This month, March 2023, marks the end of an era. After 27 years building the Coors Western Art Exhibit & Sale, an exhibition under the auspices of the National Western Stock Show, several men on the Board of Directors at the Stock Show, none of whom collect art anymore (or ever did), have decided to eliminate my position as curator.

Yes, you read that right: the Coors Show will no longer be an independently curated event. A committee will decide.

The art, I have been told, will reflect them (white men) and their traditional values, whatever those are.

Is the hair on the back of your neck standing up? Art + committee + traditional values…. Yeah, it hurts my heart, too.

Uninspired

This is an old story. Art exhibition has great success; egotists take over after deciding they can do it better despite having no understanding of the art market; art show dies; no one cares.

It’s not just art shows either. Think of all those funky neighborhoods where artists lived and worked until someone thought it’d be really cool to buy up the shabby-chic (read: cheap) real estate and suddenly the neighborhood becomes a cookie-cutter version of every other formerly artsy outpost. Rents go through the roof and the artists can no longer afford to live and work there. Creativity grinds to a halt without artists and soon the cool neighborhood becomes another cliche.

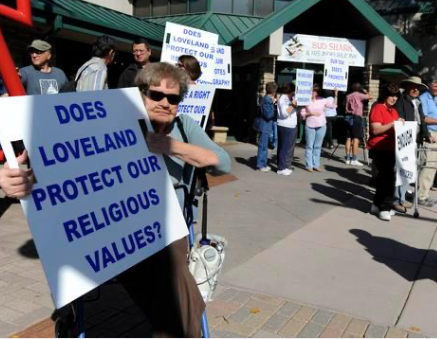

The Big Backlash

When I told the Coors Show artists what was happening and that I wouldn’t be back, many reached out in texts and emails expressing their anger and incredulity.

One conversation in particular set me back on my heels. Melanie Yazzie, master print maker and a university professor said that this kind of thing was happening all over academia.

What we’re seeing across the country, she told me, is a backlash against the #MeToo movement. Out of fear, certain people are doing everything they can to maintain control. They’re deceitful, conniving, and ruthless.

As she talked, I flashed back on the years working in the National Western culture of good old boys and saw vividly the scene that decided my fate.

Minding My Manners

Last year, I and two other women filed a complaint against the CFO of the National Western for bullying, harassment and retaliation. The president of the National Western, which is the company I worked for as curator of the Coors Show, hired an outside firm to interview everyone and, well, cover their asses.

Well behaved women rarely make history.

Our intention in filing a complaint with the National Western was not to be litigious but to make the bully stop.

What happened, however, was jaw-dropping. The man with the outside firm who conducted the study came back with his findings: the women were not credible; the man was.

When my contract was up, I was offered a “constructive discharge,” i.e., a contract written to force me out. In the contract were two stipulations. One, that the National Western would select a committee to curate the show with me (that committee would then take over in a couple years, presumably, after I trained them), and two, because of my “problems” with the CFO, I was not allowed in the offices where he was–which are essential to doing my job.

The bully is protected. The bullied is shamed and fired.

Yes, this is still 2023. I just checked.

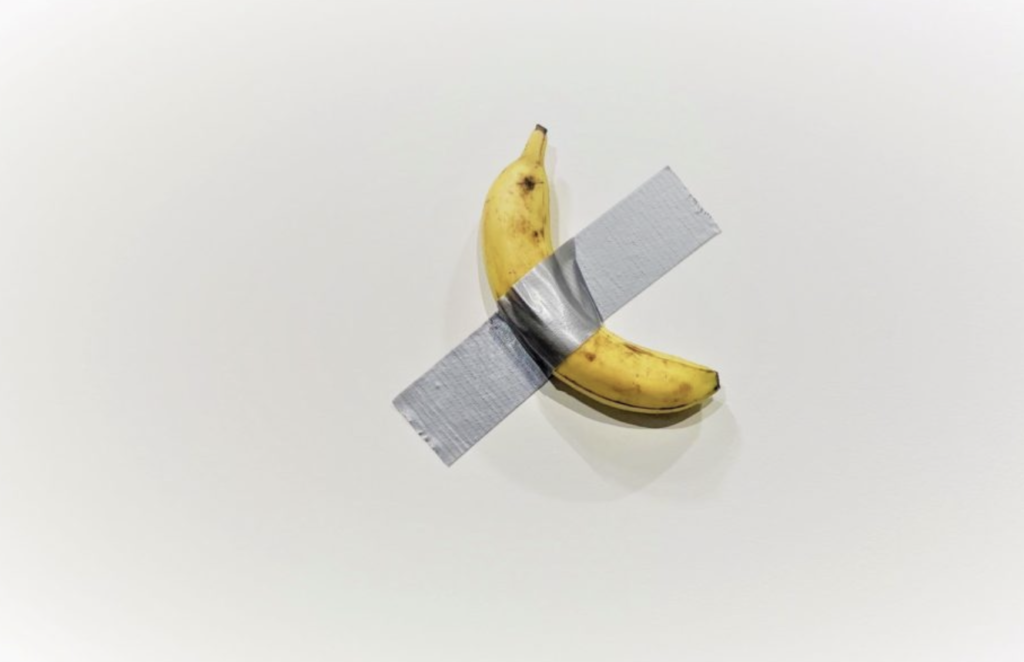

When Committees Tell Artists What to Make

There are numerous reasons why art by committee guarantees a weak, milquetoast exhibit and mediocre art.

First is the committee itself. Who joins a curatorial committee? Often it’s collectors with a limited palette. They have, thus, a dog in the fight; their goal is to substantiate their own collection and stoke their egos. They often know enough about art to be dangerous. They purchase what they like, not what is artistically important.

Next is the problem of casting off anything that offends anyone on the committee. When all the offensive work is removed, what’s left is safe, mediocre.

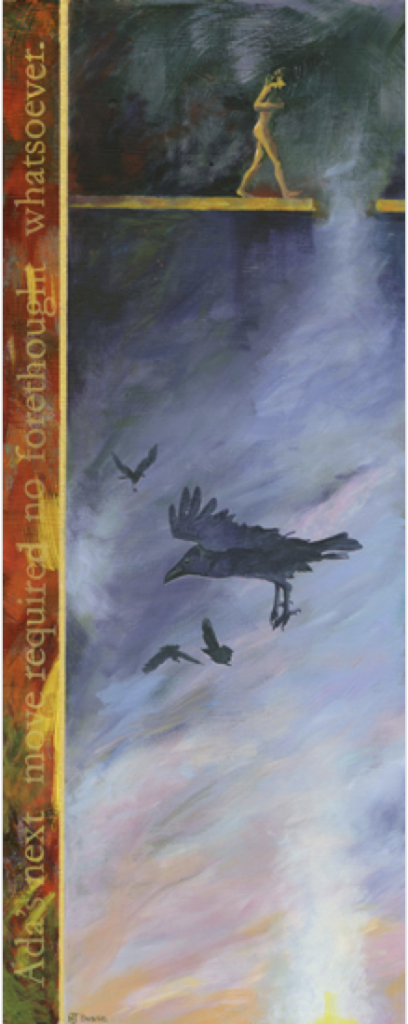

And then there’s the issue of censoring and silencing voices. Artists who need the show and rely on those sales will rein in any thoughts of pushing themes or style or subject matter. Safe gets you in; experimentation and expansion of ideas gets you kicked out.

When Politics Trump Art

Throughout history, politicians and religious figures have imposed their will upon artists, writers, and philosophers. In 1633, Galileo was found guilty of heresy for saying the earth rotated around the sun, not the other way around. He lived the rest of his life under house arrest. By the way, it took the Catholic Church more than 300 years to admit they were wrong and clear Galileo of heresy.

Oscar Wilde was convicted of gross indecency with men and jailed from 1895 to 1897.

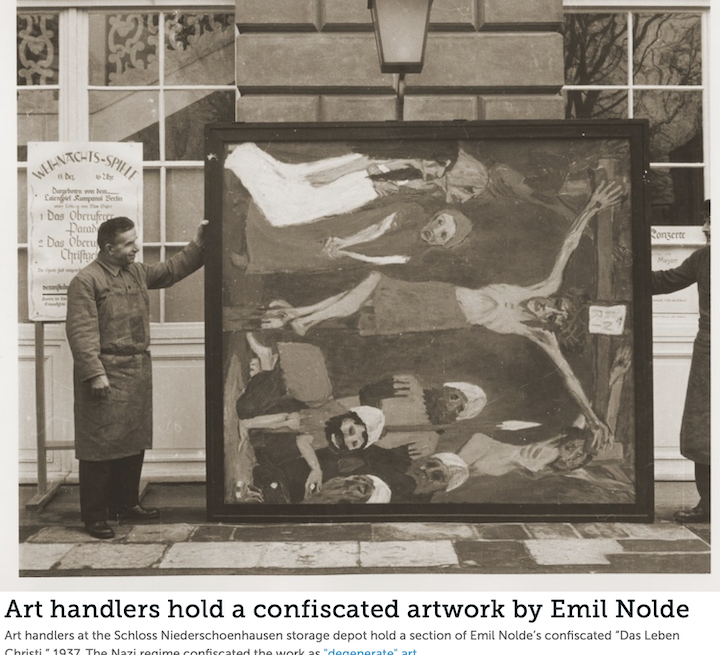

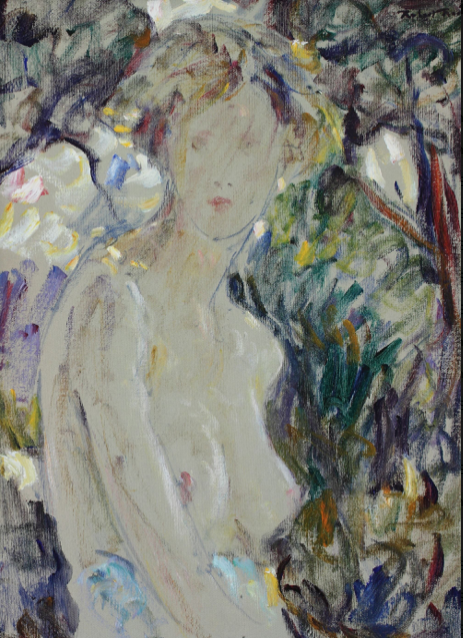

And then there were the artists in Europe in the 30s and 40s who had the audacity to make work that pushed forward the ideas of what art is and its purpose. When Hitler came to power, part of his hatred was turned on modern art and the “degenerate” artists who made such things. The only art permissible was that of bucolic countrysides or heroic images of beautiful Germanic people.

Stalin, too, mandated that art could only depict the communist party and people in a positive light. Art created during his reign was used as propaganda to convince citizens to fight for the motherland and that the conditions under which they lived were really not so bad.

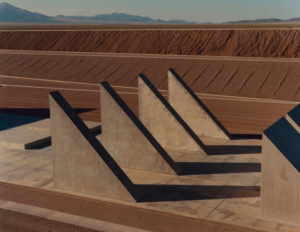

From where I’m standing, I see modernist structures, and the only hint of a classical building I can see is the top of the U.S. dome. That is not what our founders had in mind.

In 2020, then President Trump signed an executive order called, “Make Federal Buildings Beautiful Again.” This order, which has since been rescinded, put forth that all new federal buildings should be beautiful because the “modern” federal buildings, according to Trump, are “just plain ugly.”

Ah, hubris….

Forgetting we belong to each other

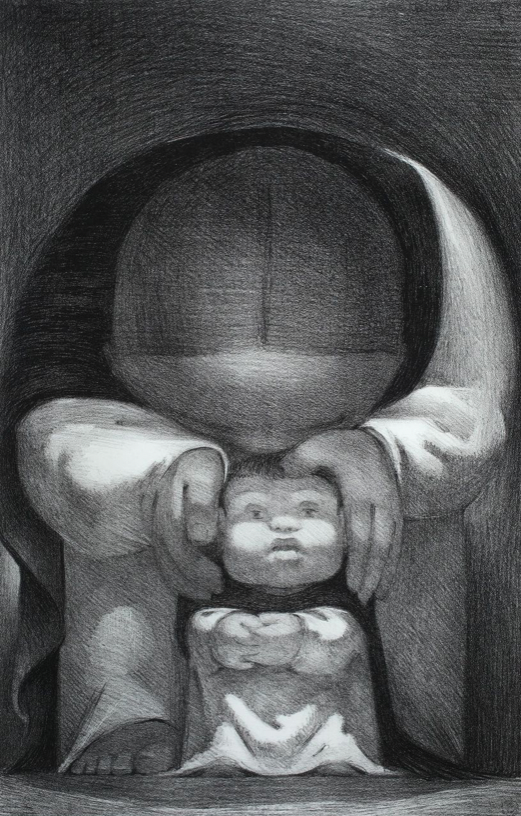

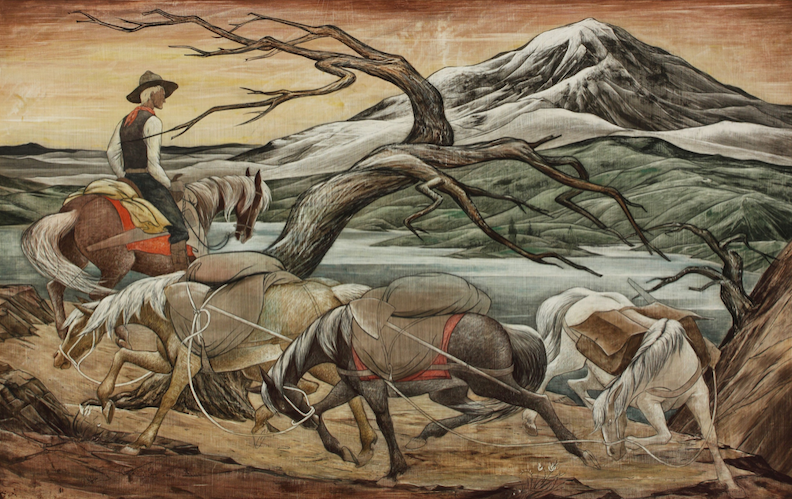

Western art is the ugly stepchild of the art world, with good reason. Traditional Western artists who strictly adhere to the genre are often white men who paint pictures of cowboys and Indians. These old tropes are not only derivative but reductive; they perpetuate prejudice and lies. As Dakota Hoska, the curator of Native American Art at the Denver Art Museum curator put it: “Why don’t they tell their own story?”

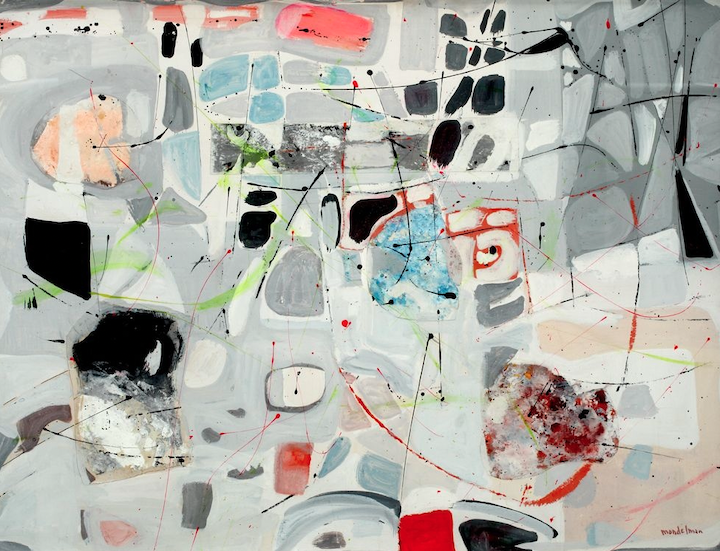

My goal as a curator of “Western” art was to exhibit art pertaining to the Western U.S. that was relevant and vital and alive. Because we are a strong community of artists, the vast majority of whom want to create work now, not work that looks backwards.

Curating the Coors Show for nearly three decades was more than a job to me. It was a community of people who brought fresh ideas to the table, each and every year. We made something that challenged the common perspective but did it in a way that invited conversation. The show was, ultimately, a place where artists could be seen and have a voice.

It’s bigger than a job. It’s bigger than sales. It’s about being part of this life. It’s being human and understanding the true meaning of what Mother Theresa diagnosed as the ills of this world when she said, “We have forgotten we belong to each other.”

Blessings in Disguise

Recently, over lunch, I told a dear friend what happened. After listening patiently, he sat back, took a breath and said, “Congratulations!”

He meant it. And though I wasn’t quite ready to look back and laugh, his comment did help me put things into perspective.

After nearly three decades working to build something, it was time to move on. I would not have left had I not been pushed.

And, so, what else is there to do but feel grateful, turn the page, and start anew.