This January, I had the privilege of interviewing the inimitable Jaune Quick-to-See Smith. As painter, printmaker, collage and installation artist, curator, lecturer, and political activist, her contributions to and influence on modern art in America have been astounding.

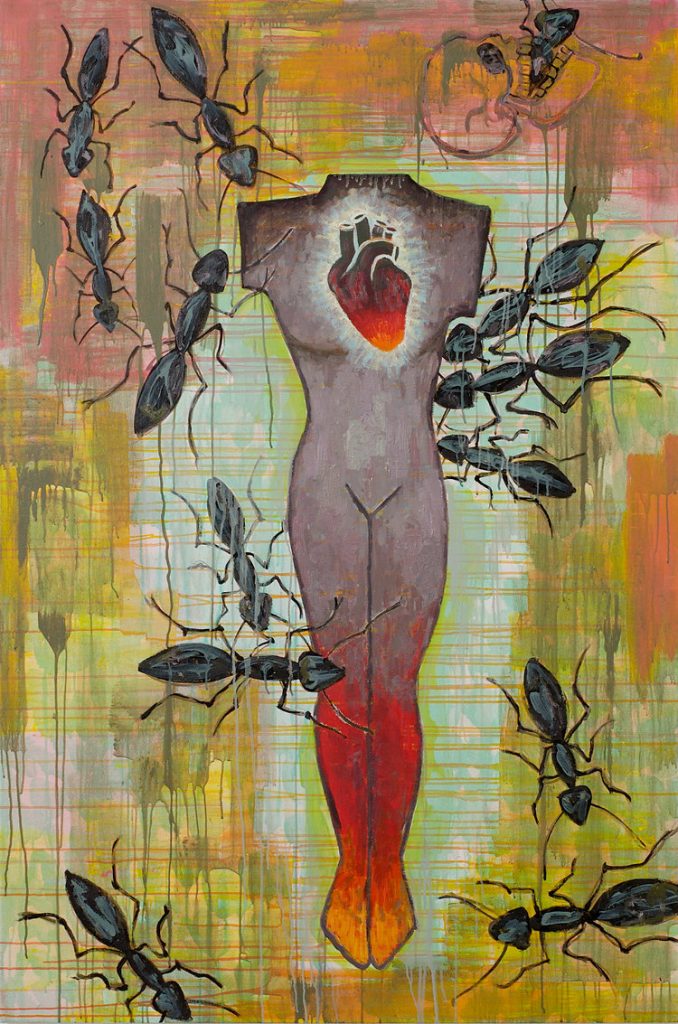

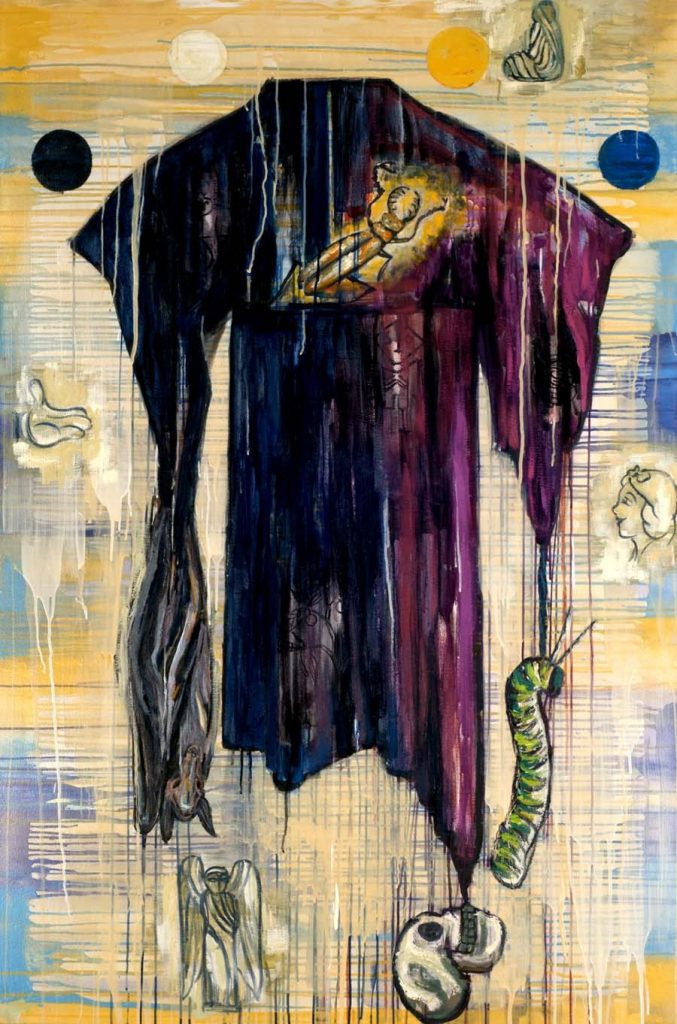

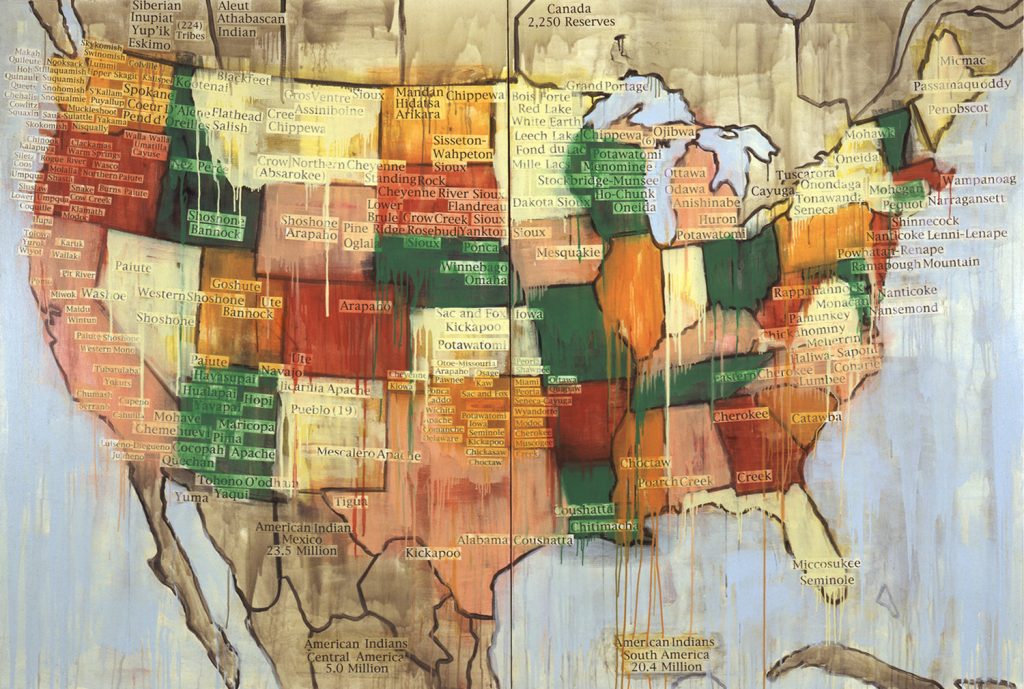

It has been said that Smith, who turned 80 this year, speaks two languages: that of the modernist and that of the Native American. As a modernist, she captivates with color, design, fluidity of mark-making, and concept—the common language of the artist. But it is her vast knowledge of art history that allows her to use this language as the basis upon which she inscribes her personal history and culture.

This interview was the basis for an article appearing in the August/September 2020 issue of Western Art & Architecture.

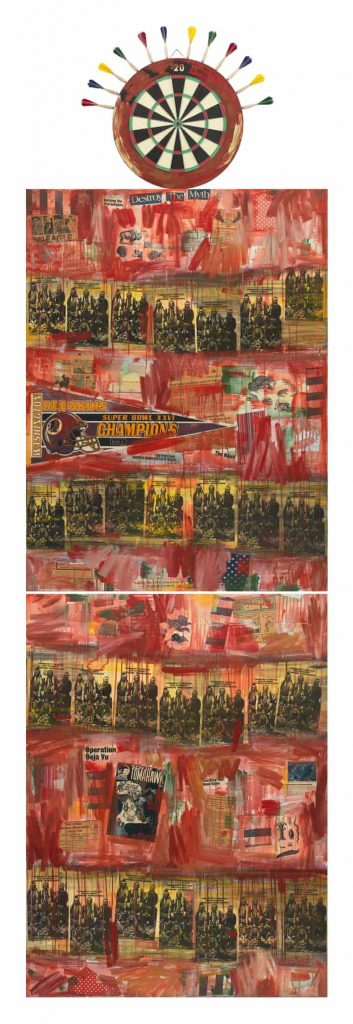

NOTE: On June 23, the National Gallery of Art issued a press release announcing the acquisition of I See Red: Target (1992) by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, the first painting by a Native American artist to enter the collection.

Wait…what?!

Interview, January 12, 2020

RF: It’s hard to walk the line between creating art that matters, that says something or has a social impact versus creating art for the market. You have, in my mind, consistently brought forth important and poignant works, many that have strong meaning and offer social commentaries. I’d love for you to talk about the importance of art and artists, especially today, to speak out but also, about how you’ve been able to create works that are socially challenging and widely accepted.

JS: Wow what a question! Thank you for those kind words. I always try to walk that line between creating attractive or interesting work yet with strong social commentary and always with humor or maybe better words would be satire or irony. Nearly each painting, print or drawing makes a comment on something such as war, social justice, the environment, women’s rights, animal rights, racism, Native history, etc. I know that doesn’t sound like funny stuff, but comedians usually deal with these ideas too, so did painters like Bosch. I certainly didn’t invent this way of working, Picasso’s Guernica, Goya’s Los Caprichos, James Ensor’s work, Frida Kahlo and Louise Bourgeois plus so many more are role models for me. They demonstrate that yes, an artist can make an engaging painting that has depth of meaning but oh, some funny schtick too.

RF: Would you talk about the concept of the trickster and your life playing the part of the trickster? I’m curious about how that role has changed and/or evolved over the course of your career.

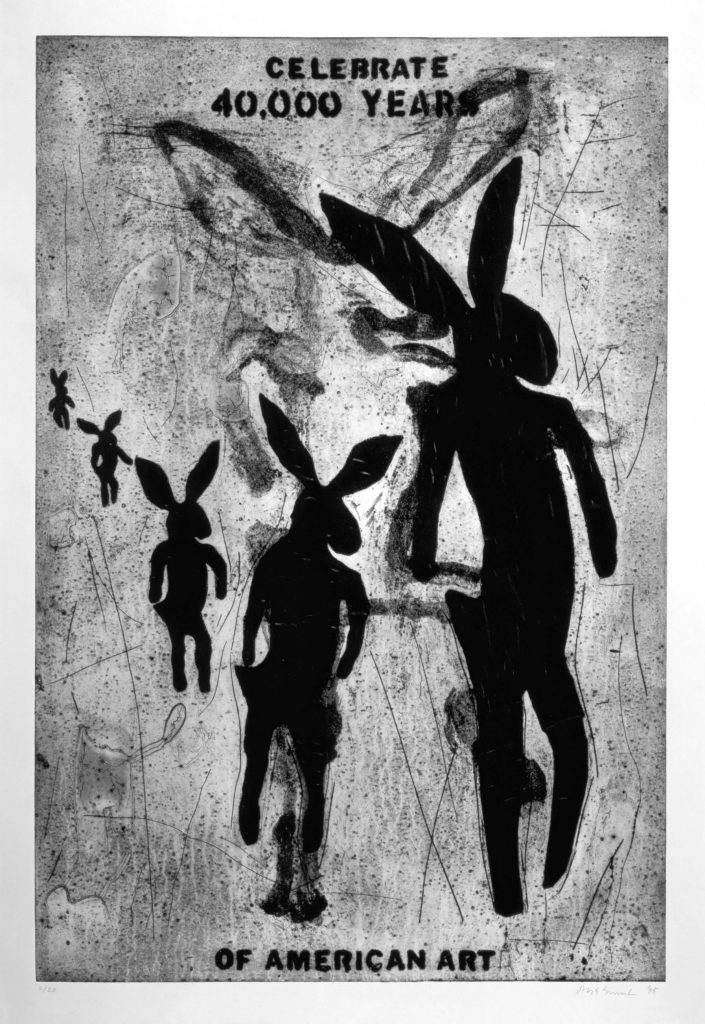

JS: Tricksterism can be part of making art, writing or doing theater. The creator, inventor, satirist must show the flip side of things. They turn things upside down in order to lampoon the immorality or insincerity of politicians, priests or heads of governments or show the human condition. Shakespeare, Krazy Kat, the Muppets, Stephen Colbert, Wile E. Coyote, Will Rogers, Bugs Bunny all show us human beings at their worst and maybe their best too. Wile E. Coyote and Bugs Bunny are surely taken from our traditional Native American creation and teaching stories. They mock greediness, failures, shortcomings and narcissism—the foibles of human life. They hold up a mirror for we humans to see ourselves, in the flesh, warts and all.

Some of us spend a lot of time and money in beautifying ourselves on the outside and no time fixing what ails us on the inside, our insensitivity, our lack of kindness and our inability to share, our neediness and greediness, lack of truthfulness.

Theater, most writing, and tons of art would have nothing to say without caricature, ridicule and parody. This is what makes great art last through the ages. Hieronymus Bosch and his Garden of Earthly Delights in 1516 is one of the best examples I can think of with his shocking scenes of humans in sexual entanglement and surreal images that are so so modern. And, of course, Shakespeare’s plays will last through the ages, no matter the archaic English, it’s because he is dealing with the human condition.

One of the most incredibly beautiful films ever made, where each frame becomes a painting, is the Kurosawa film Ran based on Shakespeare’s King Lear. This is such a timeless story I can see that it is fitting for today, oh how it is fitting for today.

One summer I grounded my daughter for a week when she was 12 and as part of her grounding, I insisted she watch foreign films with her dad and me every evening. Some of them were Chinese Opera, which told stories about people’s sad plight in life when they made bad choices. At first my daughter was unhappy about her sad plight, but as the week wore on, she looked forward to our evening’s viewing of a new foreign film. In her 40’s now she often recalls with delight the story of that week in her childhood and how she changed her mind from thinking she was being abused to realizing that she was being enriched.

RF: At this point in your career, are you feeling hopeful for today’s younger Native American artists? What needs to happen, in your opinion, to help advance the cause to getting NA artists’ work brought to the forefront and to get their work in museums and spotlighted in collections?

JS: Oh yes, there are definitely new rules, museums are actually seeking Native artists and especially the young ones, beautiful, brainy, articulate, well-educated, well-traveled. It’s a new era, partly social media should receive credit. Partly it’s because these young talented artists, including my son Neal Ambrose-Smith who is Chair of the Art Department at the Institute of American Indian Art, our prestigious Indian college in Santa Fe, these artists are easier to find due to their websites. They are more savvy than my generation and their work is more sophisticated when they arrive on the art scene.

We still don’t have the plethora of private collectors that African American and Latinx artists have and certainly not from within the Native community. It’s about economics and we don’t yet have Native CEO’s in the corporate world, although our CEO’s might be Tribal Chairmen or Arena Directors of a pow wow, but those jobs don’t pay that well.

We also don’t have Indian peoples on the boards of museums which could help direct the museum collections with more Native inclusivity. Our tribal peoples serve on boards at our Tribal Colleges which have no contact with the museum world. It’s a fact of life that we live in two different worlds with differing agendas, ours is about Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs and we stand at a survival level, there’s no room in that budget for purchasing art. We use our art for trade goods and trade with each other, we also give it away to fundraisers for scholarships, for food pantries and to raise money amongst ourselves for helping a tribal member whose house may have burned down because, of course, few have any insurance. That’s a luxury for white people. Americans don’t know much about subsistence living, except those of us who’ve lived in that world. When I see homeless people I cross myself and say: “There but for the grace of the Creator go I.”

RF: A byproduct of the #MeToo movement has helped, I think, call attention to the lack of women represented in museums (and galleries and magazines and…). Do you see any progress for women and, in particular, Native American woman?

JS: As Native women, our situation is somewhat the same as the “Me Too” movement but also somewhat different in that “Me Too” is not about missing and murdered women.

We, in the Native community have a real genocide going on, especially on our Northern border as well as our Southern border and across the country on our reservations and in our Indian towns. Indian women go missing from parking lots at grocery stores, gas stations or walking to and from work. Up to now police departments have ignored the pleas of the Native communities. We’ve been doing art shows, news interviews, public shout outs to garner attention for this horrific situation in our communities. So again, we fall off the charts when it comes to anything like being featured in magazines, museums or galleries; Native women are still not recognized in these arenas.

RF: Your work is in many prominent museums and collections, and you’ve created intriguing installations. Looking back over your career, what do you think your legacy will be?

JS: Thank you for those kind words. I would say, yes, my work is featured in some prominent museum collections but I wouldn’t say any prominent private collections, I’m not there yet. I think my legacy might be that I led a purposeful life and I moved the needle of Native recognition in the arts maybe a skosh.

RF: Speaking of those major works, would you talk about one or two that were seminal in your career? Any major works/installation that you’re working on now?

JS: Artists generally don’t get to decide their seminal works, but museum curators, writers and other elite, as well as, scholars determine that. Often, you’ll see in an artist’s personal collection some work that is quite different from the work in public collections. It might seem unfinished or scruffy—and we ask “why would they hang onto that thing?” Well, they feed off it, it speaks to them, is a muse for them.

I’m talking about yours truly here. So yeah, I have a painting that is littered with divots of collage, some bread wrappers and wallpaper and signage that tells us to learn Spanish, “Get Ready, Get Set, Grow”—oh yeah, that is a turn on for me. I have lots of paintings that I like not because I think they have great beauty or composition but no, I like them because I have some small secret message or image that only the very discerning will ever notice and it’s my way of leaving a message for when we’re all floating in the solar system and my painting is headed to Mars to give a message to some space personage out there because Earthlings didn’t take notice and trashed the place making it unlivable.

RF: Finally, which artists are you most excited about today and/or feel have been overlooked?

JS: The artists I’m most excited about are all Native American, young and old, I want them all to make art because, as my German friend Dorothee Peiper has said for years, “Native American art has so much to teach the world.”

RF: Let’s hope we start listening.

For further reading about I See Red: Target, CLICK here for the article in The Guardian.

Click here to visit Jaune Quick-to-See Smith‘s website.