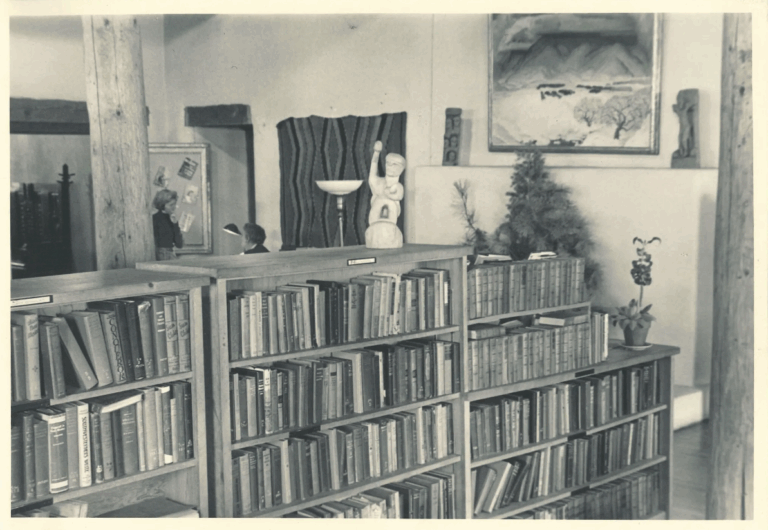

In 1985, the Harwood Foundation, in Taos, New Mexico, now the Harwood Museum of Art, served a dual purpose as the town’s museum and library. Throughout the adobe building’s two floors, paintings by Taos Society artists hung beneath the vigas on lime washed plaster walls. Librarian Tracy McCallum’s desk was situated on the first floor with a clear sightline to the Harwood’s entrance. On a mild spring afternoon in March, he was there, at his desk, when a woman requested a wheelchair and his assistance getting up the old elevator to the second floor. McCallum obliged, showed her around and then helped her back downstairs on the elevator. He then returned to his desk. There were many visitors that day, none of whom McCallum later recalled as standing out, except for one: the man in the long black raincoat.

Near closing time, David Caffey, the Harwood’s director at the time, walked upstairs for a final check, stepped into the gallery and saw immediately that there, on the north wall, was a blank space where a painting had been. He turned around and saw, to the south, the bottom leg of the frame still stuck to the wall, but no painting.

In the police report, McCallum recalled how the woman in the wheelchair needed his help and then later, how an Anglo male approximately 40 to 50 years old, slightly bald, approximately 5’8” wearing a long black raincoat looked at him then quickly turned and exited the museum. That man stood out, McCallum said, because he walked with his hands in his coat pockets, as if he were holding something underneath.

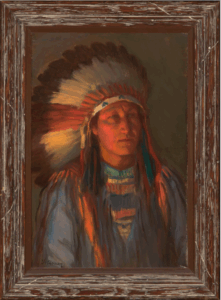

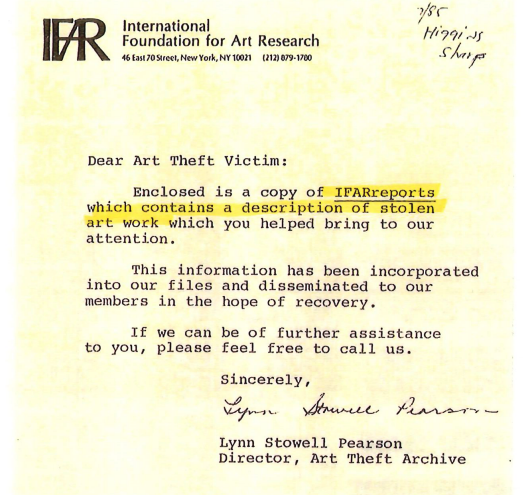

Harwood curator David Witt was not in his office that day; ironically, he was in Santa Fe attending a seminar on museum security. Witt didn’t learn of the theft until he got back that evening. How could someone walk in and take two works of art off the walls in broad daylight, and no one noticed? Witt notified the FBI the next day, and contacted galleries, dealers, and art associations letting them know of the theft. For years after, Witt scanned auction catalogues in hopes that “Oklahoma Cheyenne,” c. 1915 by Joseph Sharp and “Aspens,” c. 1932 by Victor Higgins would turn up, but they never did, at least, not during his tenure.

Six months after the Sharp and Higgins were stolen, Willem de Kooning’s “Woman-Ocher” was cut out of its frame where it hung in the University of Arizona Museum of Art gallery and smuggled out of the museum in broad daylight. It was the day after Thanksgiving and the museum was quiet, except for the woman who chatted with the staff and the man in a black raincoat.

Art Theft and the Black Market

It is estimated that some 50,000 works of art are stolen each year fueling the nearly $8 billion black market for stolen art. You might think that these crimes are done for financial gain—and many are. But Robert Wittman, founder of the FBI Art Crime Team, believes there are three types of art thieves. The first commit a theft of opportunity; basically, they’re shoplifters. The second kind steals for money, and these thieves make up the lion’s share. But then there are the people who steal for themselves.

“They feel like, since they care about it, they are entitled to have these pieces,” he said in the documentary, The Thief Collector. “They’re the most dangerous. And they’re the hardest to capture.” Wittman says these people are so difficult to track down because once they have the art, they hide it and keep it purely for their own enjoyment. “And those things,” he says, “go away for many years before they come back.”

But I Didn't Know

“Nemo dat quod non habet” is a handy Latin phrase you might want to remember when buying art at auction or from someone you don’t know all that well, like the guy offering a great deal on a Rembrandt in the trunk of his car. Also known as the “Nemo dat” rule, it translates to “no one can give what they do not have.” In other words, you can’t own stolen art no matter how much you pay for it.

Don’t panic if you unwittingly buy something that was stolen, which, given the staggering number of objects stolen each year, might be easier than you think. You’re not in trouble unless, however, you refuse to return the stolen goods. This falls under the “Demand and Refusal Rule.” When and how this rule is applied can vary from state to state, but essentially, the clock on returning stolen art starts when the true owner discovers its whereabouts.

As you might expect, there are lots of gray areas that influence the final outcome in these cases. For example, did the person whose art was stolen file a police report? Did they notify the FBI, and did they list the stolen art on international loss registries?

Sounding the Alarm

When the Sharp and Higgins were pilfered from the Harwood, Juniper Leherissey, executive director of the museum, says, “David Witt used his extensive list of galleries, museums, and other art entities. There was a large effort within our regional network of museums and galleries to notify them of the lost works, as well as all the formal channels: letters to Interpol, the art loss registry, and others, so we have all that documentation.”

But that was forty years ago, and even Leherissey who grew up in Taos, wasn’t aware that among the 6,500 works of art in the Harwood collection, two were missing. And, interestingly, the insurance company the museum worked with back then has gone out of business. But still, the trail had been established.

As collectors, you may be wondering what happens if you do buy stolen art, pay for it, and then, weeks or even years later, the FBI gives you a call. We talk a lot about provenance in this column. Here’s a nightmare scenario that is an excellent reason why collectors need to take provenance seriously and double check anything that gives you pause. Look for records of who the original owner was and all the subsequent owners, museum exhibitions, etc., that provide important assurances that the piece you’re interested in can be linked to honest brokers.

Beyond that, only work with honest dealers and auction houses. These folks should be looking out for you by verifying provenance, though there are plenty of examples where dubious provenance was either glossed over or blatantly covered up.

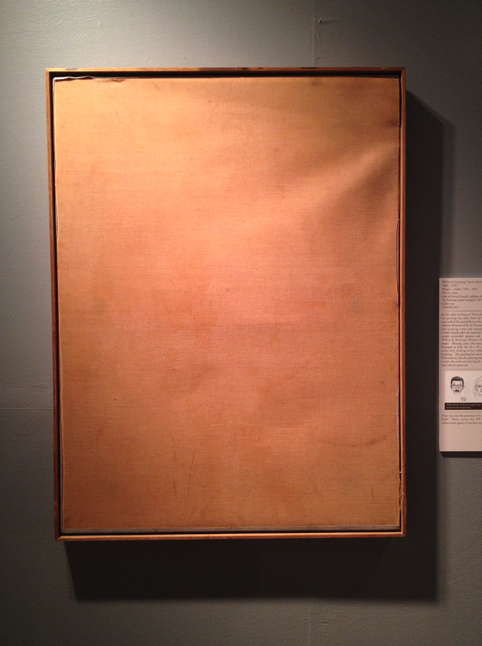

A Strange Email, an Amateur Sleuth, and the Documentary

On the thirtieth anniversary of the theft of the de Kooning, the University of Arizona Art Museum curated an exhibit that featured the empty frame from which the painting was sliced out. Wall text gave details of the heist and publicity of the show renewed interest in the crime, including that of amateur sleuth, Lou Schacter, a retired corporate consultant who enjoyed researching art crimes. He was intrigued by the de Kooning heist and visited the museum in 2014, thinking he would dive into that crime soon. The de Kooning, however, surfaced before Schacter got to it.

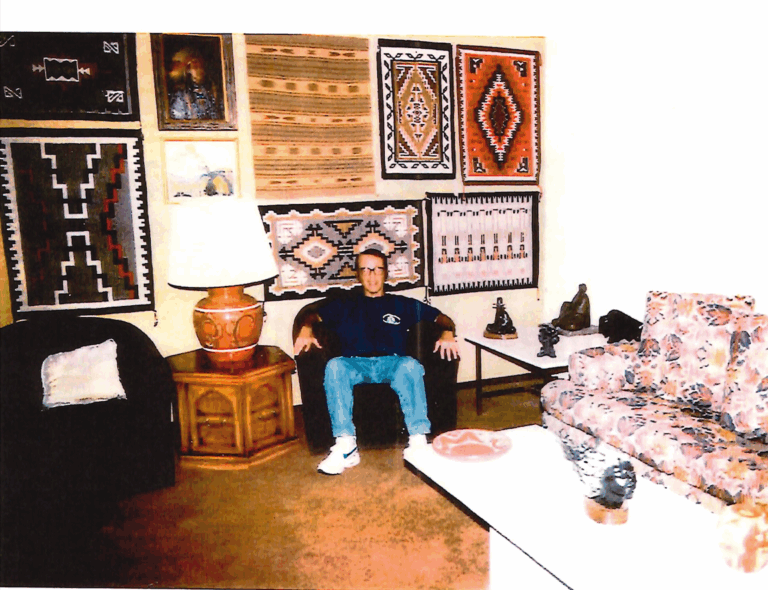

Enter Rita and Jerome Alter, former schoolteachers who lived a quiet life in Cliff, New Mexico. They owned a modest home and spent their retirement years traveling to far flung places. At family gatherings, they shared photos and stories of their latest trips, and in their home, they displayed mementos such as weavings, small sculptures, and paintings collected along the way. Jerome died in 2012; Rita in 2017. Their estate was left to relatives who, overwhelmed by the volume of things the couple owned, decided to donate some of it to a local garden club and sell the rest, part and parcel, to an antique shop up the road in Silver City, New Mexico. After going through the mostly Southwestern objects donated to them, the head of the garden club started to think some of those things might have real value; she contacted the Scottsdale Art Auction and consigned a number of paintings and sculptures to them for a sale in 2018. The painting the garden club didn’t want, however, was a strange and disturbing piece that hung in the Alter’s bedroom, behind a door—that went to the antiques shop.

Hey, Is That Real?

From here, the story takes an amazing turn. The Manzanita Ridge Furniture and Antiques store owners paid a little more than $2,000 for the estate. When they began sorting through the objects they bought sight unseen, they came upon the painting behind the Alter’s bedroom door. David Van Auker didn’t know what it was and so, brought it back to the antique shop and leaned it against a wall. A local walked in, took one look at it and asked Van Auker if it was real—was it a real de Kooning?

A quick Google search turned up all Van Auker needed to know. He called the University of Arizona Museum of Art and spoke to curator Olivia Miller, telling her he wasn’t crazy, but he believed he found their painting, “Woman-Ochre.” “I’ll never forget that moment,” Miller said in an interview for The Thief Collector. “I asked him to email me photos of the painting detailing the signature. Every time we opened a photo, we said, how do we get to Silver City? This is the painting!”

After contacting the University police department, however, the curators were told not to talk to Van Auker anymore, that they would take it from there. So, they stopped responding to Van Auker’s calls and texts. In Silver City, however, word of the de Kooning had spread. “People were coming in saying we want to see the de Kooning,” Van Auker said of the painting that he learned was estimated to be worth more than $100 million. Unnerved, he took the painting home and hid it behind his sofa. He then pulled a couple guns from his gun safe. “People are killed for less than a hundred million dollar painting,” Rich Johnson, Van Auker’s business partner said.

For the Record

The antiques dealers just wanted the de Kooning gone. At the museum, the curators too were panicking. What if this Van Auker guy changed his mind and sold the painting out from under them. Finaly, van Auker left a voicemail for Miller saying that all he wanted was for the painting to go back to the museum and that he was freaking out: “Somebody,” he said, “might cut my throat for that painting. Keep this on record: I don’t want to hold it hostage; I don’t want a ransom. I want you to have the painting back.”

To the great relief of everyone, the museum staff was finally given permission to get the de Kooning. It had sustained considerable damage from being sliced out of its frame, rolled, and smuggled out under the thief’s coat and was sent to senior conservators at the Getty Museum for restoration. Happily, it’s now back home at the museum and on display, once again.

Where There's Smoke

Remember our amateur art sleuth, Lou Schacter? He had a hunch that “Woman-Ochre” was not the only stolen art in the Alter’s home. He reached out to Van Auker and asked what he thought. In a story for Medium, Schacter recounts his conversation with Van Auker who told him the FBI said that none of the works sold at auction were listed in its stolen art database. That didn’t mean they weren’t stolen.

Schacter wondered about three pieces in particular that the garden club sent to the Scottsdale Auction. In the documentary The Thief Collector, there were photos of the interior of the Alter’s home and an interview with a woman from the garden club who says there were paintings by Higgins and Sharp, as well as sculptures by Remington, Allan Houser, and an RC Gorman.

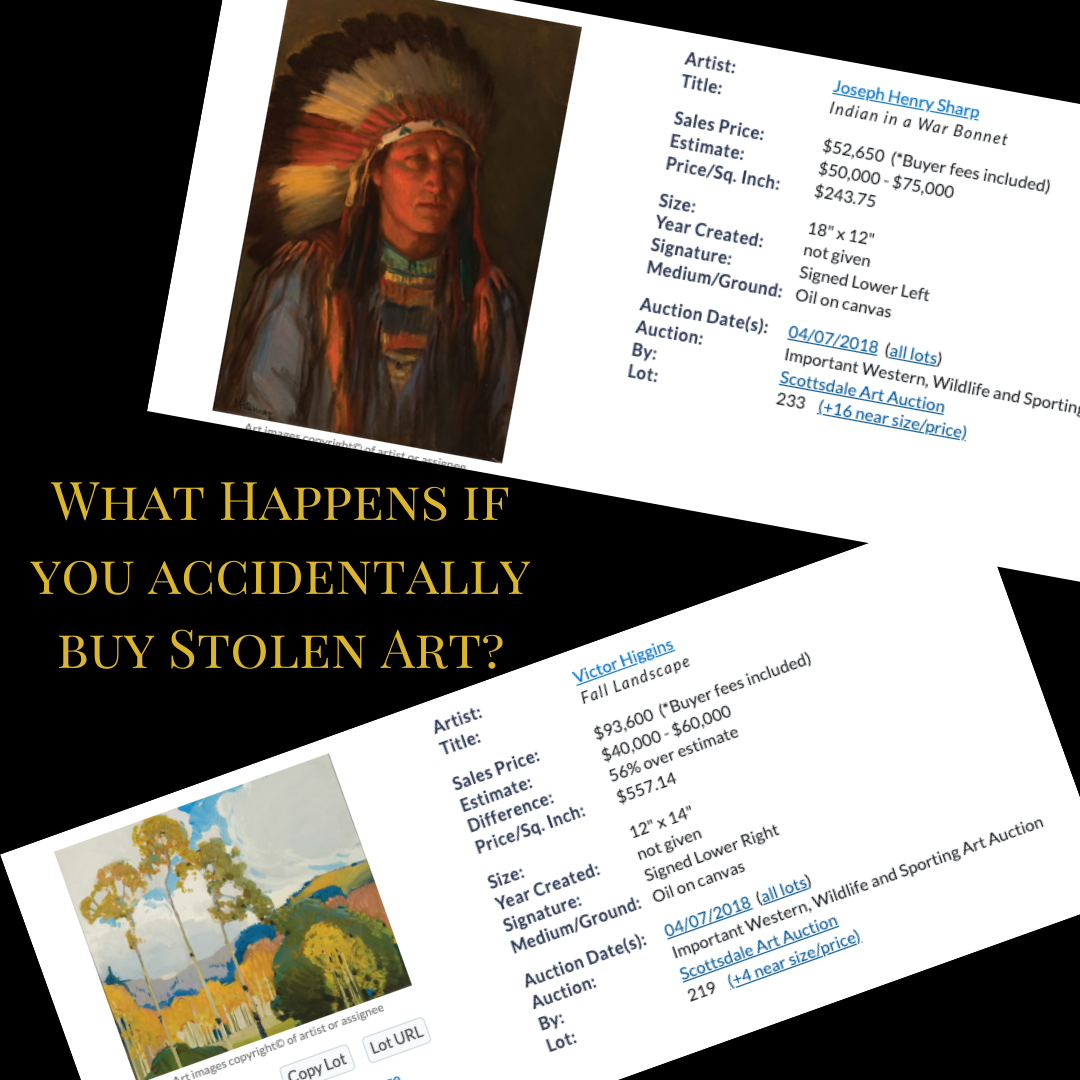

Using photos from the documentary, Schacter started searching auction records looking for matches. That’s when he discovered two paintings sold through the Scottsdale Auction on April 7, 2018, that looked like an exact match to the pieces stolen from the Harwood in March 1985.

Schacter reached out to Leherissey to let her know he thought a Sharp and a Hennings that were auctioned in 2018 belonged to the Harwood. “That’s really the first time it came to my attention,” Leherissey says. “That was December of 2023. I reached out to my collections manager and was like, is this for real?” Sure enough, her manager found the file on the stolen paintings and the documentation from forty years ago.

The Harwood team gathered their provenance for the paintings and created a dossier, then they contacted the FBI’s art crimes unit to ask if they would take the case. “The FBI decides whether to take a case based on various factors,” Leherissey says. “Luckily they did take ours, otherwise I don’t even know how we would’ve managed. We would’ve had to get lawyers involved, subpoena people, identify the buyers, and figure out how to secure the works back. Without the FBI’s support, it would have been very challenging.”

Home Again

Thanks to the FBI’s involvement, the Higgins and Sharp are now back at the Harwood, and in great condition. As for the buyers, one who paid $52,650 for the Sharp and the other who paid $93,600 for the Higgins, Leherissey doesn’t know if they got their money back from the Scottsdale Art Auction. “A collector who inadvertently purchases a stolen artwork may get some compensation,” Leherissey believes but is quick to add that auction houses have a lot of legal protections in place for situations like this. “It doesn’t sound like the auction house was ready to pay buyers back the money that they spent on the works.”

When I called to discuss this with the Scottsdale Art Auction I was told there is an ongoing investigation and that they cannot comment at this time.

These days the Harwood’s security systems are greatly enhanced and include cameras, sensors, alarms, and gallery guards—all things we patrons hardly notice anymore. But it’s amazing to think back to all that art hanging on walls in the Taos library that anyone could walk up to without being shooed back or set off an alarm. When asked if she thought the 1985 Harwood theft was a test run, Leherissey says, “Oh, maybe they’d done it a million times before; they seemed to have their game down. They would even put on costumes. But yes, it was very intentional. They were trying to steal from small organizations that might be more vulnerable.” She even wonders about other objects shown in the documentary that wound up at auction. “There was a Remington, an Allen Hauser, and an RC Gorman—three bronzes. We had the RC Gorman Gallery in Taos at that time. Did they just walk up the street and take the next thing? We don’t know how many other things they stole. What we do know is that they funded a lifestyle that was not sustainable on their apparent incomes.”

For Leherissey, getting their paintings back is more than just a mystery solved. “We have such a rich art community. Both of these artists were so much a part of the Taos community and the Harwood. Victor Higgins was on our founding board, and he gifted some of the most significant of his works to us directly. Those paintings not only came home to us, but the artists are home now, too.”

Stolen Art Resources

If you are a victim of an art theft, start by calling the local police. If the crime is within FBI jurisdiction—the object has traveled across state lines or was stolen from a museum—then you will contact the FBI, and a local FBI Art Crime Team member will begin the investigation.

According to the Santa Fe Art Crimes bureau, they recover paintings by following investigative leads and rely on the cooperation of all parties involved to be able to recover and return the paintings, as was the case with the Harwood Museum paintings.

As a collector, the FBI advises, protecting your own art starts with keeping an inventory of your valuables. To safeguard yourself against purchasing stolen art we recommend performing due diligence on anything you are wanting to buy, only go through reputable dealers, and always check the provenance.”

We encourage the public to review the National Stolen Art File at ArtCrimes.fbi.gov and if anyone has any information about any work listed, please report to 1-800-Call-FBI or tips.fbi.gov

-Statements attributable to the FBI Albuquerque Field Office

Additional information:

https://www.fbi.gov/investigate/violent-crime/art-crime

https://www.fbi.gov/video-repository/newss-fbi-art-theft-program/view

4 thoughts on “The Art Heist”