The fine art print market is a great way to start collecting. But it is a complex art form that requires buyers to understand some technical aspects to printmaking.

For beginning collectors, prints are an easy way to buy nice works by substantial artists at prices that won’t stop your heart. For seasoned collectors, the print market is a fabulous way to acquire works by deceased artists whose paintings regularly sell at auction for staggering sums.

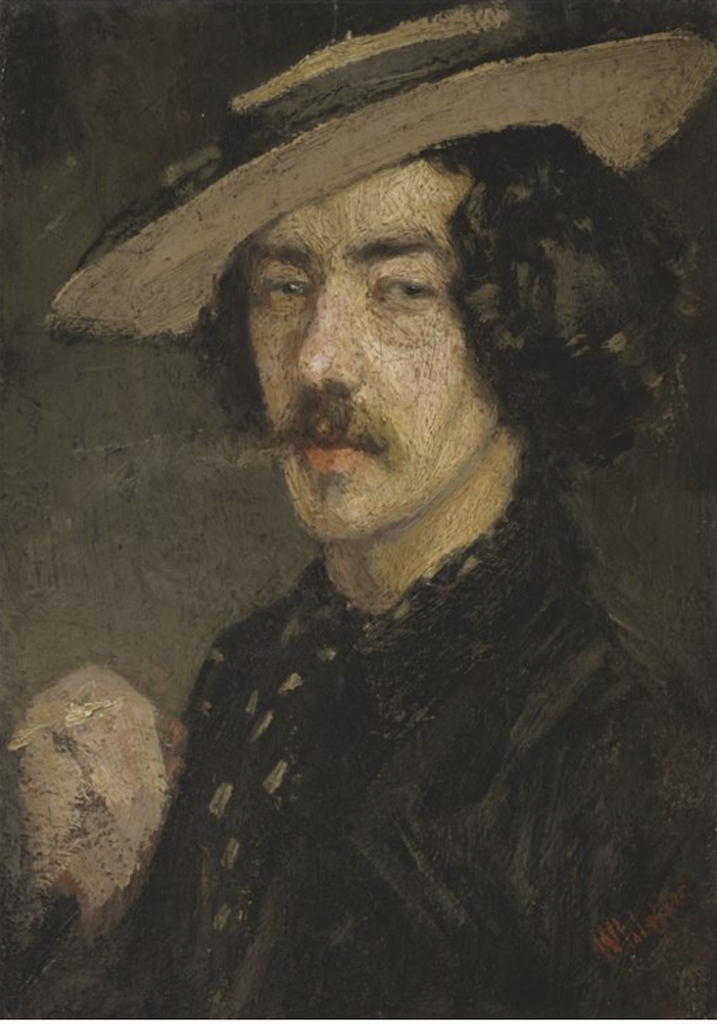

Consider James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834-1903). In 2020 at Christie’s British and European Art sale in London, Whistler’s 5 x 8.5 inch watercolor, “Chelsea Shopfronts,” sold for $79,840 (buyer fee included). And the following year at Christie’s New York 20th Century Evening Sale, his oil painting “Whistler Smoking,” 9.5 x 6.63 inches, sold for $1.2M. Whistler’s paintings rarely come up for sale, but his print work shows up frequently on the secondary market. That’s because, during his lifetime, Whistler made more than 400 etching and dry point plates and some 150 lithographs, which means there are multiples of those 550 or more images out there in the world, many selling for $1,500 to $28,000.

It’s basically supply and demand: Whistler paintings are scarce; his prints are not.

Affordability and Accessibility

The earliest known prints date back to sixth- and seventh-century Egyptian wood block prints on textiles and eighth-century Japanese relief prints. Since then, other printing processes have been added to the mix, which has opened up this art form of “original multiples” and made it accessible and affordable for both artists and collectors.

But wait, artists should or shouldn’t make prints?

OK, I’m going to split hairs here. Prints in their various hand-pulled forms are works of art in and of themselves. Mechanical prints such as giclees are reproductions–facsimiles–of original works of art; they are not the original works of art.

There is an important distinction to make when looking at prints: manual versus mechanical; human versus machine. In order to figure out the difference, it’s good to start with a little background knowledge.

Printmaking 101

Manually pulled prints can be created using various means. The oldest prints were done as reliefs where a raised design on, say a carved block of wood, is inked, paper laid on top, and pressure applied to transfer the ink onto the paper. The second oldest form is intaglio, meaning “incising or engraving.” In this method, the image is etched into a plate, ink is pushed into the engraved lines, the surface wiped clean, paper laid on top followed by blankets, and then the whole kit-and-kaboodle is run through a press with heavy pressure, causing the paper to absorb ink from the incised lines. This process leaves a plate mark when the paper dries (check out the sidebar for more tips on discerning prints).

Here’s short video that shows you how intaglio prints are made. Pretty cool.

This video explains lithography.

The third process, which is more recent, is known as planographic or surface printing—we’re talking lithography. This is done on a litho stone or flat metal surface. The idea here is that water and oil don’t mix. An image is created on the surface in oil that is chemically manipulated to accept ink. Water is then applied to the surface so that when the ink is rolled across the image it only adheres to the oil. Next, paper is set on top, run through a press, and voila.

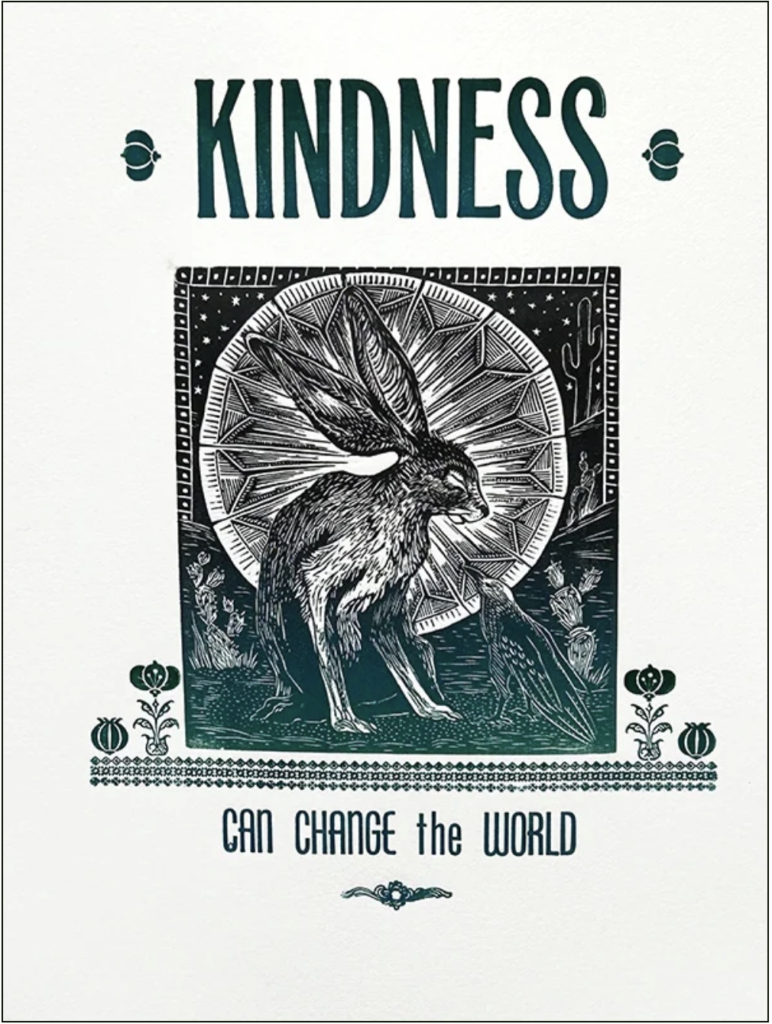

Screenprints and monotypes are the most recent printing processes. Screenprints are essentially large silk screens where the image is masked off. Ink is pulled over the screen so that it falls evenly onto the paper. Many layers of colored ink are used to create one image and, as a result, you can usually see the ink laying on the surface more readily than in other printing processes. Monotypes are “mono” because there is only one—technically. The artist does a painting on a flat surface—plexiglass or copper, for example—damp paper is laid on top of the painting, then the whole thing is run through the press. A mirror image is pulled, leaving a ghost image behind. The artist can go back over the ghost image and change it, re-ink it, and run another print, though it will be noticeably different, thus a new monotype.

How to print serigraphs like Warhol.

Quick Monotype demo.

And, just to make this all a little more challenging, lots of these processes can be combined to make an image. All-in-all, printmaking is deceptively complicated and quite possibly one of the most underrated art forms.

The final category of prints are mechanical. Machine made off-set lithography, which is how this magazine you are reading was printed, and giclees are the most common, which brings us to the downside of printmaking for artists. (Giclee is a French word meaning “to spray,” which refers to the inkjet process of spraying ink on paper to reproduce art.)

More Isn't Always Better

Supply and demand does play into pricing art. Paintings are singular. Yes, artists can riff off the same image, but those are all new paintings. Hand-pulled prints come in multiples (except monotypes, which, as stated already, are unique paintings run through a press). Prints are numbered; however, hand-made prints tend to have lower numbered print runs because the plate or silkscreen simply wears out. With wood cuts, the artist may have one or two plates for an image, but that plate is run through the press multiple times and for each new color—some images have upwards of 20 color changes—the wood block is further carved away so that, by the end of production, the plate is destroyed.

Machines that make prints, however, do not wear out—well, not in the same way traditional printmaking tools do. And beyond the photographer who took a high resolution photo of the art and the pressman who oversees the printing, there isn’t any human contact.

Competing Against Yourself

And now we get to why I suggest artists who are not traditional printmakers should not make prints (giclees).

With giclees, an artist can flood the market with reproductions of individual paintings. For new artists scrambling to pay rent and buy groceries, the promise of making a hundred bucks off a giclee sounds like salvation. You can practically sell them off your website while you sleep! What could possibly go wrong?

While these prints are incredibly accurate reproductions of paintings, they actually create a troubling side effect: artists start to compete against themselves. In the art market, at a certain price range, lots of art buyers can’t tell the difference between an original and a giclee and so, think, why pay more when the print is so good? Established collectors, however, know this is the equivalent of buying a Farrah Fawcett poster: totally rad, dude, but not the real thing.

So, when it comes to prints, scarcity and the human touch create value. Mechanical prints are beautiful but won’t hold their value. Manual prints, however, will because each print was—wait for it—hand pulled through a press. This is where being a flawed human is actually kind of a bonus. The savvy print collector looks for works pulled by specific master printers at certain presses that coincide with the era of the artist. Craftsmanship counts: you want to see the hand that built it.

Become a Savvy Print Collector

If you think you want to collect prints, we highly recommend educating yourself on the various printing processes. Bamber Gascoigne’s book “How to Identify Prints, a complete guide to manual and mechanical processes from woodcut to inkjet” is invaluable. Visit some print fairs to see works up close and ask experts to explain what you’re looking at and why it’s priced as it is. There are myriad issues to consider before buying prints, but it all starts with identifying what kind of print you’re looking at. Once you invest the time to really learn about prints, you can find truly valuable pieces at estate sales, consignment shops, and antique stores. Check out the sidebar for telltale signs you’re looking at something of value.

How to Find Hidden Gems in the Art Market

- Rule out mechanical prints. You’re looking for a regular dot matrix pattern. This is a dead giveaway. You might need a magnifying glass (a loop with 4x magnification) to see the pattern of dots. It will look a lot like the Sunday comics in newspapers.

- Plate impression. You can easily see where an intaglio plate left an impression around the outside of the image. These images are almost always one color—black or sepia. If there is color, that may indicate that the artist painted on the print, making it a unique work of art.

- Color could also indicate lithography, serigraphy, or mechanical printing. Sometimes, if you look from the side of a print, you can see a layer of ink floating on the surface. This would indicate a monotype, lithograph, or serigraph. Again, look for the dot pattern, when in doubt.

- Double signature line. If you see a print with two signatures, one within the painting and another on the white paper border, it’s probably a mechanical print. A high resolution photo was taken of the painting—signature and all—and used to create a digital file that was then run on a mechanical press. The artist then signs and numbers these pieces of paper, indicating it’s a reproduction of the original.

- Single signature line in pencil. With hand-pulled prints, the artist’s signature will be written in pencil, usually along the bottom of the image. There will also be a title, often centered below the image, and edition numbers indicated by a number over another number.

- Edition numbers. With hand-pulled prints, the first number is the individual piece number, and the second number is the total number of prints that were pulled. So, 21/50 means you have print number 21 out of a total of 50 prints. Look for low numbers. If, however, the number is above 100—say, 1,200, for example—those are mechanical prints. No plates or screens can hold up to that amount of re-inking and runs through a press or scrapes of ink across the surface.

- Edition letters. You might also see things like “AP,” which is an artist proof. “PP” is printer’s proof, which are proofs given to the print studio. “HC” prints are hors commerce prints, meaning “out of trade.” They are only given out by the artist and are quite rare.

- When selecting prints, inspect them carefully. You don’t want to buy things with tears, creases, foxing or discoloration caused when a print was exposed to oxidation or acidity, usually from exposure to wood pulp from inferior matting. Some condition issues can be corrected, so it’s worth asking a conservator first.

7 thoughts on “Why Collectors Should Buy Prints (but artists should not make them)”