In other words, you will not be passive in front of these paintings; meanings are a reflection of you. Is life a self portrait with the constant reminder of your impermanence hanging over your shoulder? Are you confident enough to stand alone in front the crowd yet remain composed? Is it the thinnest strand of spider’s silk that holds your days together, one after the other? Ultimately, what is left behind when you are gone?

This exhibition is an ethereal look into the mind of the artist. Running his hands across many facets and intrigues of life, Sprick uses his well-honed craft to explore the psychological baggage of mortality. This work is not meant to leave you uneasy. Instead of conflict, he offers questions beautifully couched in sparse settings that allow plenty of room for reflection.

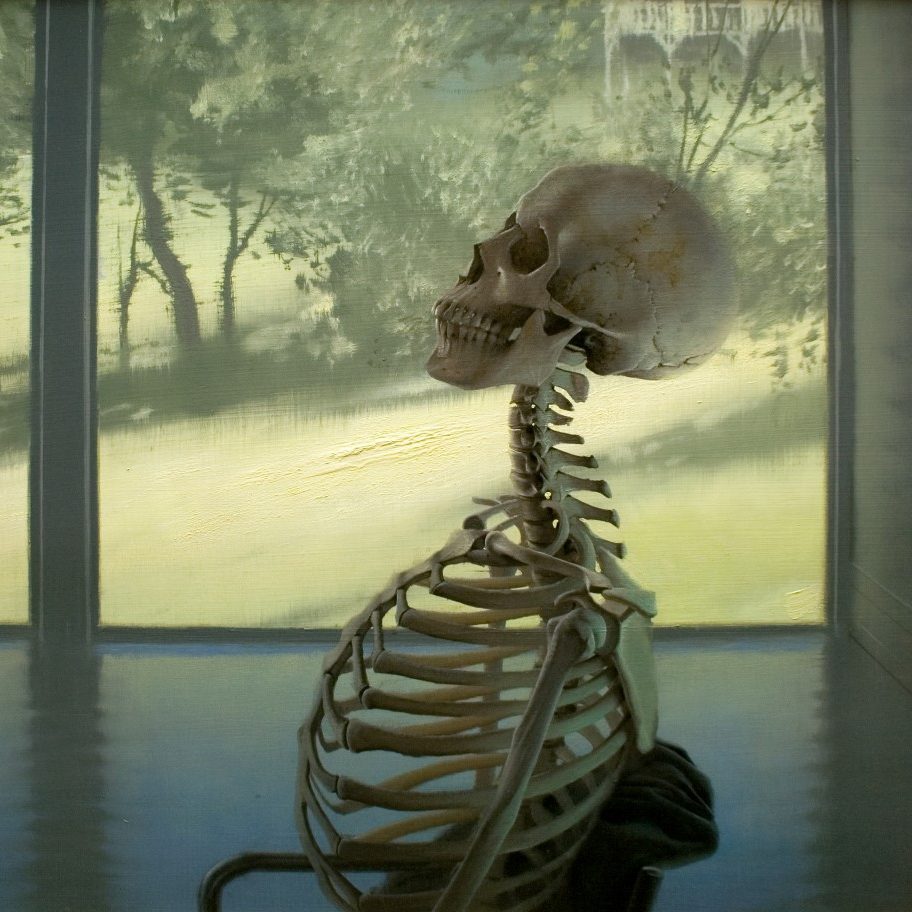

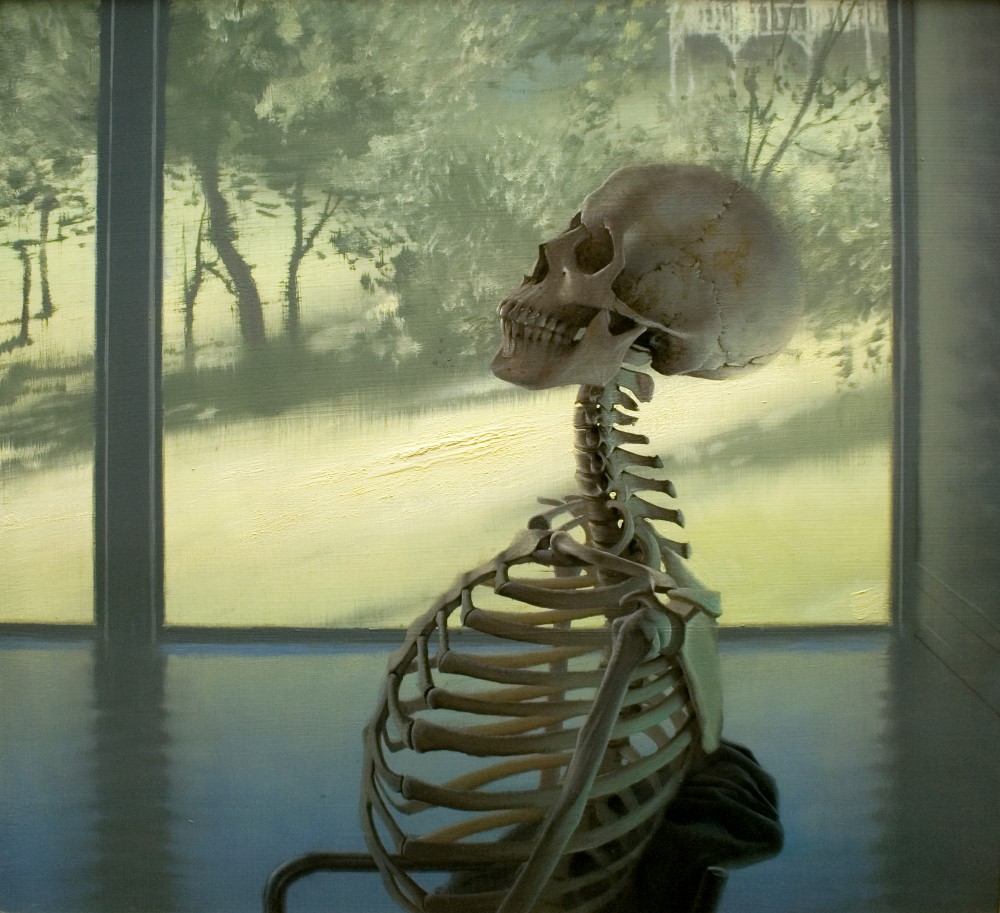

To that end, he has simplified his compositions leaving out details that in the past he might have felt compelled to describe further. He has chosen to delve more deeply into the shadows finding delicate nuances within. And, unlike most historic representational painters, Sprick avoids dramatic light affects in favor of back- and muted-lighting. He further cuts down on vivid color reflecting off his subjects by adding a secondary blue light source, which illuminates the shadows as they fall off into darkness. In this way, the simple, graphic shapes do not compete with his ultimate task: to portray the immense world confined within the walls of his studio.

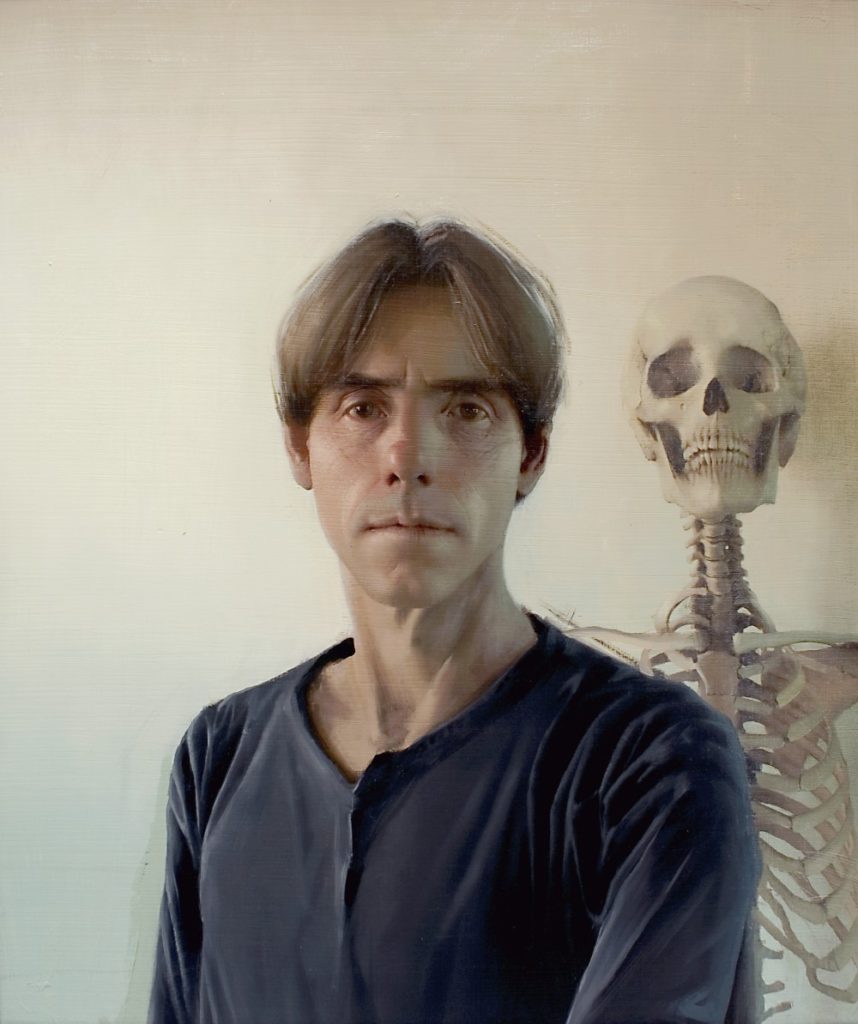

These objects he paints — from skull and skeletons, to the human form and ripening fruit — at the hand of another would be, perhaps, mere props, or simply superfluous. It is Sprick’s desire to be real while feeding intention into these things that turns the common into mythic. This is so elegantly seen in the figurative paintings in this show. Not bored, romanticized or uptight, his subjects look out at the viewer, appearing grounded and self-assured. All in all, these paintings of both the living and the dead are not sentimental but unvarnished, deeply human portraits.

Part Two

Conversation between Daniel Sprick and Rose Fredrick, August 20, 2008

R: Has there been an evolution for you in this latest body of work?

D: It’s really not a conscious choice or shift. I keep painting whatever is next or what I’m drawn to. I do like to paint things in a series, so if I’m drawn to a particular subject than it generally suggests another one.

R: The skeletons have always figured in your work. Why?

D: I can kind of attribute that to a few things. When I grew up my father made false teeth and had articulated dentures all over the place. One of the ways he studied dental occlusion – the way the teeth go together – he had an authentic human skull that he bought from a biological supply company. It was around since I was a little kid and I was always used to looking at it.

The human skeleton is quite irresistible to me. I can’t help but see my own life there, and it’s a compelling and beautiful subject, outwardly beautiful and sculpturally. And it has a haunting presence that can’t really be ignored. Though I don’t see it really as much as other people do because I’ve had these skeletons and the skull in my studio for so many years that I’ve stopped seeing the symbolic components and see them mostly just for their visual properties.

R: Of these paintings, are there certain ones that stand out for you?

D: I guess that probably the most challenging of the paintings is Skeleton Table. I kind of knew that it might be difficult for some people because it’s confronting about mortality in a way that people get uncomfortable with.

R: The skeleton seems to be in the same pose as the reclining nude [title]. Was that intentional?

D: No, actually the skeleton was done first than the nude came later. For me it’s kind of a fortuitous coincidence because I wasn’t thinking closely along those lines. It’s hard for me to retrace my steps when I painted the Skeleton Table, but I do remember that I had a lot of preliminary drawings for it before I started and some drawings that I had been accumulating for almost a year that kind of led to this. I was thinking of an obscure Japanese composition – I don’t remember the piece – but it was a kind of a still life subject placed at that height. That painting morphed in my mind to the subject of the sky burial, which is a type of disposal of human remains by putting them up on high so that scavenging birds would pick and take away the remains. Although, that occurs outdoors where the birds can get to it, not indoors, but somehow that elevation made me think of a sky burial. I found the whole notion of it quite poignant.

R: Are you purposefully going for symbolic meaning in paintings like Skeleton Table?

D: I don’t really dig that deep for symbolic meaning. The uninteresting fact of the way I work is that I mostly paint things because I just like the way they look, simple esthetic enjoyment. I know some of the subjects are loaded but I mostly leave that up to viewers. Some of the subjects seem ponderous but I’m not really a morose, death-obsessed character.

R: That’s good to know.

D: Yeah. I mean no more than anybody else is. I’m living full-force and having a goodtime living fully, so it’s a little mysterious why these subjects keep reappearing.

R: Speaking of which, I read that you added a skeleton to one of your self portraits long after you finished the painting.

D: Yes, probably a couple years after. It was sitting in progress in my studio for two or three years, and I could never figure out exactly how to complete the painting. Then I got the idea to add that skeletal figure. I thought it was actually just the right solution to it. I was really pleased with it. Meanwhile, I just got that painting back. It’s here in my studio because I’m going to trim some parts of it off. The main compositional elements will remain, I just don’t think it’s using all that space, so I’m cutting off the top and bottom so it will now be a horizontal. I bet it’s now four years after I started that painting. In a way, a piece is never really completed.

R: Ever?

D: The hard thing about being an artist is that you’re all full of after-thoughts about what you could have done with a particular piece. It will never really be done until your dead. Then they are done. It’s never done in the sense of being satisfied with it.

R: With models, do you pick the pose or do they?

D: What I find is that I may have a clear idea in mind before the model even arrives but it could be that something else will come up that’s even better. I try not to be too locked into preconceived notions, but I still do. I still make that mistake but I wish I didn’t. This whole business is a life long learning process.

R: How long do models have to sit for you?

D: With the models, these days I’m able to take advantage of digital imaging because I’m not able to have them for 40 or 50 hours. It’s just maddening. When I’ve done that before the work goes on for months and months and sometimes I never finish. For any number of reasons, the model doesn’t show up anymore and you just can’t finish your painting. So, I’ve learned to take advantage of an excellent tool. It helps me with transitory subjects, which models are. I think that’s kind of the reason a lot of artists do self-portraits: it’s more the model than any great interest in documenting one’s self. The model will definitely stay around.

R: Let’s talk about your art, your craft, and how it’s a vehicle to reveal some deeper aspect of yourself.

D: I think actually that your true self comes out whether you want it to or not. I didn’t always think that but years later I’ve come to realize it. It’s true that art can be calculated, calculated to please critics or to be salable or done for some ulterior motive; but I think if an artist has an ulterior motive – say to make it as weird as possible, or so it will be talked about or if it’s just the most innocuous subject so he can sell it more easily – whatever it is, that is the artist’s true self regardless of what is expressed. I hope that in the case of my work what comes out it something useful and interesting.

R: What do you mean by useful?

D: Satisfying in an aesthetic sense, satisfying rather than frustrating. A lot of art work is intentionally frustrating, and I think it’s a mistake.

R: Do you block out the audience when you are painting?

D: I don’t know. When I was younger I used to think adamantly yes, but if that were really true then you wouldn’t even show your art work. Clearly, you’re dong work with the intention of somebody seeing it; for whatever reaction you are hoping for. Human beings don’t work in a vacuum. An artist who says he disregards completely what anyone thinks isn’t telling the truth. On the other hand you shouldn’t cater to tastes.

R: So what is your true self?

D: It’s what’s revealed in the work, what you see. I can’t really articulate it but it’s everything that I experience, my mental state, my desire for perfection to the extent that I can reach it, it is pride in craftsmanship. It’s basically a display of my taste, good or bad. It doesn’t mean anybody is going to concur or has to.