. “I like to combine still life and landscape,” he says of the water and glass vase, which does something more; it turns the whole image upside down, giving the whole painting an added sense of mystery.

You Just Gotta Laugh

Tall tales and anthropomorphizing animals is so very much fun. Clay sculptor Dwight Davidson has been finding humor in the quotidian for years. Interestingly, I met Dwight when he and I were asked to be judges fro the Breckinridge Snow Sculpture Championship. It’s been a lot of fun hearing him discuss sculpture because he sees art in three dimensions, which may not sound earth-shattering, but it is cool to have someone like Dwight articulate what his mind is processing.

Linda Prokop is an absolute delight. She’s been in the biz, living and working in Loveland, CO for decades. But as Stephanie Hartshorn eluded, being a woman in the traditionally man’s world of western art is not easy. But Linda keeps playing with myth’s of the west and has fun presenting them through her feminine lens.

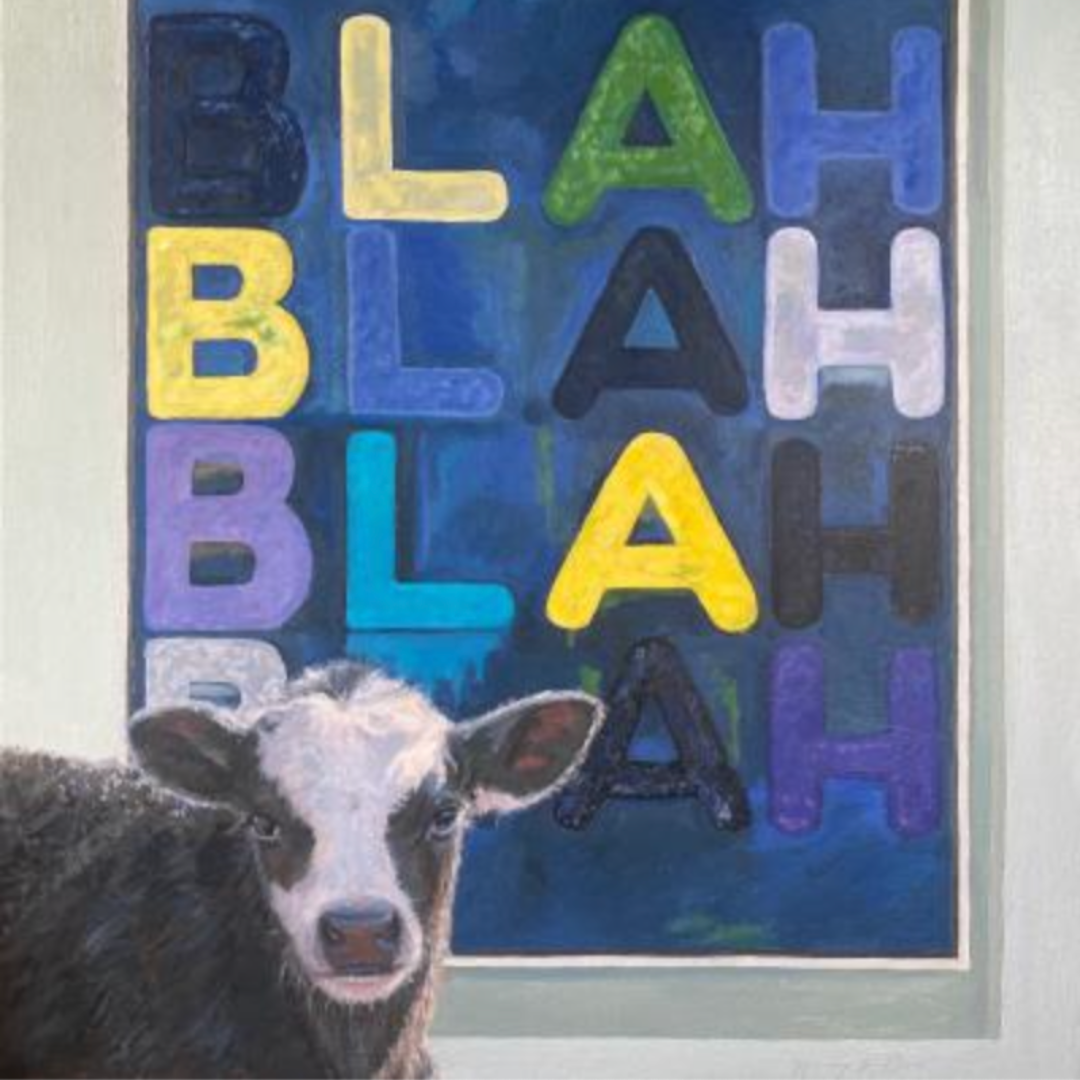

And Elsa Sroka–an artist who has developed her own iconic style, not because she was trying to but because it just came out of her mind that way. You can see her work on the side of buildings and, of course, in my show. Cows are a favorite subject matter for reasons beyond their interesting form and familiarity; they make merry when dropped into human settings and beckon viewers in a quirky, non-confrontational manner. Basically, Elsa’s paintings are hard not to engage with.

Go Ahead, Take a Chance

Let’s face it, an artist’s life can be challenging, to say the least. But they can’t let fear lead the way. When that happens, they become what Wayne Thiebaud called “art world employees.” Sure artists have commitments and need to sell work, but they also need collectors who believe in them and are eager to see where the artist goes next.

Two artists in this show have recently embarked on a new exploration. Terry Gardner, above, is considering how light plays through the branches of trees and, in turn, how that abstract idea can be translated onto paper.

Dan Young is also searching for a more simplified way to express his sense of the western landscape. He’s also coming up against, well, himself and his own style and habits as a painter.

So Ugly They're...Gorgeous

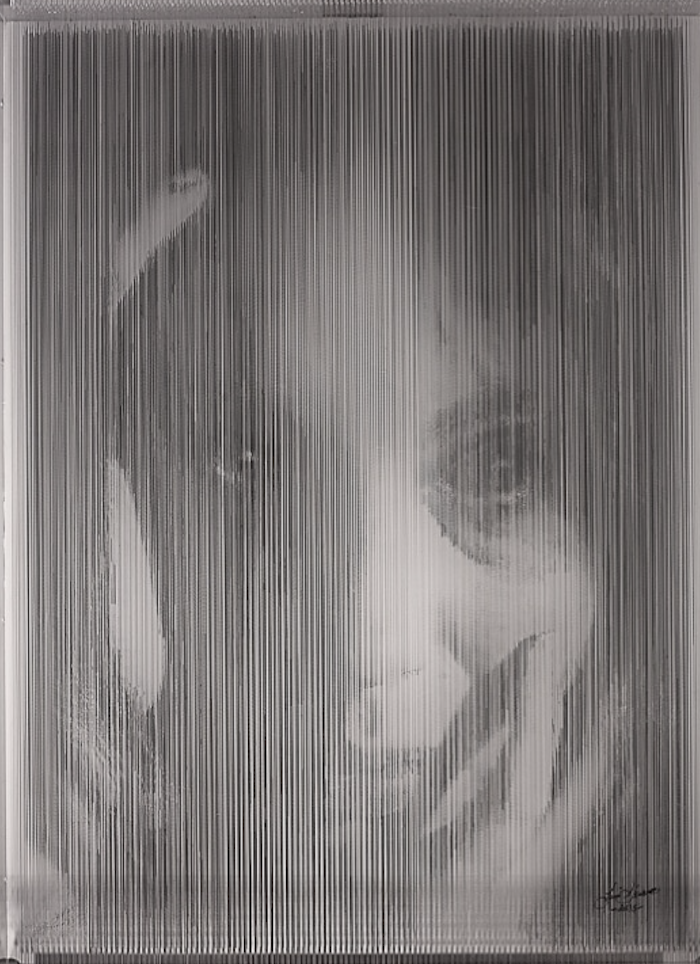

Lee Andre started drawing with charcoal and experimenting with plaster-like surfaces as a way to see what happens when powdery charcoal blends with a soft, mutable substrate.

As for why she paints wildlife, she says that animals offer more intrigue for two reasons: it was an endless subject matter and one that held opportunities for deeper emotional connections.

Lee isn’t, however, interested in in depicting the majestic beasts. She prefers the, well, ugly creatures.

“Lee brings a real emotional aspect to these animals,” a friend of hers told me, “in a way that makes you appreciate this beautiful earth and all its creatures.”

Is Western a Place or an Idea?

Like a scrabble game with a finite set of tiles from which players can create an unlimited series of words, our notion of what is western is only limited by our imagination. And isn’t that the trouble with labels? Suddenly, parameters have been set.

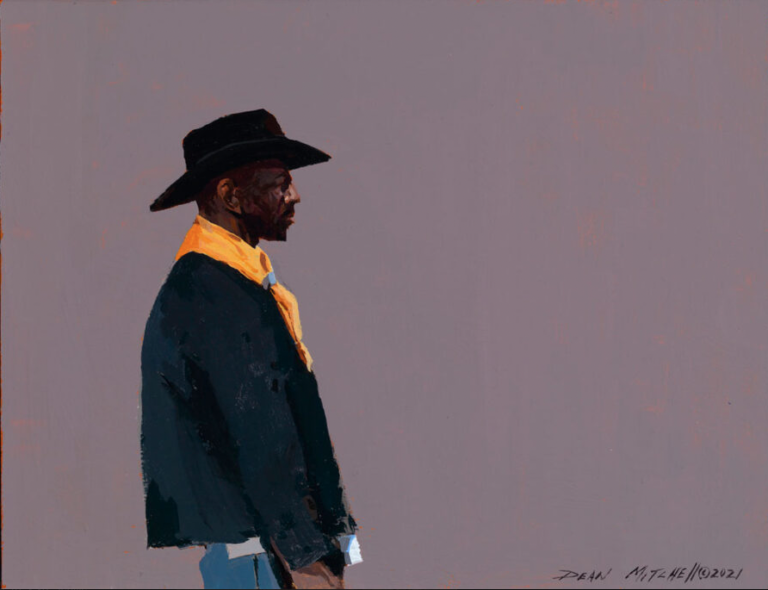

I like Charles (Chuck) Parson‘s thinking about the West: “I believe our culture has lost sight of the individual in favor of sameness. We have become superficial and driven by fitting in, looking and acting the same. But beneath it all is a Western sensibility with its roots in the ideal of the individual roaming freely through the landscape.” Chuck incorporates traditional mediums and styles of working with contemporary. Now in his 80s, Chuck is still a restless artist searching for new ways to express his devotion to the western aesthetic.

Ulrich Gleiter, a German artist who is also constantly in motion traveling across Europe and coming to America every chance he gets, reminds me that there are no real boarders; the land and the elements are eternal–we are the temporary ones.

Jen Starling‘s painting, Metamorphosis, hints at this very thought.

And, I love seeing Quang Ho‘s work in this mix. I wonder, as an immigrant who escaped from a war torn home, will he ever feel at home? But then again, maybe that’s the feeling of the West that so many artist embrace in their own way: home is not a physical space so much as it’s an idea.