Over the course of curating and installing the 2022 Coors Western Art Exhibit & Sale, I noticed something quite remarkable. The entire show from paintings to sculpture, photographs, and prints, has an overwhelming sense of calm.

But why? Truly, of my 26 years curating this show, why is this year so much different than any other?

I mean, it’s not like the world has gotten safer and we’ve beat the pandemic, cured cancer, and handed out cute puppies to all. Certainly, artists have suffered through this weird, stressful series of dramatic cultural changes just like everyone else.

If anything, the pandemic hit the art market especially hard–and we’re already one of the most fickle and flat-out unstable places to work as it is. Galleries and museums closed their doors overnight, shows were postponed indefinitely, and workshops canceled, which meant artists were suddenly stranded, cut-off from patrons and collectors.

And yet, the work that these artists in the Coors Show produced over the last year–the work I had just watched my installers hang–is inspired, hopeful, and stunningly harmonious.

I have a theory

Whether you like change or prefer the status quo, I think it’s fair to say that the changes thrust upon us all thanks to COVID have stretched the limits of even the most amenable among us.

I suspect, however, that for artists, once the initial sense of terror settled down, a long, slow sigh of relief rose to the surface.

Suddenly, artists everywhere were summarily relieved of deadlines. One day it’s the grind of constant nagging stress, the next, there’s room to step back, to think, to play.

Don’t get me wrong. Every artist I talked to has struggled with COVID and isolation. Despite the common depiction of the artist as loner, most artists will tell you that they heavily rely on gatherings of their peers to paint and draw together, and critique each others’ work over bottles of wine. In other words, inspiration is often found in social interaction; art is very much a team sport.

And, so, standing amid so many truly authentic and subtle works of art, I had to wonder:

Are artists uniquely capable of adapting to change more so than others?

The Psychology of Change

Times of upheaval–great depression, wars, a pandemic–create interesting opportunities to observe evolution. Humans are in the petrie dish, so to speak. The question of the hour is: how quickly can we change and adapt?

Or not.

For some, this disruption in the status quo has been cause for panic, even anger, and the need to dig one’s heels in while pushing back with great force.

But why is change so hard for some while others, albeit not thrilled, seem to roll with it?

According to a 2012 article in the SAGE Journal titled “An Analysis of Resistance to Change Exposed in Individuals’ Thoughts and Behaviors,” by Lena M. Forsell and Jan A. Astrom, “all psychological resistance is built on a fear of change where the outcome could result in a worse situation.”

Everyone experiences resistance to change to some degree, but most of us think things through and deal with it. However, research shows that the ensuing fear of change can often be traced back to “the attitudes and behaviors of the [person’s] parents or other adults from their childhood.”

Yep, that’s right. Go ahead and blame your parents for this one.

That’s science, my friends.

Hoping to Sprout Wings

Though I’m in the camp of folks who get peevish with the status quo, I’m not the most confident of women, by a long shot. I do admire it in others, probably because I recognize that it doesn’t come easily for me. I bring this up because I don’t think an abundance of confidence is the key ingredient to an artist’s ability to adapt to major societal changes, such as a pandemic, and not just because I don’t have it.

It’s a strange kind of push-pull, in my mind, to love change, even the change that feels like you’re walking off a cliff, hoping to sprout wings, and yet struggle to ask for help along the way. Asking for help always feels like admitting failure. That I’m a fraud, an imposter. I’ve written about the imposter syndrome and the fear of failure in my blog post, On Voice, because a lot of us in the art world suffer from an overactive inner critic.

Either way–too much or too little confidence–my guess is that we can toss confidence out the window as a factor in my theory as to why artists seem to have weathered the pandemic better than others.

A Little Fear Goes A Long Way

Art is, by its very nature, abstract and ephemeral. Not all minds can hang in that space for long. But for esoteric, searching thinkers, this is home. Change in this space is ever present and, if not always readily embraced, it is, generally, quietly accepted.

Accidents lead to innovations that are frequently lauded among peers. That giddy feeling of being on to something profound–or stepping off the precipice into the abyss–can be an incredibly exhilarating space.

If the nearly 400 harmonious works of art in the 2022 Coors Show are evidence of anything at all, I think it’s that art thrives when the mind is free of deadlines and the demands of the market–something that happened overnight when COVID struck.

There was also no time for self-doubt; artists had to keep making art because it’s what they do and who they are.

An artist must trust that art makes the world better because it gives meaning to, well, everything. As unstable as a life in the arts may be, it very well may be the safest place for the wild minds that strive and survive in spite of societal upheaval.

Embrace Change Like an Artist: PART TWO

I recently curated one of the most impactful shows I’ve ever worked on. Mental Health Through the Eyes of Artists ran this fall at the PACE Center, Parker, Colorado.

While COVID has been a global trauma, the artists in this show struggle with internal trauma, physical pain and disabilities that left many contemplating ending it all.

Art became the eye of the storm.

This show came about thanks to Idaho artist Scott Switzer whose recent body of work tells the story of a friend’s schizophrenic son who was killed by a police officer. Ethan, 24 at the time, was shot in the back while running from a homeless camp. He had committed no crime, was shirtless and shoeless, and had no drugs in his body. He was in the midsts of a psychotic break.

Ethan’s death hit home for Scott, who also has a son with schizophrenia. And Scott, he deals with his own mental health issues.

Just as asking for and accepting help has been difficult for me, this show brought to light just how difficult it is for some people to talk about mental health. Yeah, I’m including myself here.

But why?

Isn’t this reluctance part of the reason we have so many people struggling and isolating themselves when they need help the most? Hell, isn’t this why I’ve stayed stuck in bad situations, growing more and more angry with myself for my inability to get unstuck?

Scott’s work and willingness to speak openly about his son and his own challenges sent me down an incredible path. I knew this was an important topic and that art was the perfect vehicle with which to start the conversation.

And, because I wanted to include Colorado artists, I reached out to the Denver Veterans Association. Wow. I had no idea that I would get to know so many truly brilliant artists whose work brings to light such honest, open, and vulnerable emotion.

Many of these artists are dealing with PTSD, depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, and constant physical pain.

More than one artist told me he had held a .45 to his head, thinking of ending it all. Their stories of finding community through the Veteran’s Arts Council and how creating art allowed them to face some truly astounding challenges gave me unforgettable and precious insight into the resilience of the human spirit, and the unique ability for the act of creating art to heal.

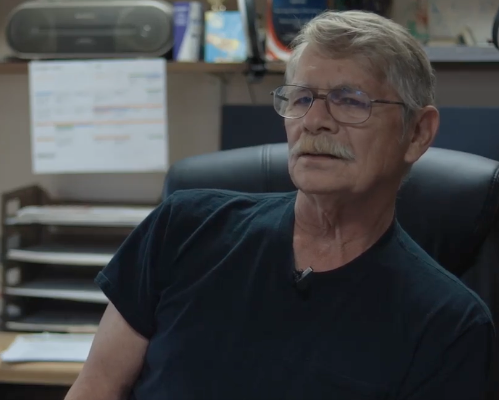

A Man with a Vision is Never Truly Blind

Jim Stevens was one of those veterans who thought of ending it all. A Long Range Patrol Leader in the Army during the Vietnam war, Jim was shot in the head while on a combat mission. Though he recovered, the bullet left fragments in his brain that gave him severe migraines, which he still endures to this day.

When he returned home, he took a job as a professor at the University of Colorado and resumed his art practice, something he had done his entire life, starting as a kid when his grandmother taught him to paint.

In 1993, that all changed when a migraine caused a bullet fragment to move and trigger a stroke that, in 30 minutes time, took his eyesight.

“I found myself divorced and the blind single parent of two preteen daughters,” Jim told me. “I lost my job and all confidence in my art.”

At that point, Jim sank into anger and depression.

“I was so angry that I destroyed my motorcycle with a crowbar and trashed my unfinished art pieces with a baseball bat and ripped up most of my notes, drafts, and records,” he said. “It took many years to accept being blind.”

Through it all, his daughters kept asking him to make art. Finally, in 2000, Jim went back into the studio.

Heading the Call for Help

Legally blind, Jim sees the world through pin-pricks of vision. He told me that, when in front of me, he could see one of my eyes but to see my nose, he had to move his eyes to focus on that. Everything else was an empty void.

Obviously, his initial attempts back trying to make art were slow and frustrating. His initial attempts were rough, but he soon discovered that the more he created, the more he felt he could accomplish. “I kept working and relearning the craft, learning how to do my art without the eyesight an artist so desperately needs.”

With patience, he was able to remastered the skills he’d learned before the war and his injury.

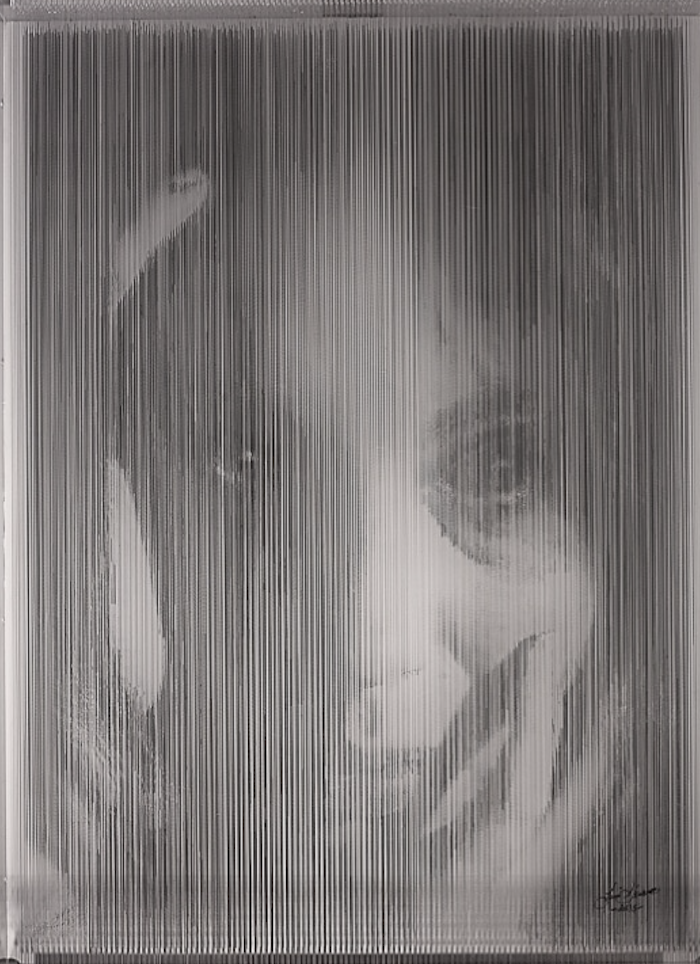

Then this happened. From the backyard, one warm summer afternoon, he heard the pained cry for help from his six-year-old grandson. While practicing his casting, the line from the boy’s toy fishing pole had gotten stuck in a birds nest. As Jim stood in the backyard, hands full of tangled fishing line, he thought, “Yeah, right, the old blind guy’s gonna fix this.” But then a cloud moved over head and blocked the sun. Through his pin-pricks of vision, it created the illusion that the monofilament line was rippling in his hands.

“I couldn’t get that image out of head,” he recalled. “I kept thinking, how could I create something out of this material?”

Soon Jim began experimenting with monofilament, trying to recreate that sensation, but how? After much experimentation, he realized he had to lay out the fishing line on a grid. From there he started painting on the individual stands of monofilament which he then stacked in separate layers, one on top the other. Together the disparate layers filled in the missing notes and created a complete image.

With the aid of special lenses, Jim has been able to create art that not only communicates his inner vision but also, in a way, allows people to get a glimpse of the world through his eyes.

“I paint each layer with a slightly different shade, so that paint pulls your eye through,” he explained. “It takes about two month to paint one work of art because each layer has a complete painting on the monofilament.”

Jim has, in this work, brought us into his mind’s eye, which is decidedly not blind. “With these monofilament paintings, I’m literally painting one strand at a time, straight ahead. The abstract linear paintings, those portraits are hundreds of individual lines.”

Between the lines, there is nothing. Just like his vision, it is empty. “The way I paint reflects the way I see the world. I can see your eye. I can see that one strand. But for me there’s nothing on either side. I have to move my eyes to see where that is. When I look at one spot, it’s just empty.”

Jim’s work continues to evolve despite his physical challenges. His latest portraits are painted on a clear acrylic panel that he floats over an abstract painting on komatex panel. “The portrait is painted without shading,” he said. “The abstract painting creates all the shading in the portrait.”

What's Your Motto?

I could stop there, with Jim’s art and his incredible spirit, but I’m sure you already guessed that Jim has impacted lives beyond art. In 2015, he and his fellow creative veterans banded together to create the Veteran’s Arts Council (VAC) at VFW Post 1, in Denver. The program gives veterans a place to gather and create art and show their work. Jim insists on bringing vets into the mainstream with the Arts Council, as well, by holding first Friday openings and finding new venues to showcase the art of his fellow soldiers. The VAC even pulls in non-veteran artists to participate as well. And, naturally, Jim has been asked to help start VAC programs across the country.

For the opening of the PACE Center exhibit, we had a panel discussion, Bringing Light and Love to Mental Health. Scott Switzer and Jim Stevens were among the panelists who spoke openly and frankly about mental health and healing through art. Many artists from the show were in the audience and contributed to the conversation that emphasized the importance of talking about mental health as a way to lessen the stigma surrounding the topic.

One of my favorite moments in the conversation was when Jim explained his approach to working with veterans who are struggling to see a good way around their problems.

“I tell them to focus on one line for life,” he explained. By this he means, find your motto, keep it simple, reflect on it daily to stay focused. Don’t try to solve all your problems in a day; that simply won’t happen.

Upon hearing this, Scott said, “I think my motto is: I know there’s a god and it ain’t me.”

Amen to that.

Here’s Jim’s motto and mine.

“A man with a vision is never truly blind.” -Jim Stevens

“Ask for help; there is grace in vulnerability.” -Rose Fredrick

6 thoughts on “Embrace Change Like An Artist”