I have to admit, I’m not a fan of the old art collecting adage, “Buy what you love.”

It’s a little too capricious for me. I mean, really, how do you know what you love? Have you consider absolutely everything that the art world has to offer? Besides that, how do you know what you love is any good? Or worth the asking price? Or will hold its value?

When it comes to making an art purchase, I put three basic rules ahead of buying what I love:

- Get to know the artist

- Buy the original

- Walk away

Once I figure out this stuff, buying what I love just happens naturally. Here’s how I do it.

Understanding Art & Creator Are Inextricable

As a curator, I get to call artists all the time and dive into deep, esoteric conversations that involve learning about their recent work, where it’s headed, how sales are going, what they’re struggling with, stuff like that.

Not your normal day? I get it. You can, of course, learn a lot online; that’s how I usually start. When I dive into a search, I am looking for specific things, which I’ll go over next, but I should also tell you, I rarely base curatorial decisions–for a show or my own collection–on this alone.

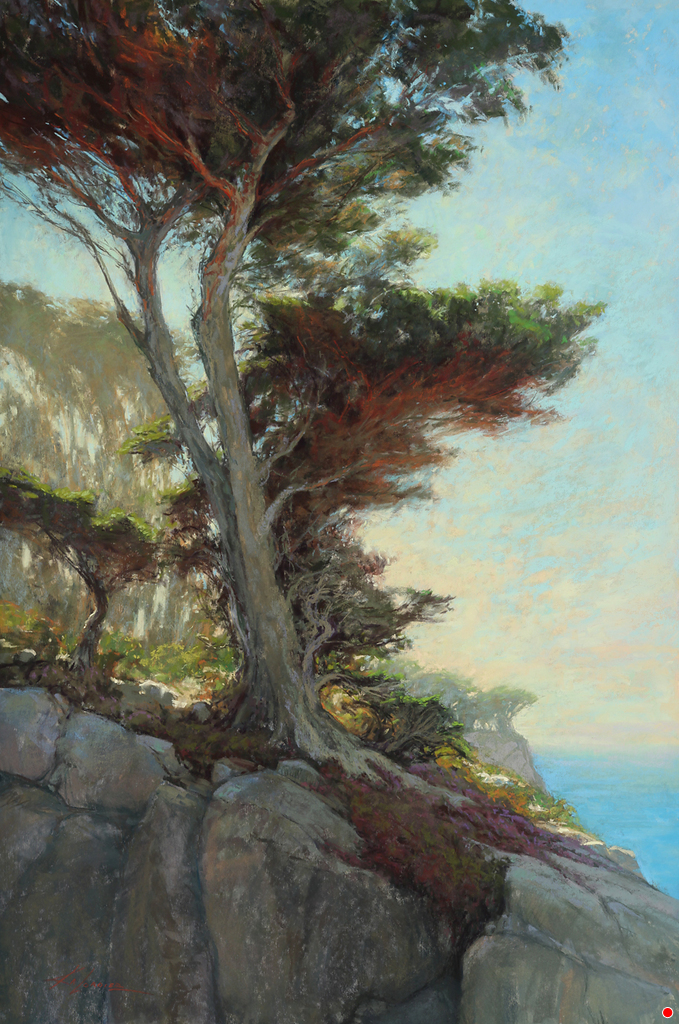

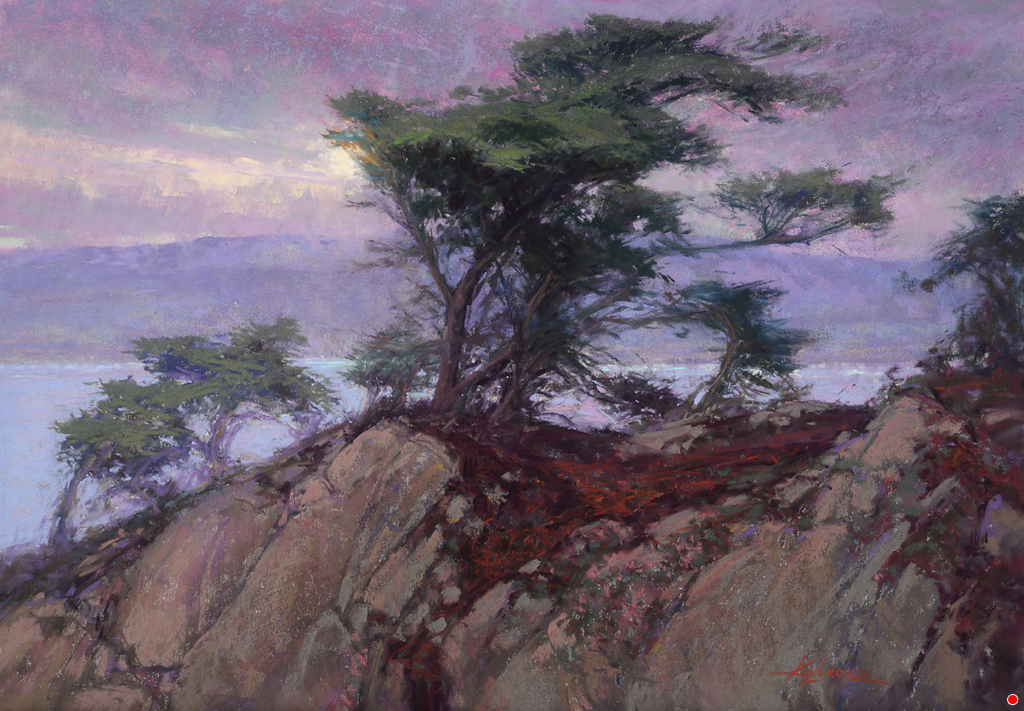

Listening for Intention: Influences

Full disclosure, I don’t care if an artist graduated from art school, and you shouldn’t either. When I’m Googling artist websites and reading through their “About” page and CV, what I want to know is who they studied with, either in art school, workshops, mentorships, or private classes. (I’ve met a couple self-proclaimed autodidacts, but I’m pretty sure even they had influences.) The thing about training versus an art degree is simply this: I’m looking to understand influences on the artist, whether one seminal comment by a master triggered a turning point, or a geology professor instilled an awe of evolutionary forces at play in the land, which then led to the pursuit of an artist’s singular vision of man’s place in the cosmos. It’s all good. It’s all relevant. And it all plays into the unique aspects separating a good craftsman from a true artist.

Commitment

I probably weigh artist websites, CVs and “About” page text differently than most. I’m reading between the lines, looking for direction, trajectory, a level of professionalism.

Ultimately, I’m looking to see if the artist is in it for the long haul. And it is a long haul. Making it as an artist is tough and unforgiving and filled with rejection. Does the artist I’m looking into have what it takes to keep going–mainly because they can’t fathom any other life–or are they going to quit when things get tough? And things will get tough.

Authenticity

This is a tough one to uncover and, frankly, it’s not something a newcomer to the art world will intrinsically know. After 30 years, I have seen a lot of art and a lot of copy-cats. I’ve called a few out on it and firmly advise collectors to avoid the inauthentic.

I can’t stress this enough: creating original art is extremely difficult. It takes a level of training and perseverance that most people are unwilling to give. For me, to feel comfortable when adding an artist to a show–essentially saying I’ve vetted this artist for you, Collector–the artist needs to have his or her own voice. (I talk about this in my blog “On Voice.”)

There’s nothing new under the sun, this is true. But an artist who is responding to current issues, whether external or internal, and using his or her own voice to do so, is at least trying to add something important to the conversation. Consider how Jazz musicians have riffed off the work of Beethoven, who’s sonatas were based on a structure that he manipulated and ultimately transformed so radically that he changed the course of music. (Check out this wonderful article from the Harvard Gazette about Beethoven’s wide ranging influence.)

Developing Your Eye

I’ve come to believe that collecting art–or probably anything, for that matter–is a bit of an addiction. At least it is for me.

When I first started collecting, I didn’t have two nickels to rub together, but still I knew I wanted to own original art. I was working at a gallery and met so many artists who were gracious and answered all my crazy questions.

I hit the street fairs (the Art Students League Summer Art Market in Denver is a favorite). And I bought directly from artists when they, too, were starting out.

Over the years, working in galleries, going to openings, lectures, and artist studios and just listening to the conversations, arguments and critiques they gave each other taught me to really “hear” an artist’s voice, literally and metaphorically.

I still do all these things to this day. In fact, I would say that buying art on a non-existent budget taught me how to find promising emerging artists. It’s become my niche in art curation.

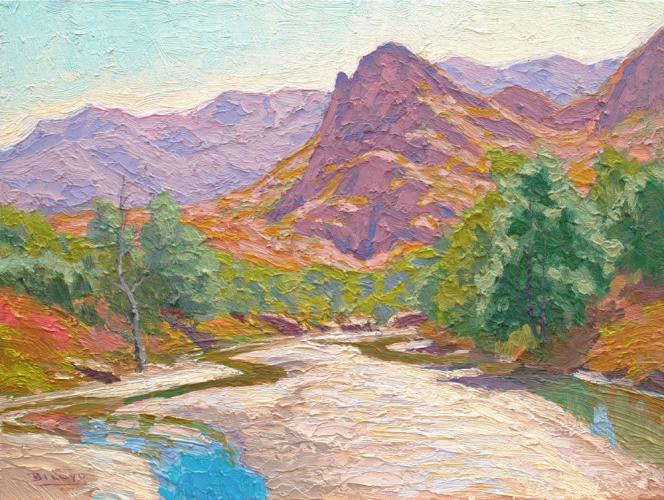

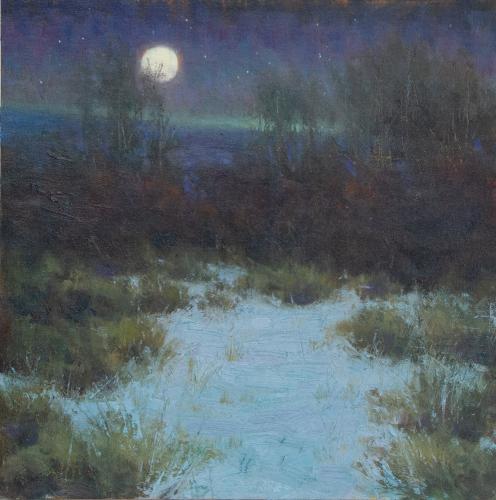

Some of the artists I collected early in their careers include Ron Hicks, who was working days at PrimeStar and painting at night, David Grossmann and Maeve Eichelberger, two artists whose work I bought when they were fresh out of art school. I can’t afford their work these days, but, yes, that means my purchases have gone up in value…not that I would sell anything I’ve own.

What I’m getting at is, you may think you can’t afford original art but you can. You just have to know where to look. And, do a little homework when you do spot an interesting artist. Besides art fairs, most every city has a selection of co-op galleries that feature up-and-coming artists, and even established galleries carry emerging artists they believe are promising. Works on paper–hand-pulled prints, that is (not giclees, more on this in my next blog)–are usually very affordable, too. Also, watch for pop-up shows–you’ll learn about them if you start following artists you like on social media–that feature work from relatively unknown artists.

The Key to Buying Unknown or Emerging Artists?

Educate yourself and develop your eye. There are lots of people out in the art world who would love to help from curators to gallerists and even artists. Just know that if you work with a consultant, you will have to pay them but consider it an investment in your collecting education (think of the money you’ll save by not buying art you regret and that doesn’t hold its value).

When Taking a Step Back Is Critical

I feel a little funny advising this because I am in the art sales business but, well, it’s truly what I do. I rarely impulse buy anything.

In the art biz, our secret opening night formula is:

crowds + booze + artists + red dots = killer sale

Crowds create the atmosphere and buzz. Booze, well, you know all about booze and impulse decisions. Artists, oh, yes, artists are just so much fun, even the grumpy ones! And those red dots… As soon as they start popping up on wall tags, it’s like firing the starting gun, may the best man win!

Why I Walk Away

I’m around art all the time, in and out of studios, talking to artists and seeing the latest painting, hot off the easel. I can always step back and think on things for a few days before deciding.

For those who don’t have that kind of access, here’s what I’m suggesting you do. Go to previews. Take your time. Walk through the gallery in a clockwise fashion then go back through counter-clockwise. If you go with a friend or significant other, separate and walk in opposite directions, snap pics on your phone of the things you like so you can compare notes later. Find the curator, director or go with an artist whose opinion you trust, and ask lots of questions.

Then walk away. Sleep on it. If you wake in the morning thinking of a work of art–in my case, I will be obsessing about it–then you should get it. If you do this, you can avoid some of the pressure-cooker psychology of opening night and bid or buy with certainty.

I would love to know your process for collecting. Artists who read my blog, please chime in on how you’ve help collectors purchase art, too–I know many of you have!

NOTE: As I wrote in the last blog, Art Buying Etiquette 101, do NOT ask to buy directly from the artist, if you saw the work at a show or gallery. You are putting the artist in a terrible spot and jeopardizing their career. If you call the artist directly, don’t lie about where you saw their art; this is very unprofessional and makes artists uneasy and untrusting of you. In most cases, you’re not going to save money going to them directly anyway. Work with the gallery or show. If you want a discount, discuss with the dealer. Leave the artist out of it.