Miss Manners: What to tell artist friends, besides ‘That’s pretty!’

“It’s not hard to please artists–or any other creative people–with compliments. Any enthusiastic generality will do. And while you are not there as an art critic, Miss Manners has a kind remark even if you really hate the work: “You must be so proud.”

Um, wait…what?!

OK, Miss Manners, step aside. Here’s some actual etiquette for talking to and working with artists.

You’re welcome.

GALLERIES: Respect the relationship.

RULE: If you found something you like at a gallery or show or through an independent art dealer, that is where you need to conduct your business.

WHY: When collectors circumvent the gallery–usually because they think they can get a deal by cutting out the middleman–what they are really doing is putting the artist’s business at risk.

Yes, this actually damages the artists career–the art community is small.”

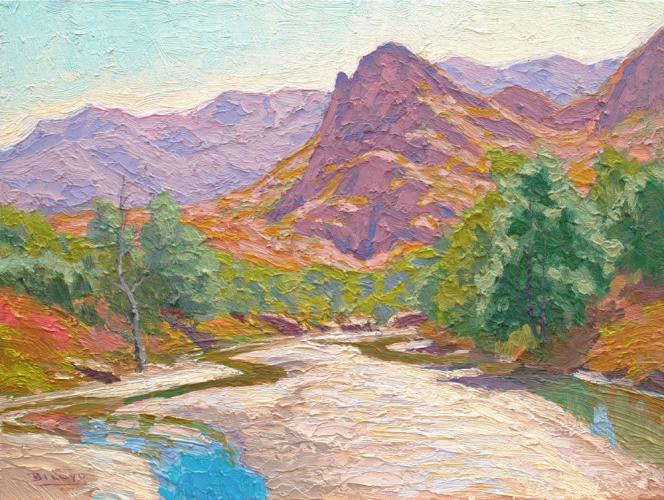

-Billyo O’Donnell (“Morning Light Over Leadville,” oil, 9×12 inches )

Faithless artists are usually dropped from the gallery as soon as this behavior is discovered. Losing this relationship can ultimately ruin an artist’s career because they lose the stability and benefits of having someone represent them and explain their work and pricing system.

“Over the last few years,” Billyo added, “there have been many artists leaving galleries and going out on their own to sell their artwork. I have learned that there is a direct relationship to having a long-standing association with a respected gallery and being able to maintain solid prices for your work.”

ETIQUETTE: Work with the dealer, be transparent, and ask lots of questions; it’s their job to educate you and help guide you through the process. And, if meeting the aritst is important to you and, in my opinion, should be part of your final decision, have the dealer facilitate.

Think of it this way, when you try to cut the gallery out of their rightful commission it’s like asking your doctor if you can avoid paying the hospital by going to his house and having him perform surgery there, at a discount.”

-Carm Fogt (“Altered Enso,” Chinese ink and mixed media, 24×24 inches)

EXHIBITIONS: If you saw the work of art at a show but the show’s over and the work didn’t sell, who gets the commission if you buy it?

RULE: People can argue this point, but in my mind, if you saw something you were interested in but didn’t buy at the show venue, it’s still considered–for a reasonable amount of time after the close of the show–proper to either run the sale through the exhibition or have the artist forward on the commission to the show.

WHY: Artists need shows and shows need reliable artists. It’s a great relationship when it’s working in harmony. Collectors help keep the harmony by understanding and supporting this important business relationship.

ETIQUETTE: Juried and invitational shows do have an actual end date, so, realistically, if it has been a month or so or if the work of art has since been sent to a gallery, the gallery would then take the commission, not the show. Often national exhibitions are established to support a cause; consider supporting the cause no matter when you finally decide to make the purchase of a work you found at the show.

Collectors need to be reminded of the expenses incurred when putting together an exhibition, whether by a non-profit for a cause or a private gallery.”

-Billyo O’Donnell (“Below Mount Lemon, Tucson, AZ,” 12×16 inches)

DISCOUNTS: when is it OK to ask for or expect a discount?

RULE: Discounts are for devoted clients who work with a dealer fairly exclusively and buy considerable amounts of art from that dealer or buy numerous works at one time.

WHY: In the days before discounting art became ubiquitous, dealers used this as a perk for their best collectors. Commonly, 10% was, and still is, the amount which would be split between the gallery and the artist, with each side absorbing 5%.

The biggest problem with discounts, if done frequently, is that they devalue the artist’s work across the board, meaning everyone who purchased work without a discount has, in essence, overpaid.

I remember a collector who commissioned me to do a painting,” recalled Dan Young, long time Coors Show artist. “It was back when I was starting out and really needed the money. I did the painting but then the guy asked for a discount. I wouldn’t do it. I walked away. Twice. Finally, he agreed to the price and bought it, but the whole thing left a bad taste in my mouth.”

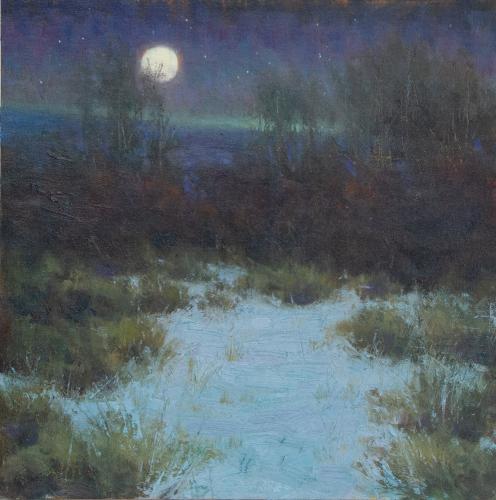

-Dan Young (“The Snow Moon Rises,” oil, 12×12 inches)

ETIQUETTE: Before asking for a discount, collectors should understand how prices are determined.

Often, painting prices are calculated by the square inch, e.g. a 16×20 is 320 sq in, at $10 per, the painting will be priced at $3,200. Pricing editioned work can be determined by edition size, how complicated the work is–how many plates for a hand-pulled print or how large for a bronze–and importance or relevance, especially with photography. THEN, pricing structure is predicated on artist’s longevity, the stability of their prices, and what the market will bear.

- How long has the artist been working professionally?

- How do they price their work?

- What national exhibitions have they been invited to and participated in?

- What kinds of publicity have they garnered–magazine editorials, awards, honors, inclusion in major collections?

I don’t raise my prices every year,” Dan said. “I may bump them 10%, if I do. Sometimes I only raise them 5%, depending on the market. Artist have to know their market and raise prices in a smart way; collectors want the value of their paintings to go up.”

-Dan Young (“Last Hurrah,” oil, 12×10 inches)

“People who truly connect and value my work,” Carm added, “rarely ask for a discount.”

COMMISSIONS: no art directing allowed.

RULE: The aritst is not an extension of you.

WHY: Commissioning an artist doesn’t give you free rein to dictate anything beyond the size, medium, and subject matter you are interested in acquiring. When starting the commission process, always keep in mind that the artist doesn’t live in your head and you do not do the work that he or she does for a living.

I’ve realized over the years,” said California landscape aritst Kim Lordier, “that trying to get inside someone’s head to understand what they are feeling is very difficult.

Now my process for a commission is to create that balance of sharing ideas then allowing for first right of refusal. If I’m presenting the collector with a piece that I am proud of, it will be worthy of one of my galleries. That has only happened once, that a collector didn’t want the commission. But, then they came back six months later wanting to buy the painting and it had already sold.”

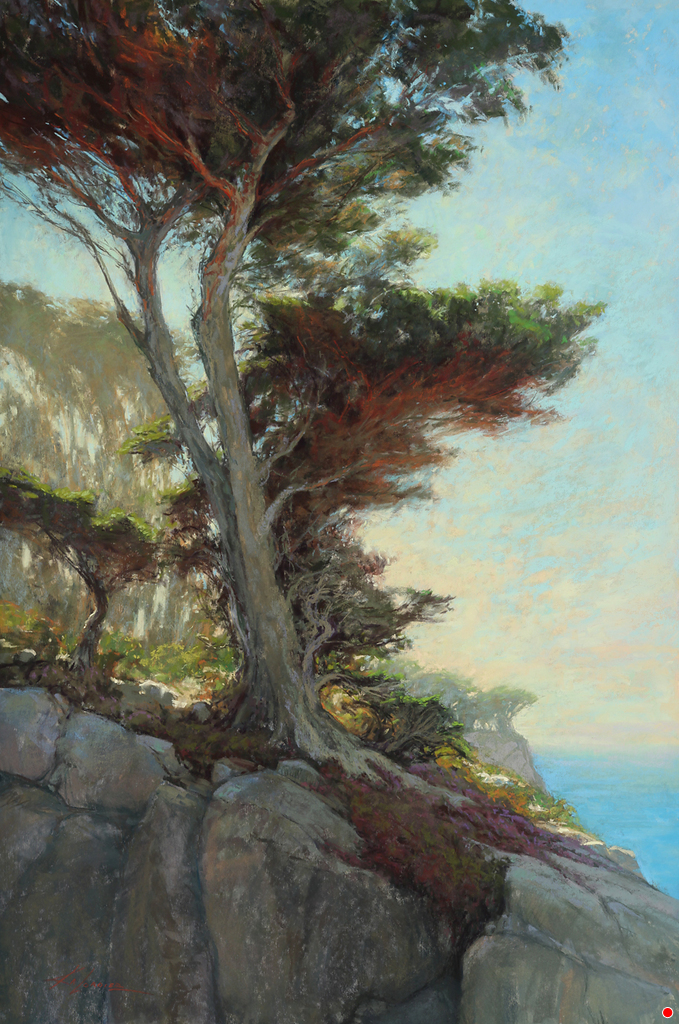

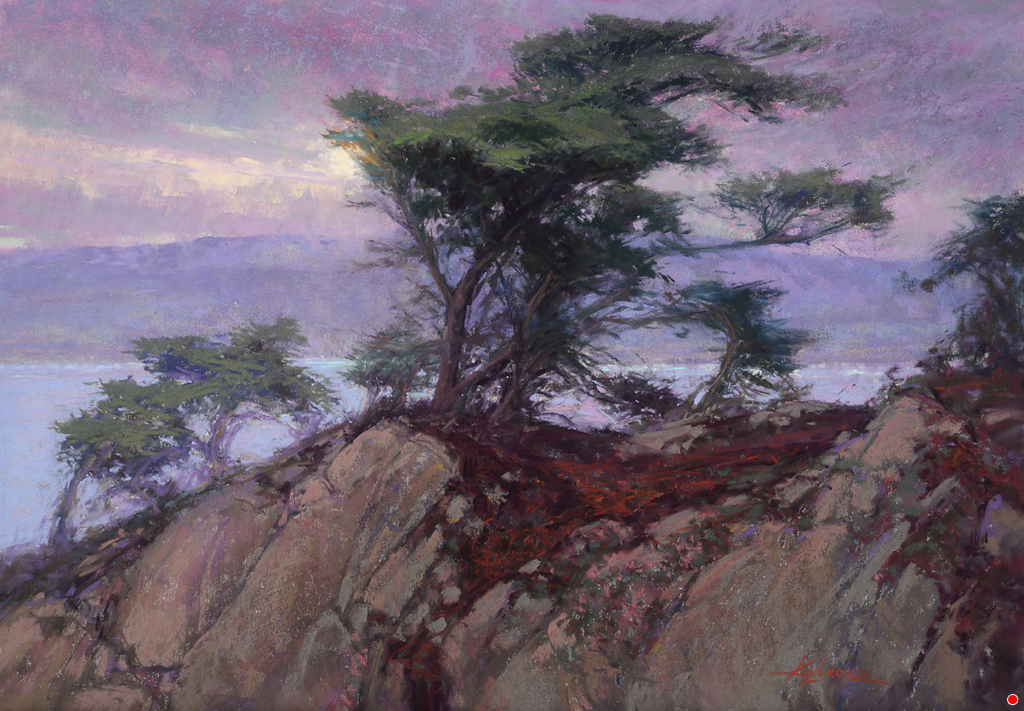

-Kim Lordier (“Intricately Interwove,” pastel, 36×24 inches)

ROSE’S DOS AND DON’TS FOR COMMISSIONING WORKS OF ART

- Let go of any preconceived concepts and allow the artist to create.

- Once you agree on a concept, price, and timeline for completion, sign a contract.

- You can ask for updates throughout the process but that’s it–no surprise studio visits, no emailing color suggestions or photos of your dog that you’d like the aritst to slip in.

- Many artists won’t take commissions, so don’t expect everyone to jump at the chance. (Nearly every artist I know has a horror story about a client who decided, mid-process, to dictate changes and treat the artist like a servant. The end result: either the client was fired or the finished work was rushed just to get rid of the client.)

- Consider using a dealer or consultant to manage the process; they can work through issues that arise and can keep the project on target.

- Expect to pay 50% down before the artist gets started. Enter this relationship knowing you won’t get this money back if you don’t like the finished work.

- Do NOT ask an artist to replicate a work of art that already exists, especially a work of art by a different artist! Original art, whether commissioned or not, is just that: original and unique.

My two-cents: If you’re really wanting a specific vision, consider taking art lessons. Who knows, maybe there’s an artist in you struggling to get out!

STUDIO VISITS: a time honored tradition.

RULE: Never show up unannounced. Always confirm your appointment. Do not assume you can buy anything out of the studio and that you can get the work you see at “wholesale.”

WHY: Studios are sacred spaces. They are personal and creative, but also professional places of business. So, plan for an amazing behind-the-scenes opportunity by researching the artist before you go. You’ll have a base of knowledge so you can jump right in.

I rarely invite collectors to my studio,” said Lordier. “Sometimes it feels like people are rummaging through my lingerie drawer. I feel judged, feel compelled to make excuses for why this or that is at a certain stage, even though that is not the visitor’s intent.”

-Kim Lordier (“Goodnight Sea, Goodnight Tree,” pastel, 12.5×18 inches)

ETIQUETTE: Keep judgements to yourself. Art in a studio will be in various stages of completion. The artist has a vision, whether he or she is struggling through a work, trying something new, or trying to make something work that, so far, has been fighting them all the way. Generally, artists will not have this work out for you to see, so don’t rummage around the studio.

Ask questions. Seriously, if you don’t know something, ask. If the artist uses a term or refers to some aspect of the work that you’ve never heard about, have them explain.

Tell the artist what you like and what interests you about the work. This is a great way to find out more about technique and what inspired it. Alternately, if there is a work you don’t care for, you could ask about it–without judgement–so you can learn why the artist believes it is successful.

Visiting artist studios is one of the best parts of my job as a curator; I always look at it as a privilege. If you’re invited to an artist’s studio, plan for at least an hour, do your homework, and don’t be afraid to ask questions–just keep it professional.

Still have questions? Send them my way. Chances are other collectors are wondering the same thing.