In the age of “fake news” and “alternative facts,” more and more, I find myself contemplating the notion, who gets to tell the story. Because, whether we’re talking literature, painting, sculpture, photography, or any other form of art, the artist is telling a story; he or she is recording that moment in time and communicating a version of events. And I don’t mean documenting. I mean, the finished work shares some inner truth of the artist’s life, if it’s truly art.

I recently ran across The New Yorker staff writer, Louis Menand‘s 2018 article, “Literary Hoaxes and the Ethics of Authorship,” and was struck by how much of what he was discussing had parallels in the art world. In particular, his suggestion that there is an “autobiographical pact” between writer and reader. He explained:

“This is the tacit understanding that the person whose name is on the cover is identical to the narrator, the “I,” of the text. [I]f the name on the cover seriously misleads us about the identity of the author, we can feel we have been taken in.”

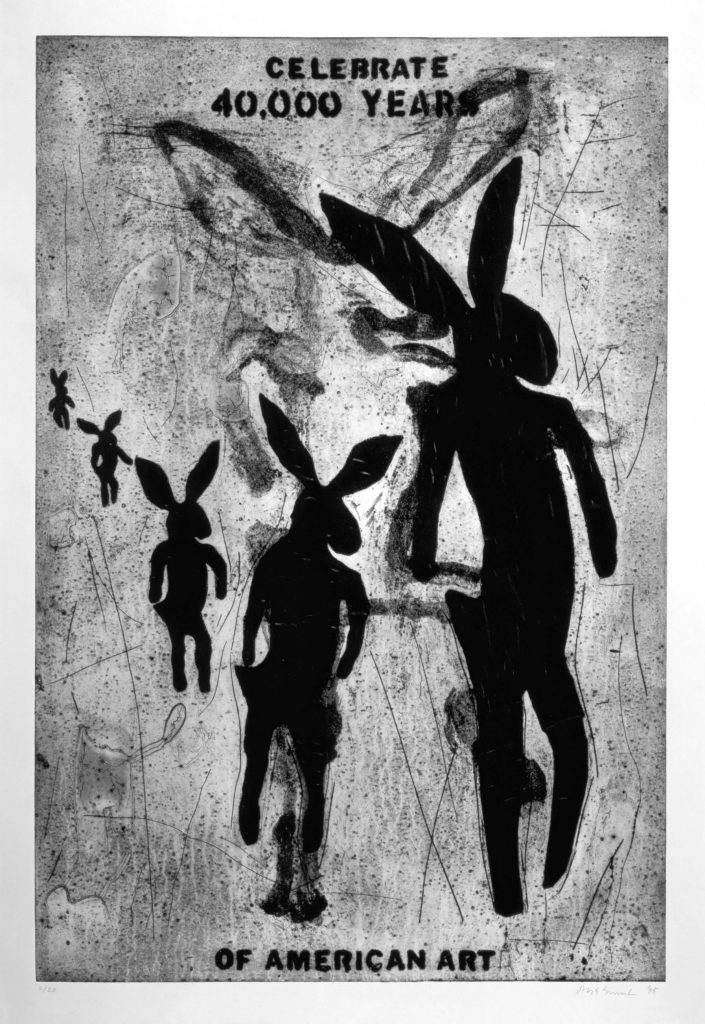

Interestingly, Menand went on to say that “the distinction between fact and fiction, although it may appear fundamental, is a fairly recent development in the history of writing, only two or three centuries old. Along with that distinction came the practice of putting the author’s name on a book, and along with both of those came the ideology of authenticity—the belief that literary expression must be genuine and original.”

When it comes to breaking the “pact,” James Frey‘s 2003 book, “A Million Little Pieces,” popped into my to mind immediately. Released as a memoir about recovering from alcohol and drug addiction, it was later revealed that parts were fabricated.

People, Oprah was pissed! She had included him in her book club!! She loved his publication…until she learned she’d been duped. Yikes! Frey soon felt the wrath of Oprah. She publicly shamed him on her show for betraying her. She has since apologized to him, but, honestly, there’s a lot of gray area here; I’m not really sure whose side I’m on. (Not that anyone is asking.)

“A Million Little Pieces” was made into a movie by director Sam Taylor-Jackson who said that the controversy “didn’t affect my experience of the book. I enjoyed the creative spirit in which he wrote it.”

(For Frey’s side of the story, check out the video short posted here and let me know what you think about his take on it.)

But I digress.

Drawing the Authenticity line: Cultural Appropriation

OK, so, Frey exaggerated a bit. Maybe a lot. But he was still writing a story that was his, for the most part: white guy with substance abuse issues who did some jail time then straightened out his shit.

What he didn’t do was appropriate another culture for dramatic effect or to sell books. Menand mentions several famous literary hoaxers, including Cyril Henry Hoskin, a British plumber, who wrote “The Third Eye,” which was published as the autobiography of a Tibetan monk named Lobsang Rampa. And, of course, Asa Carter, the former KKK member and speechwriter for George Wallace who, using the pseudonym Forrest Carter, wrote “The Education of Little Tree,” a memoir of a young Cherokee orphan. Not only was that book a best seller and praised by critics, but it was sold in reservation gift stores and taught at high schools and colleges.

Pretendians

I first heard the word “Prentendians”–people so enamored with Native American culture they claim it as their own–from a Native American woman with whom I was discussing a sticky situation I’d gotten into when curating an exhibition of contemporary works by Indigenous artists. In my enthusiasm to create a show I’d been contemplating for years, I neglected to thoroughly vet each artist and, inadvertently, invited a “Pretendian.”

Yes, I’m only human. Everyone makes mistakes, but this one really shook me deeply. I had an Oprah moment: I felt betrayed. Duped. I was angry and embarrassed, but even worse, my lack of awareness betrayed the authentic artists I had set out to honor.

Why are we so eager to accept fakers?

Looking back, I realize I never questioned the “Pretendian” artist’s heritage. I loved the work, believed what I’d read, and called it good.

Menand suggests the reason we readily believe fake claims of cultural identity might be that “Intercultural hoaxes are aimed at [people] who are curious about worlds they have little contact with, and who are therefore easily duped.”

Guilty as charged. Lesson learned. I won’t let it happen again.

Identity Theft: reducing culture to a cliche

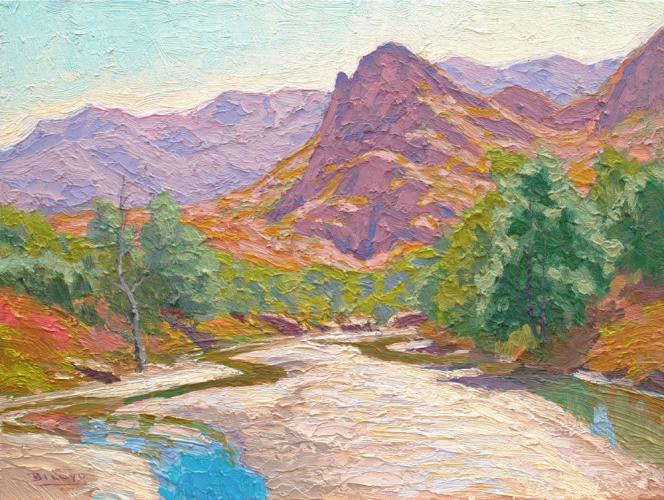

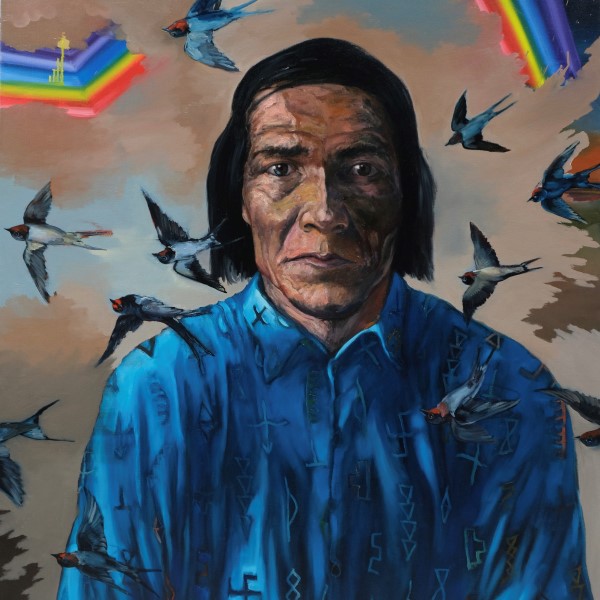

There is yet another kind of appropriation that happens all the time in the Western art genre: white artists whose oeuvre is depicting romanticized images of Indigenous people.

In Western art, this type of cultural appropriation has been widely accepted. It is, I believe, the reason representational art of the western states has long been marginalized in the eyes of the art world.

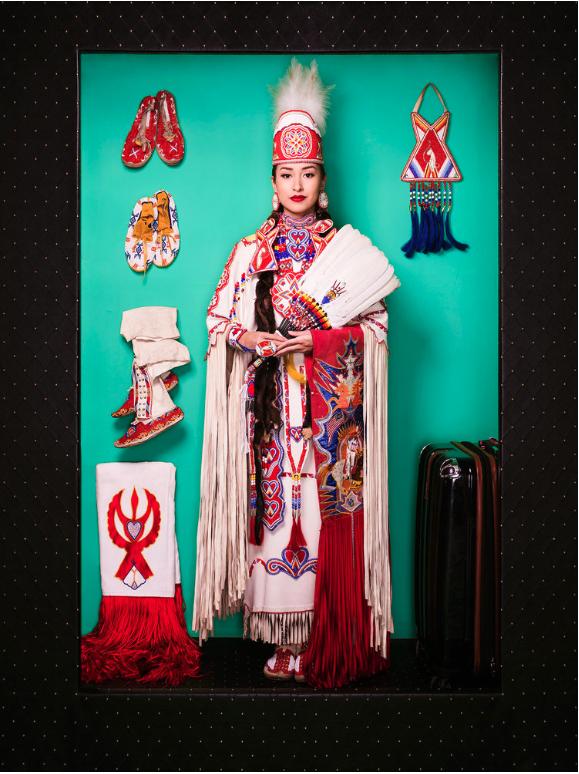

Dakota Hoska, assistant curator of Native American Art at the Denver Art Museum, has been a gentle but firm voice on the topic of cultural appropriation of this kind. She is quick to say she doesn’t speak for all Indigenous people, but she personally finds it to be a kind of identity theft.

“It’s reductive,” she said. “They want to paint our culture but only the part before someone tried to destroy us. Our people were here 13,000 to 50,000 years before white people showed up; we never got to see how our society would have ended up.”

And, worse still, she went on to say, “Romanticized art has the effect of flattening the Native American experience. By romanticizing Indigenous past, we forget about the Indigenous people who lived in each moment in time. This romanticizes an image of an idealized Native person and discounts or devalues the real Indigenous experience at every moment in time.”

"Writing is a weak medium. It has to rely on readers bringing a lot of preconceptions to the encounter, which is why it is so easily exploited."

In the above quote, Menand is referring to literary hoaxes, but art, in many ways, relies on patrons bringing their imaginations to the table, as well.

I’m not saying nostalgic depictions of Native life (that are not even close to how Indigenous people live today) are hoaxes. Well, not exactly. What I am saying is that they do a disservice to Indigenous people by whitewashing a horrific era in our country’s history.

Hoska suggests that perhaps artists who create images of Native people in romanticized scenes are actually searching for meaning in their own life; they want to find connection and think it can be found in an idealized remaking of the past.

But, at the end of the day, it’s still taking someone else’s identity, and, in the process, marginalizing their story. “These artists don’t understand our culture. And, they can’t help but interpret it through their own experience,” she said, and added, “Why don’t they paint what life was like for white people back then? Really, I would like to know why they don’t do that.”

In a video short I’ve included here, Hoska talks with Donna Chrisjohn, co-chair of the Denver American Indian Commission, to share the lens through which many Native American thinkers view Fredric Remington’s stereotypical portrayals of Native people that, as Chrisjohn puts it, “leaves us frozen in time and largely contributes to our invisibility today.”

Sharing responsibility, affecting change

Hoska does see contemporary Indigenous artists making headway, receiving more critical reviews and representation in the market and in museums. “Maybe at one time we needed help telling our story, but now we don’t need Edward Curtis,” she said. “It’s really important that we tell our own story now.”

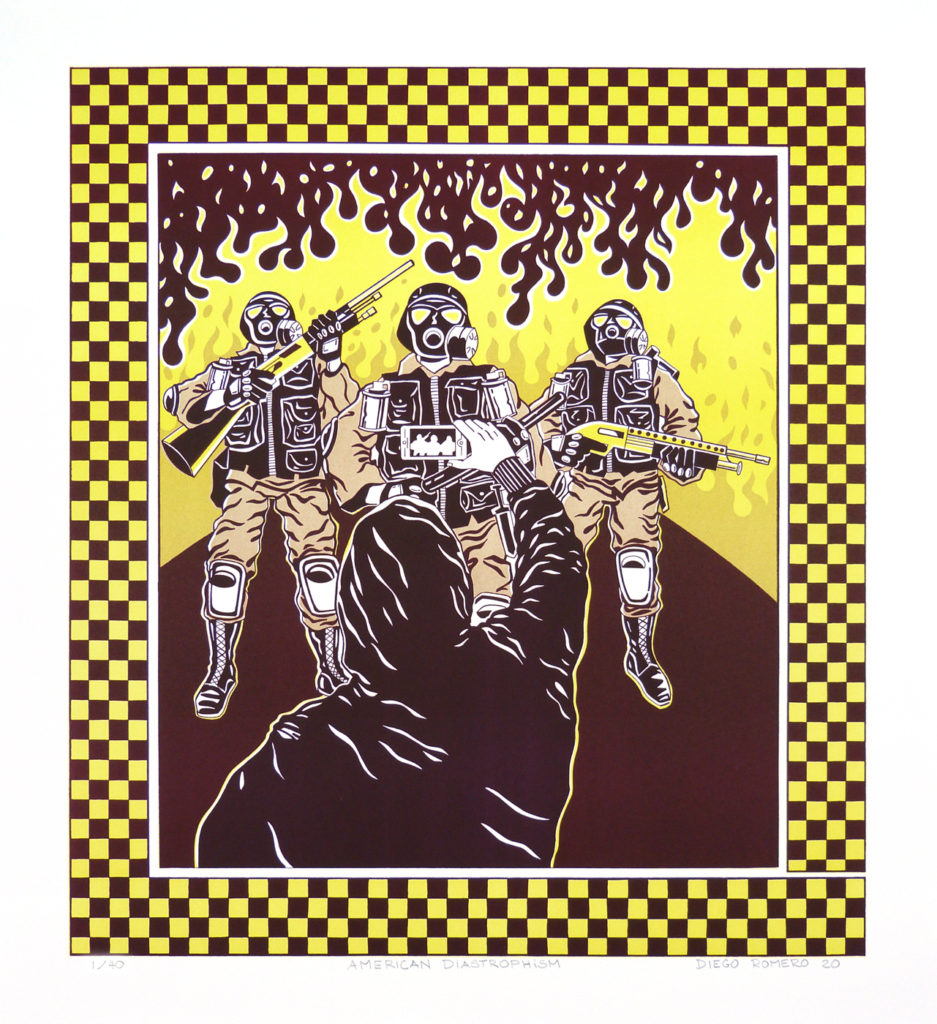

In her curatorial work, Hoska looks for parody as a way to bring non-Native people into the conversation and facilitate an integrated understanding history and culture with art exhibitions that elucidate through authentic, contemporary images of Indigenous people.

In my work as curator for the Coors Show, I believe it is my responsibility to present contemporary artists of all walks of life and allow them to hold the stage and tell their story. I am consistently buoyed by the support of collectors, especially younger collectors, who seek out contemporary, authentic voices.

As for artists, I agree with Hoska when she expressed her belief that their role in society is to seek truth and, as they do so, to continually reflect on the question, “Why do I need to do this work?”

And, more importantly, to ask themselves: Am I making the world a better place?

For more conversations on this topic, check out blog interviews with Sonya Kelliher-Combs, Norman Akers, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Linley Logan, Anna Hoover, Steven Yazzie, Cara Romero, Deigo Romero, Joe Feddersen, Corky Clairmont, andNeal Ambrose Smith.