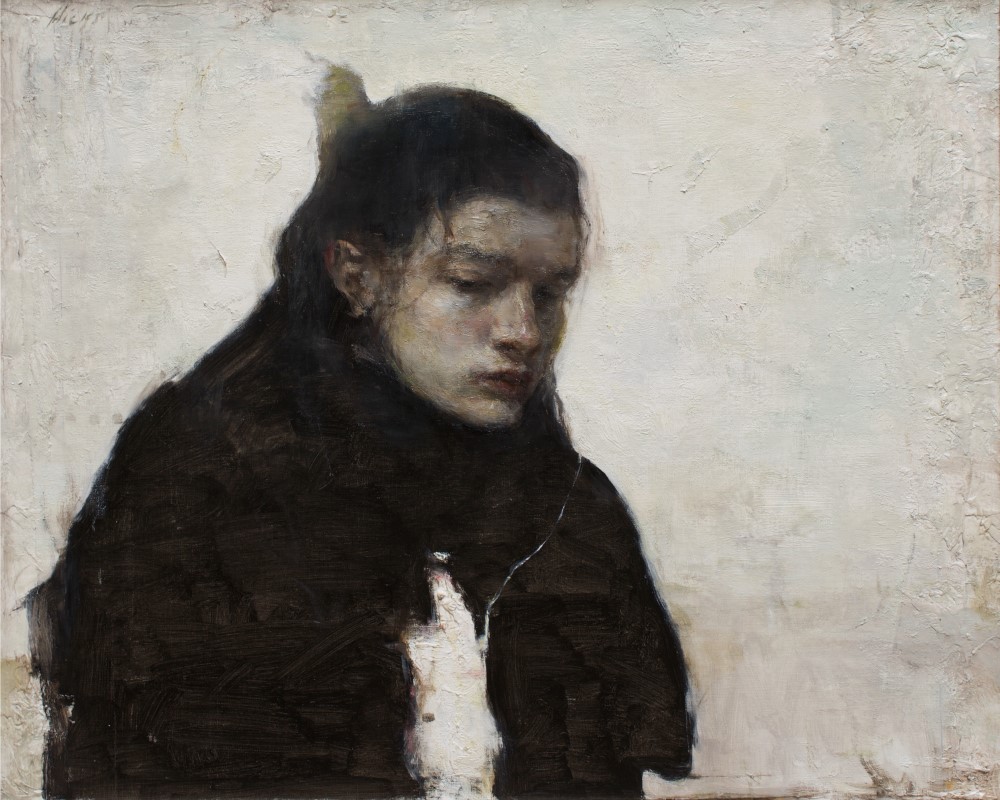

Where his work had explored themes of human connection through a direct approach to painting the figure, now clear ideas of what his subjects are thinking are obfuscated by abstraction in brushwork and color, and even with the application of torn canvas, recycled from past works destroyed in order to create spaces for these new works to emerge. The resulting paintings are far deeper, introspective and searching, and at the same time, outwardly involved in contemporary issues of our time, embracing perspectives that leave the viewer with more questions than answers.

Ron Hicks will be featured in a one-man show this August at the Western Center for the Arts in Grand Junction, Colorado. The paintings that make up the corpus of the exhibit—approximately 20 in all—though still figurative, now embrace perspectives and explored themes of human connection through abstraction and, at time, surrealist imagery. A man floats through a canvas perhaps to or away from a woman who reaches out to him; a portrait in profile with a priest’s collar give off a sense of calm; a woman peers out from behind thick abstracted shapes, hiding or trying to break free. In all these works the representational calls the viewer first but then as one is drawn in, aspect falls away in places but grow stronger in others, hinting at subtleties that were not apparent on first notice. Clear notions of what these figures are thinking are obfuscated by abstraction, just like in life—can we really know what someone is thinking, feeling, desiring?

When a curator from the Western Center for the Arts spotted several of these newer works at a show in Denver last year, her reaction was ecstatic and immediate: she invited him to show his work at the museum in a solo exhibition. With a short deadline—less than a year—Hicks, unlike most artists, agreed, knowing that the pressure of a deadline such as this would force him to clear his schedule and work. It also gave him the platform to create without thinking of the market and, as he put it, ‘let the chips fall where they may.’

I sat down for an interview with Hicks before his museum exhibit to see a handful of his latest works and find out where this journey has taken him.

Rose Fredrick: Let’s talk about the new work. How far back did the idea for this series of paintings start?

Ron Hicks: About four years ago. In its infancy, I started playing around with the idea of combining representational work with some of the abstract tendencies that I have and some non-objective passages and thought, there’s got to be some way to make this work together. About that time, I happened to come across the story of Adam and Eve. As my mind wandered while I read, I thought Eve got a bad wrap. I wondered what happened to her during the course of being cast out and I started to think how there was a connection with today’s events. And not just Eve.

Fredrick: But your paintings aren’t necessarily spiritual; they don’t follow the biblical story.

Hicks: I didn’t want to approach it in a way where I was, you know, there’s Adam, there’s Eve, there’s the apple. I wanted to take inspiration from the story and then give it its own life. And, I wanted to focus more on her because, again, I think she got the bad end of the deal. But if you think about having a place to stay then you’re not in that place anymore—it’s kind of like being a refugee. There’s all this talk about refugees coming to the country, what are we going to do with them? There’s this sense of abandonment. And there are families involved. If you can imagine, you’re in this new place—how do you make it? A lot of my thoughts on this show deal with love and empowerment but also a sense of vulnerability.

Fredrick: Let’s talk about inspiration for this series.

Hicks: The source for my inspiration comes from several places but the majority of it is just myself and the thoughts that are wandering around in my head. I’m a people person. I’m a painter of ideas. I like posing questions and I like the viewer to have their own take on it. I’m a participant but I’m not the end-all. This particular show with Eve, I started thinking, ‘My gosh, what would it be like to all of the sudden have nowhere to go or be in a new place and have to fend for yourself?’ And I thought, how could I represent that in some of my canvases? More importantly, this work has abstract and non-objective existence—how do you do that without having things that are more tangible? Like, props. How do I make that statement?

This body of work has been experimental and very interesting to tackle because, in a way, it’s more difficult than just painting something that is right in front of you. Going back to the apple, say I had an apple right in front of me. It’s tangible, I can look at the apple then represent it somewhere else. By comparison, that is much easier to do than to come up with something that has good design, harmonious relationships, has an emotive message intertwined—it’s a difficult thing to do.

Fredrick: You’ve told me that until recently you used to work a lot with models and you still bring models in.

Hicks: Yes.

Fredrick: But now these works are not necessarily based on a model. Would you talk about the evolution of working with a model and with some of your photo reference material from the past and where that departure happened for this new work?

Hicks: When I’d paint in the past, I’d bring a model into the studio and have a session that would last three to four hours. And I’d bring the model back for more sessions. In this case, when I bring a model back into the studio, it’s for informational purposes. And it’s based on my thoughts after I dig into the painting. I will start with some abstract passages and, because I painted so many figures in the past, I can lay down some basic idea for the figure then do a search for models for reference or even reference some photos of models I’ve taken over the years.

Fredrick: Most people know what I blank canvas looks like: smooth, wrapped on stretcher bars, and an artist goes from that point forward. What you’re doing is different though. Would you talk about the blank canvas you start with and how paintings evolve?

Hicks: In the process of this work, I start with a blank canvas like many artists do. But I have old canvases in my studio, like pieces that you might cut off. I started collecting these pieces of canvas before I knew what I was going to do with them. But I thought, someday these will come in handy. For this new work, I used some archival glue, and, on a support, I started laying down these pieces and ripping them and tearing them and laying them down abstractly on canvas and then, in turn, taking what I have before me and using them as inspiration to move forward. It sort of has a ‘found object’ feel to it, almost a sculptural setup to begin with. In other cases, the texture is created by applying layers and layers of paint. I start most of my work with abstract scribbles and I sort of wait for inspiration.

Fredrick: What do you mean, you wait for inspiration?

Hicks: Sometimes these canvases will sit around for days, even weeks while I move on to something else. I’ll have probably two to three different canvases going at the same time; that keeps me fresh. So, instead of letting one sit, if I’m inspired I might go right in and start developing it either abstractly or maybe even start with something more representational and combine the two at the same time.

I’m really into this texture thing right now; that’s where the fun comes in, building layers of texture over other textures. I love seeing the history of the painting. You can see all the way from the ground level to the tops of buildings, so to speak. You see the layers—some transparent, others opaque—combining with each other.

Fredrick: Are you letting abstraction be more of a guide?

Hicks: Absolutely. I’ve always had this way of seeing things very abstractly and adding more and more—in the case of my earlier work—adding things that are more tangible, things you can sink your teeth into. Now, when I’m working with these abstract moments, I leave them and use them as inspiration. In my opinion, there’s not a lot of difference between realism and abstraction, and even the non-objective world. We’re all using pieces of pigment to create big shapes, harmonious dialogue. I have to find a way to harmoniously make it work together; that’s the search.

Fredrick: It feels to me that there’s another level to these paintings. I think that you’re probably a romantic person, you’re attracted to the figure and gestures but now there’s something deeper going on with these paintings, maybe a little more of an edge. Would you talk about the next layer you’ve added psychologically?

Hicks: The mind of Ron. (Laughs) These paintings are hard to describe for me. I think the difference in what I’m doing right now is that I’m opening myself up. Truthfully, I don’t know what that is. I’m trying to express whatever it is I’m feeling. It’s pure raw emotion that’s going into the canvas. To single out one thing is hard for me to do.

Fredrick: It feels like there’s more of a mystery to them. You mentioned refugees, families and homelessness, being a foreigner in a strange land—it almost feels like these paintings are foreign to you and you’re letting that happen.

Hicks: Absolutely. I think when I first embarked on this series, I had no clue what it was going to be. As a matter of fact, I only released a few pieces on Instagram. These paintings, I am really letting them be the path, which is very different from some of my earlier work. I’m responding to what is set before me. It’s pure emotion. Whatever comes out I allow it to be. And I’m not afraid to leave an area unfinished. My goal is not to dictate what these paintings mean. I have my own thoughts but what I really want is for someone to walk up to the canvas and go, “This is what I think is going on,” or “This is what I feel.” As opposed to “Oh, this is the scenario and it’s all laid out for me.” I think, being able to work in abstract or non-objective ways with some more realistic passages allows me to have a different dialogue.

Fredrick: There’s been such an evolution to your work.

Hicks: Early in my career, way back, I thought, if you could paint anything exactly the way it looked, that was great art. After I started to master transferring information to the canvas, I thought, well, that’s great but what am I going to do with it? Then I started having these paintings that were really about shape and value, but value in that I wondered how far I could push it, how close could I keep the values together and still maintain a harmonious dialogue. For many years I explored that side of it. People were actually concerned about me. (laughs) Kind of like…are you OK? If you need to talk, we can talk…

I’ve always had these moments of experimenting. The work isn’t solely about painting for the sake of it; there’s always an agenda. Throughout the years, I’ve moved forward. I’m at the other end of it now, so instead of the values being very close, I’m spreading out. Where is this going to take me? That’s an unknown. I think most artist go through this, whether they follow up on it or not, because there’s a lot of pressure out there to produce for galleries and have certain things that people like. But what’s tough is to say, regardless if whether this thing is marketable, I’m going to do what I have to do. Hopefully, it will be something that people can relate to.

Fredrick: Let’s talk about individual pieces. With the self-portrait, is it more a portrait of your inner self?

Hicks: Well, in this work, you can see inside my head. The whole Adam and Eve story—I was reading the bible. I have a strong Christen upbringing as a child. This piece that appears to be a preacher with a collar, it’s called “Sage.” There’s my face in there. I’m not sure why that came about but it went in that direction and I let it go there. People might look at that painting and think, what is he trying to say about himself. I’m not trying to say that I’m holy or some sort of teacher—it has nothing to do with that—but you start to reflect on your life. These paintings are a reflection of my life. I’ve started to think of mortality: What am I doing with this time I have left on earth? That painting echoes the time I’ve been here and what I can share based on what I have. I’m sure, as I continue to paint, there will be more moments like that. I would say, with this body of work, there’s a lot to do with me—everything to do with me.

Fredrick: The large painting called “The Yearning,” you have it hanging so that the man is floating in space above the woman—I love it this way—but it looks like it could also hang the other way.

Hicks: When I started the piece, in my sketchbook, I had it laid-out as it is. When it’s set vertically, it has a hopeful thing going on, like a man proposing. I chose the original orientation—on its side—because I didn’t want that to be the first thing someone saw—a man proposing. I’m trying not to give too much of this away, because I like people to see what they want to see. One woman saw this painting the other day and saw, in the swirls of paint, butterflies. I like that interaction. In the swirls of paint on some of the women, it reminds me of fertility. Anyway, I let my first reaction stand and kept the painting on its side like it was in my sketchbook.

Fredrick: Tell me about the painting of the woman with her hands over her face. It feels like the abstraction is closing in on her.

Hicks: That particular piece, [TITLE], that was about insecurities. I see her as maybe coming out of those insecurities but not ready to come out of that box. As humans, we have our front face then there’s our inner-side. We’re afraid to let that out because, in society, if you are too open people can take it as weakness. This painting is about how we keep things to ourselves and hold things inside. The jagged edge is like the harshness of the world.

Fredrick: OK, I’m just going to ask it. You don’t paint a lot of African American figures. In a way, your art is beyond skin color. But you get asked that?

Hicks: Oh, a lot.

Fredrick: Let’s talk about it.

Hicks: I consider myself an artist first. I paint what I see, what I’m exposed to. And I do paint a lot of African American subjects, but they don’t see the light of day for whatever reason. Some of it is marketing, some of it is that they are scooped up by clients before they hit the market. There are several African American paintings in the show but early in my career, ratio-wise, I painted more African American people but the longer I’ve been around, the tables have turned. In art school, at the Art Students League and in Colorado, there’s not a lot of African American models.

Honestly, I hate to go there but, if I’m honest about it, I’ve had people ask why I’m painting white people. It was kind of upsetting to them. I even had this guy want to purchase some paintings then he found out I was African American, and he wanted a discount then he wasn’t sure, then he just walked away. It’s kind of crazy.

Fredrick: You’re stereotyped both ways for not painting African Americans or for painting them—you can’t win. I wonder, with this new direction—it’s not really new, but another step forward—as much as it’s building up layers, it’s breaking down layers. I wonder it we’ll see in the future as these things kind of grow out of you, paintings like the “Sage.”

Hicks: There will be several of them in this show, so we’ll see what happens. And I don’t care. I want to express whatever it is however it comes out. 10 or 15 years ago, some of the galleries, they’d call and say, Hey, you really hit a homerun with this piece, you should do more of that. So, what happens is, you start painting for the market as opposed to painting for yourself. These days, I live for the moment of whatever I’m experiencing, and that’s what I paint. I wouldn’t necessarily go out thinking, I need to paint more black people. I’m not that kind of person, it’s just not how I operate.

Fredrick: You’re in a really strange position when you’re painting the figure: If you were painting landscape, no one would say, “Why isn’t that a black landscape?”

Hicks: Exactly. And from the other side, I don’t truthfully believe there’s “black art” either. When people say, why doesn’t he do “black art”? My response has always been: What is “black art”? I know that “back art” in the 60s and 70s there was a “black art” movement. I’ve gotten into some extreme debates with people about it. I’ve showed people images of black people portrayed in painting and asked if that was “black art” and they said yes. But all those paintings were done by white people. So, what is “black art”? Here’s some food for thought: if you go to the upper echelon of artists making a ton of money, if you look at black artist, they are talking about social issues related to the black male surviving in the hood. But if they were painting an African American with a suit and tie, you won’t necessarily see that.

Fredrick: There’s a black curator who has written negative things about Dean Mitchell, that he paints for white people. He told me he just couldn’t win.

Hicks: I’ve had the same kind of interaction. You’re not good enough for either side. If you go too far on either side, you’re selling out.

Fredrick: It seems, with this body of work, it’s got to be nice to forget about the market. And even nicer that the market has come to you in this work, has accepted it and is buying.

Hicks: Yes, that’s where I feel fortunate. Let’s face it, as artists, art is one of those things you don’t have to have. I feel very fortunate there are people who see fit to buy these pieces of paint on chunks of canvas, for that I’m truly grateful. I can’t imagine doing anything else, especially now. Early in my career, when I was balancing a job and painting, I thought maybe I’ll have to do something else. But now, after all these years, I can’t image doing anything else.