The loss of local newspapers has led to the decline in coverage of the arts and the near extinction of art criticism.

I get it. Papers have had to slim down, cut the fat, make their staff wear many hats. I also understand that reporting on the arts is not exactly hard-hitting journalism. But what really frustrates me is that papers have deputized any old staff writer as “Art Critic.” The result is that the deputized journalist is let loose to wander into the art world with a head full of hubris and a mind lacking true understanding.

A Tale of Two Meanings: Crit-ic (noun)

Definition one:

A person who judges the merits of literary, artistic, or musical works, especially one who does so professionally, as in, “A film critic.”

Similar: commentator, observer, pundit, expert, authority, arbiter, appraiser, analyst.

Definition two:

A person who expresses an unfavorable opinion of something.

Similar: detractor, censurer, attacker, backbiter, vilifier, denigrator, belittler, traducer.

What's in a Name

The biggest problem with the ersatz art critics of the world is that we have come to accept their writing as actual art criticism. It simply isn’t. It’s just one person’s negative opinion, i.e., too much backbiter and not nearly enough authority.

Because knowledge is power, I’m diving into art criticism and what makes this form of writing so valuable and what we’re missing when we don’t get real critics to do this work.

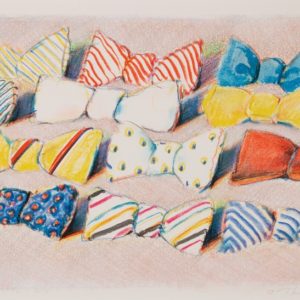

Wayne Thiebaud on Left-handed Compliments

In my 2009 interview with Wayne Thiebaud (1920-2021), I asked about Edward Hopper.

Thiebaud called Hopper a very good painter of whom the art world had done a disservice. He brought up Clement Greenberg–arguably one of the most influential art critics of the 20th century–as an example.

Greenberg says something like this, and it’s an art world kind of way of putting down someone but not too far because they are so well considered by so many people…Greenberg says,

“If Hopper were a better painter, he wouldn’t be such a great artist.”

You give that to a student and the student has to puzzle that out. If you are useful to the student, you make sure that he understands something like that because it’s a central question.

Tennis, Anyone?

Speaking of left-handed compliments, here’s one I recently endured courtesy of the Denver Post’s “art critic” Ray Rinaldi.

The annual Coors Western Art Exhibit has been going on for a good 30 years now and, like a lot of things at the National Western Stock Show, its value comes from the fact that it never really changes.

From here Rinaldi talks about how the show has expanded and diversified…so not stayed the same. Then he writes that the scenery is on repeat, which he follows with a comment stating that the show is staying current by raising issues in the West. It continues in this manner–a nauseating set of left-handed compliments–to the end.

To make matters worse, he sprinkles in his own experience at the exhibit, complete with misspellings and personal meanderings that reflect more about himself and almost nothing about the art.

At one point Rinaldi states that “walking into the show can be a lot like joining a family holiday.” But that’s the extent of his analogy; he never completes the thought beyond suggesting that artists in the show get on his nerves.

He does list the names of artists he’s familiar with–and with whom the art world greatly respects and so he can’t say anything too terrible about, as Thiebaud suggests. But he then goes on to belittle and dismiss everyone else. Sadly, he misinterprets one piece based on its title. This becomes a missed opportunity to delve into the artist and backstory. Not only does he glance over the sculpture but he misidentifies the work as a “hog,” not a coyote. Had Rinaldi looked just a little longer and dug just a little bit further he might have learned not only about art, but about animal behavior that so brilliantly sheds light on human behavior.

Most unfortunately, what we never get from Rinaldi’s writing is a true dialogue about the show, the subject matter, the artists, or the reason for the show.

In other words, his job of guiding us through an exhibit as an authority who is judging its merits never happens. The “review” comes off as petty. In fact, we learn more about Rinaldi’s temperament and inability to extricate himself from an experience than we do about the experience.

Ah, hubris.

Christopher Knight: the Unicorn

So what does good art criticism look like?

There’s a reason Christopher Knight won the Pulitzer Prize in 2020: he’s really good. He brings a depth of knowledge and intimate understanding of the LA art scene from museum to street level. He looks. He digests. He finds meaning. He does this by spending time with art in order to understand the work and make important connections, which actually help us interpret it and, thereby, our world.

Knight shines in his review, “Unicorns are just one of the wild rides in the Getty’s ‘Marvelous Book of Beasts,'” from July 23, 2019, LA Times.

In it, he draws on his vast knowledge of art, history, and Christianity. He kicks off the piece with a bit of insight into the life of Marco Polo who had thought he’d seen a unicorn on his travels, which he wrote about as, “‘Tis a passing ugly beast to look upon.” Of course, Polo hadn’t seen a unicorn, Knight points out, but probably glimpsed a rhino.

Here’s an excerpt:

Unicorns proliferate in the first room of “Book of Beasts: The Bestiary in the Medieval World,” a sumptuous exhibition at the J. Paul Getty Museum. An animal surrogate for Christ’s cleansing purity, unicorns turn up in pictures drawn and painted in the vellum pages of books, carved into the side of an ivory box and the seat of a parade saddle made of bone, woven into a wool and silk tapestry, stained into window glass, hammered into a brass dish, molded to form a ritual water vessel and embroidered into delicate linen cloth.

Knight proceeds to walk us through the exhibit as if we were asked to join him. He regales us with more insights and points out hidden gems along the way. He refers to the curator’s writing and didactic materials, and soon an exhibit that, upon first glance sounded like a stuffy theoretical walk through the Getty archives, has come alive.

But when he takes us to the final room in the exhibit, he offers this:

If only the exhibit had also ended there. Unfortunately, there’s one more room to go, and it misfires.

Wait! What?

I’m hooked on this show because Knight has, through his well-trained lens, offered me a deeper understanding of the exhibit and drawn insightful connections to the human condition. But why did the show misfire? My curiosity is piqued and so I read on.

Seventeen minor specimens of Modern and contemporary art…suddenly catapult us almost 300 years into the future. The exhibition’s closing narrative is disjunctive. What happened between the 17th and 20th centuries is anyone’s guess.

What We Learn

Personally, as a curator, I truly appreciate and am grateful for this section of the review. First and foremost, I want to get better at my work, so hearing why an exhibit misfires is instructional. But too, I know I’ve fallen into the trap of trying to do too much, thinking more is better (which would have been a legitimate critique of the Coors Show).

Knight gives us the reason why this final room of art does exactly the opposite.

Art museums now seem to feel that topical relevance is somehow served by appending recent art to exhibitions otherwise anchored in a historical epoch. Here, reducing the medieval bestiary to a contemporary footnote makes for a listless conclusion to an otherwise strong and compelling show.

I Think I Finally Understand

Rinaldi’s article showed up on one of my social media feeds along with his comment, “I think I finally understand the Coors Show.” If he did finally gain some understanding, he didn’t share it with us.

The late, great art critic, Peter Schjeldahl, in his farewell column to readers of the Village Voice, beautifully addresses the kind of ambivalence Rinaldi stumbles over:

I hazard that about 80 percent of my Voice writing was strongly affirmative in tone, with about 10 percent strongly negative and the same proportion sullenly mixed. Regrets? A few, mostly in the “mixed” category. Critics should shut up when they can’t decide how they feel, not that it’s always possible on a deadline.

Amen to that.

Check out these Critics to read more good writing about art...

Peter Schjeldahl (1942-2022) wrote for The New Yorker for many wonderful years. Here’s a link to “T.C. Cannon’s Blazing Promise,” the review of the 2019 retrospective of Cannon’s work at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian.

Cannon dealt directly with being at once Native and American and, while he was at it, a citizen of the world. He did so in the name of a higher, though difficult and lonely, allegiance. He wrote in a letter from Vietnam, “How thoughtful of God to provide such a life-stream such as art.” -Peter Schjeldahl

Rebecca Solnit is an incredibly prolific writer. Here’s a quote from an article in Cosmo titled, “How I Became a Writer, Historian, and Activist”:

Counter-criticism… seeks to expand the work of art, by connecting it, opening up its meanings, inviting in the possibilities. A great work of criticism can liberate a work of art, to be seen fully, to remain alive, to engage in a conversation that will not ever end but will instead keep feeding the imagination. Not against interpretation, but against confinement, against the killing of the spirit. Such criticism is itself great art. -Rebecca Solnit

Roberta Smith is an art critic for the New York Times. Check out “Roberta Smith on Donald Judd’s ARTnews writings: ‘A Great Template for Art Criticism.’

Everything around you can be analyzed in terms of its visual presence…the great thing about art is that there’s more than you can ever know about, you can’t learn it all. And you’re lucky if you get to spend your lifetime trying to. –Roberta Smith

Michael Kimmelman, critic for the New York Times has several books out. One of my favorites is “Portraits: Talking with Artists at the Met, the Modern, the Louvre, and Elsewhere.” I’m including him here because he’s not the usual critic. Here’s an excerpt from an interview about his book, “The Accidental Masterpiece”:

To keep your eyes open can be remarkably difficult. People typically go to museums and feel that unless they have been told where and how to look, they won’t know what they’re seeing. So they don’t trust themselves to look. No wonder they’re resentful and feel left out. I know the feeling. It took me a while to learn how to open my eyes. Talking with artists helped. I once wrote a book about going around museums with artists and I saw how they looked at the same art differently, through their own perspectives, which proved that there is no single, correct way to look at art. That’s the essence of art—good art—that it refuses to be reducible to one message or idea, so the more you look, the more you can find. It’s a metaphor for life, I think. –Michael Kimmelman

For more insight into the history and genre of art criticism, check out “16 Art Critics Who Changed the Way We Look at Art,” in Artsy.

Want to read that entire Wayne Thiebaud interview? Here ya go! Enjoy.

Wayne Thiebaud, part one

I interviewed Wayne Thiebaud on March 16, 2009, at the LaBaron’s Fine Art Gallery, in Sacramento, California. It was a drizzly morning but the gallery’s

Wayne Thiebaud, Part Two

I interviewed Wayne Thiebaud on March 16, 2009, at the LaBaron’s Fine Art Gallery, in Sacramento, California. It was a drizzly morning but the gallery’s

Wayne Theibaud, Part Three

I interviewed Wayne Thiebaud on March 16, 2009, at the LaBaron’s Fine Art Gallery, in Sacramento, California. It was a drizzly morning but the gallery’s

8 thoughts on “The Death of Art Criticism”