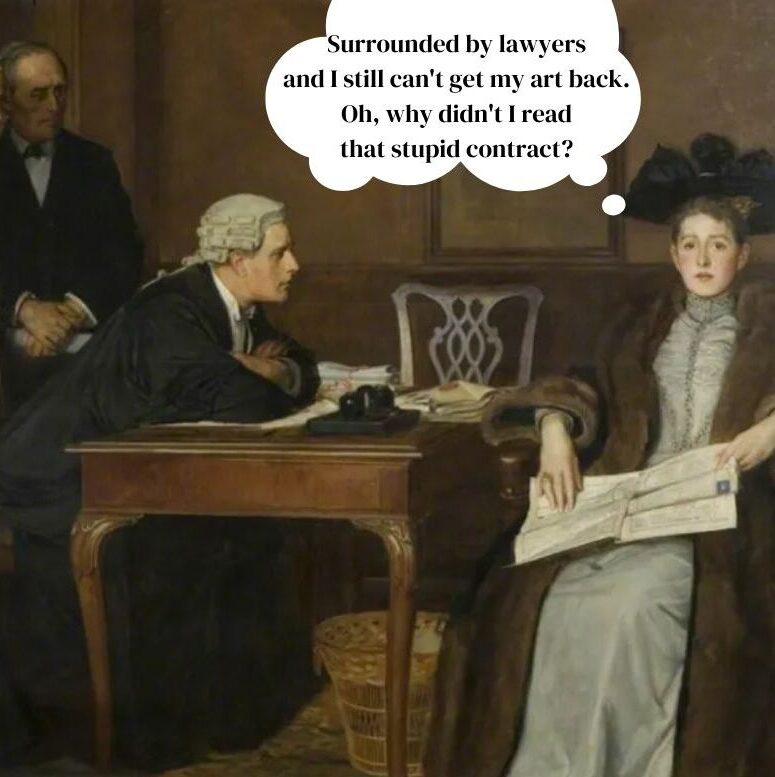

If you’re a collector, chances are you’ve considered selling off a painting or two at auction to free up some space or make a little cash, naturally, to buy more art. Undoubtedly, along the way, you’ve discovered that it’s way more fun to buy than sell.

This time around, I take a deep dive into the world of auctions, bringing you some insider knowledge about how things work, what leverage, if any, you might have, and how to strategically buy and sell in what has become, according to the Wall Street Journal, one of the “hottest markets on earth.”

The Bane of Artists Everywhere

Just to put things into perspective…most collectors don’t realize that auctions are nerve-wracking as hell for artists. I personally avoid adding them to any selling show I work on because I have no desire to put artists in a situation where the work will be undersold and therefore compromised.

I have said this before but it bears repeating: discounting art erodes the artist’s market value. The collector buying at a discount feels they have gotten a good deal, but what they’ve really done is establish that the artist’s work is not worth the stated price.

While work by deceased artists–especially those rare pieces that hit it big–make auctions look like a boon for artists’ careers, the reality is that, for living artists, it’s the place collectors have discovered they can buy on the cheap.

OK, I am now stepping off my soapbox.

The following is an article that will run in Western Art & Architecture, winter 2021/2022. I interviewed collector Doug Erion to get his best tips and tricks, as well as Jennifer Vorbach, former auctioneer and International Director of Christie’s Post War and Contemporary art department, for a little insider intel.

NOTE: I specifically wanted to talk to an auction expert who no longer worked for an auction house. My hope was to get an unvarnished look at the inner workings, which Jennifer provided. To learn more about Jennifer Vorbach, check out her website: JenniferVorbach.com.

Why Auction Results Matter

Did you know that, when establishing valuations for art for most appraisals, auction records play a very big role–a bigger role than I personally think they should (not that anyone’s asking). Appraisals for insurance coverage, a.k.a., replacement cost, are based on retail sales figures. However, for estate, resale, and donation appraisals, valuation is almost solely determined based on auction and previous recorded sales. The difference between retail price and auction results can be astoundingly different.

If you’re thinking this is no big deal, consider that collectors look at those auction records to determine whether your retail prices are appropriate, and thus, whether they should buy your work or not.

And those auction records? They live forever online.

So, how can artists get auctions to support their pricing structure and not hurt valuation by letting work sell below retail?

Unfortunately, I don’t have a good answer. For Blue Chip artists, galleries and/or collectors with a dog in the fight, i.e., a financial investment in an artist’s career, attend auctions, bid up the work, and buy, if necessary. Honestly, I’ve often wondered why galleries don’t do more of this with prominent artists in their sable. Sure it’s pricey, but in the long run it would bolster their artists’ careers.

The Sell-side: Auction vs. Gallery

Auctions are, by art world standards, transparent. Art is put up for sale. It is photographed, condition reported, vetted, and analyzed for value based on myriad details ranging from the artist’s importance to the work’s place within the artist’s oeuvre. By law, the reserve cannot be higher than the low estimate. Sales are done in a public forum, now made global by the internet. Generally, both buyer and seller pay a premium to the auction house.

Gallery sales, on the other hand, are opaque, private transactions. There is a set price for the art, usually decided upon by the artist with his dealer’s input. However, should there be any haggling and deal-making, which can happen along the way to the final transaction, that’s kept on the down-low, primarily to keep the integrity of the artist’s pricing structure intact.

Risk and Reward

For sellers, working with a gallery is often considered less risky. Both collector and dealer agree on the resale price and the commission rate, which can be anywhere from 10-40%. And, while some works of art might have gone up dramatically over the years, most work won’t appreciate to the degree that the collector sees much of a profit after commissions are paid and might even take a loss.

By contrast, auction houses set prices in a range, starting at what can be a terrifyingly low estimate—a number that makes lots of resellers back away. The strategy is two-fold, according to Jennifer Vorbach, former auctioneer and International Director of Post-War and Contemporary art for Christie’s and now a private consultant. “The auction wants to make it competitive, to get as many bidders as possible,” she said. “And it tends to work. Lower starting estimates also allow the auction house to gather and use statistics like, 50% of our lots exceeded their mid-estimates, and 50% sold above the estimate. The auction house then use those statistics competitively.”

Can the seller set the reserve, you wonder? The answer is yes. And no. If a work is of high value and desirable, the seller can negotiate a higher minimum, as well as lower or no premium payment to the auction on the sale, and even receive prime placement in the sale’s line-up (earlier is better, to get bidders while they’re fresh, and the excitement is high). “Everything is negotiable,” Jennifer said, “but if the auction house is not keen on the art, they won’t give you an attractive estimate or even take the work.”

Should you shop work around to several houses to get the best deal? According to Jennifer, if you have a good relationship with one auction, it’s best to deal with the house you know. If you do decide to shop around, she warns, be prepared for competing houses to whisper disparaging things about your art, especially high-profile pieces, something she has seen happen. An auction might cast doubts to steer buyers away from a rival house. “It’s very competitive,” she said.

Perhaps the biggest benefit auction houses can offer over individual galleries is their immense mailing lists and knowledge of buyers. Auctions further create excitement and anticipation for upcoming sales by sending out gorgeous catalogues and posting them online. Plus, the news stories generated from record-breaking sales help add to the fervor.

Fickle Fashion of the Art Market

No matter where you chose to resell art, gallery or auction, you should bone-up on the market before making a decision. Because, while you may think the worst-case scenario is that your art doesn’t sell, the reality is that you may have just “burned” your art.

Auction results are reported publicly, and those reports, as I mentioned earlier, last forever. Anyone can look them up and see how sales went. What they can’t see is why things didn’t sell, or were “bought in.” And so, for years to come, there will be a shadow of doubt hovering over work that didn’t sell, so much so, that should you try to sell the work again, the estimate could be listed lower than your first attempt.

Art is also subject to fashion trends. Jennifer noted how Helen Frankenthaler who, after a major show of her work at the Museum of Modern Art, in New York, suddenly lost her edge. “There was so much of her work in one place,” Jennifer explained, “the works canceled each other out. But, as the art world revolves, other painters of her generation and previously neglected artists—often women and artists of color—have had the spotlight turned on them. Now her work is very much back in demand.”

Blurring the Boundaries: Guarantees and Private Treaty Sales

Over the last two decades, auction houses have crowded into gallery territory in two major ways: private treaty sales and guaranteed sales. Though neither is a brand-new concept, the prevalence has caused a shift in galleries as they respond to the competition. Basically, private treaty sales are done directly between seller and buyer without ever going to auction. The auction has a tremendous advantage over galleries because they have a deep list of collectors to call on, and they know not only who won works by the same artist, but they know the under-bidders. Like galleries, these sales are much less transparent, and they are not reported.

Guarantees are another way auction houses compete with fellow houses but also with galleries by taking out the risk in the sale. Here, the auction guarantees the selling price. If the work of art goes for less than the guaranteed price, the seller still makes his amount. And, if it goes for above the guarantee, the seller not only makes his number, but gets a portion of the upside, as does the grantor. Buyers can see if a work has a guarantee; it will be listed in the catalogue, albeit, in very, very fine print.

Fun and Games: Buying at Auction

OK, seriously, auctions are great entertainment. They have a certain air of a casino attached to them: some art goes big, some craps out. So, what’s the best strategy for getting what you want?

According to collector and auction denizen, Doug Erion, the key is research, research, and more research.

Because of his dogged approach, Doug knows where a lot of work is, which has made it possible for him to swoop in and grab pieces others may not have realized were coming up for sale. Case in point was a Helen Frankenthaler print, one of which resides in the Tate Modern collection. “The Tate has a nice long video about how that print was built,” he said. “Frankenthaler uses many layers; it doesn’t look like it. The video shows how she did this one particular piece. Would I have bought the piece otherwise? Probably, it’s spectacular. But seeing that video and knowing the Tate owns one, pushed it up in my mind.”

It’s also important to note that Doug’s attitude toward auctions informs his strategy. “I go to auctions because of availability,” he said, “not for the lowest price.”

For expensive works, he often calls the auction house and requests a condition report. With prints, which he’s been predominately collecting at auction these days, he’s concerned with foxing or discoloration of the paper. So, if the print is framed and damage not readily apparent, he asks that the frame be removed to confirm the condition. Yup, you can actually do that.

If a piece is not expensive, he will put in a conservative bid for the amount he is willing to pay up to. “If the bidding goes past, no problem,” he says. By doing this, he keeps from getting too invested in the outcome, and so won’t overspend in the heat of competition.

If it’s something he really wants, he will determine the amount he’s willing to pay over and above the high estimate. Sometimes he mans the bidding process, but usually he prefers to have a trusted advisor bid for him, again, with the intention of not going too far over his budgeted amount, unless the situation warrants.

The Bottom Line

If you’re new to auctions or find them frustrating, consider hiring someone like Jennifer Vorbach to help. Often, an expert who knows her way around the auction scene can work magic, open doors, and even find things you haven’t had any luck tracking down on your own. At a minimum, understand that reselling work is not as easy as buying so do your homework, ask questions, and learn how individual auctions work (terms vary from house to house). Most importantly, set realistic expectations.

5 thoughts on “How to buy and sell art at auction”