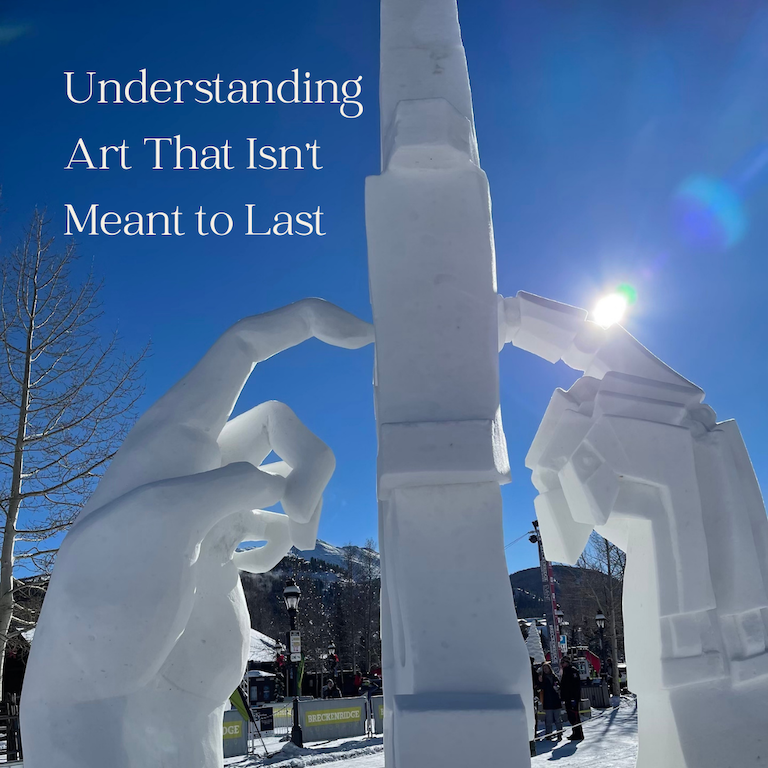

As one of the judges for the 2022 Breckenridge International Snow Sculpture Competition, I had the opportunity to ask a bunch of artists one of my favorite questions: Why?

In this case, WHY create art out of snow, under these conditions, knowing it’s gonna melt–that it’s probably melting as you work?! Talk about a bunch of incurable optimists….

A Container of Essence

In the art world, we’re all about collecting and preserving things that are important testaments to our life and times. And other cool shit. This ideal gets challenged hard when presented with objects that weren’t preserved properly or couldn’t be preserved–frescos, old photos, film, paintings on unstable substrates, stuff like that–or with art that was never meant to be collected in the usual way.

Sand mandalas created by Buddhist monks come to mind. In this case, the “art” is not the end result but the process that brings forth “an internal awakening to the desire to let go of attachments.” The act of wiping away the mandala, therefore, is part of the art because it completes the “letting go” process.

But, geez, there’s nothing left and hardly anyone got to see it! (And by “anyone,” I mean me.)

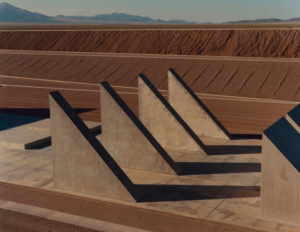

Earthworks and land art, in a way, are the creation of mandalas on a monumental scale. The “canvas” is nature which, for a time, allows the artist to create a transformative experience and bring attention to important issues, such as the environment. These works of art are transitory but, for the time they are around, we get to see the familiar through a different lens. Land art isn’t, in my mind, so much about letting go, however, as it is about realizing what we unwittingly let go of when we stopped caring, or weren’t paying attention.

Here’s a wonderful article in Artland Magazine, about pioneering earthwork artists.

So, you may be wondering, what kind of zen fools make art like that? Excellent question. Honestly, I don’t know. I do have a guess as to Why, though.

A Place Where Art, Nature & Booze Collide

I had the great good fortune of being asked to help judge the 2022 Breckenridge International Snow Sculpture Championships along with Alex Kendall and Tina Rossi of Breckenridge Gallery and sculptor Dwight Davidson.

I must admit, this task made me nervous. I do a fair amount of judging and jurying of art exhibits, but snow sculpture–monumental snow sculpture–was a first.

Turns out judging a new medium was the least of my concerns. I hadn’t fully accounted for the conditions. Obviously, it’s gotta be cold to sculpt snow, but this means judging happens, basically, in a meat locker. (Thus the booze, I’m thinking.)

No Pansy-ass Power Tools Allowed

The day I arrived, sculptor teams of four had already put in three grueling days carving with hand tools (power tools are strictly prohibited), on 12′ x 10′ x 10′ packed blocks of snow. That night, while I was tucked into a warm bed, many teams were working until dawn to complete their sculpture by 9:00AM when judging was scheduled to begin.

Yup, snow sculptors are some hearty folk. I’d go so far as to say that if snow sculpting were an Olympic sport, these artists would be the biathletes–you know, the crazy cross country skiers who stop every so often to shoot at, I don’t know, slower skiers? Snowboarders? (Seriously, who does that sport?)

Now that I think of it, snow sculptors would totally do that sport. All this to say, snow sculptors are tough as nails. And zen as hell.

A Quixotic Journey

Founders of the Breckenridge Snow Sculpting Championships, Rob Neyland and Ron Shelton, have competed with their own team all over the world for the last 40 years and have a bunch gold, silver, and bronze awards to prove their chops.

Their understanding of the art form and how these competitions unravel was vital knowledge for us judges.

In a nutshell: teams spitball concepts, someone is then tasked with the duty of creating a clay maquette (a miniature sculpture of the idea), the team applies to competitions, and, if juried in, they put themselves through four intensely exhausting days of carving under pressure, in extreme conditions. Fun, huh?

Here’s a pic of Rob Neyland and team’s maquette for “String Theory.”

Teams are not just competing against each other’s concept and sculpting feats, but they are also working against the elements. A bright sunny day could weaken a sculpture to the point of collapse and utter ruin. Nights that don’t adequately freeze also spell danger because the snow doesn’t have a chance to freeze and begin its transformation into its more stable crystal-like form (think of snow as very, very slow running water).

Here’s the completed sculpture. Note to man standing to the left to get a sense of scale.

And then there’s the rather dubious blocks of snow these sculptors get to carve. For example, the block provided by the Milwaukee Zoo, Rob told me, was replete with camel dung and the block in Moscow’s Gorky Park was laced with cigarette butts and beer cans.

But like the weather, funky blocks of snow are part of the challenge and the thing that ensures everyone starts on a level playing field.

FYI: Breck snow is some of the best in the world, naturally.

Here’s a pic of Team Breck’s gold-winning sculpture, “Frozen Moment,” at the Milwaukee Zoo competition. Note the lovely camel dung patina.

Cross Your Fingers

The morning of judging, Yours Truly–bright-eyed and bushy tailed (well, sober anyway)–arrived at 8:00AM, with my fellow judges to get busy sussing out the winners. Holy moly, what a transformation! The biggest change for most sculptures was that all supporting pillars of snow had been removed (check out before and after pics below).

I can only imagine how nerve-wracking that must have been, taking off the supports and hoping you got the weight ratios right. Apparently, this requires a slow and methodical approach where snow is gradually whittled down to a silver dollar-sized connection. Then, a few deep breaths and Hail Marys later, the final connection is severed about an hour before judging begins.

We judges were told that, if something collapsed into a pile of rubble before judging got under way, we could still consider that sculpture based on original concept and what we’d seen the night before. Thankfully, nothing went down in flames.

Transformative, Indeed

The thing that struck me about this whole event was that, once the sculptors put down their tools and stepped back, what remained of a 25-ton block of packed snow looked a lot like marble. There were even striations running though some works and large ice crystals that looked like chert.

Like stone, these sculptures also carried a sense of the memory of the hand that worked it, of the body that had to understand the need to go slowly, to feel and listen for the warning signs of a deep, internal fissure that might let go at the wrong moment.

There was also a sense of relief, a long exhale: the engineering worked. The temperature fluctuations were just right so that the snow became a different thing, a more solid form. The magic transformation that these sculptors listen for had happened: the dull thunking sound of hand tool against a freshly packed block of snow had taken on the singing quality of wine glasses meeting in a celebratory toast.

The Futility of Preservation

And so I asked the question of many sculptors over the days I was in Breckenridge: Why do something that can’t possibly last? Rob Neyland’s response is my favorite: “The notion of permanence is an illusion.”

Art created from snow sticks around for only a handful of days. You had to be there to make a memory, which is the only thing that remains of this art. All of which begs the question: What is art? Is it the final product or is it the effort, the performance, the motion of the body in rhythm with some flicker of an idea?

The men and women who compete in these events are artists, engineers, stone workers, restoration contractors, and other similar professions. They come for many reasons. Teams are tight-knit and have leaned over the years to move as one, in tune with each other and the sounds of the snow.

They also have a mindset grounded in humor that may stem from an understanding that all their planning and hard work could, if just one thing is off in the slightest, crumble into a heap moments before the competition ends. Which may be why they are also such soulful artists. I love what Team Germany wrote about their piece, “Float” (edited): “The subject lies in the geometric creation of order and maximum reduction to attain ‘esthetic essence’. It’s about balance and transformation. The goal of art is to develop objects for spiritual use, much as man designs objects for material use.”

How Do You Hold a Moonbeam in Your Hand?

Rob Neyland explained one of his team’s more esoteric works, titled “Water Song,” as capturing water for the briefest of moments and suspending it against the sky. He said, “We cast our fleeting form upon it but our vision is short-lived; it soon melts and resumes its journey to the sea.”

And so, as soon as the artists have set down their tools, the sculptures have already started their retreat back to ground. On the final day the exhibit is open to the public, there is a ceremonial bonfire lit within each work, hastening its journey back to the sea. The next morning, the site returns to a bustling parking lot.

I guess it’s a lot like life. No matter how hard we try to hold on, try to preserve beauty, beauty resists, beauty stays in motion. Memory, thankfully, lingers.

Maybe art is, as one sculptor put it, like a gourmet meal with friends; long after the food is gone, the joy of being together, rejoicing in the moment, stays in some permanent place inside your heart.

Wanna learn more about the Breckenridge International Snow Sculpture Championship and see who won? Here’s a link to the 2022 Guide: Click Here.

If you enjoy this content, please consider subscribing, sharing, and leaving a comment!

4 thoughts on “Tilting at Windmills”