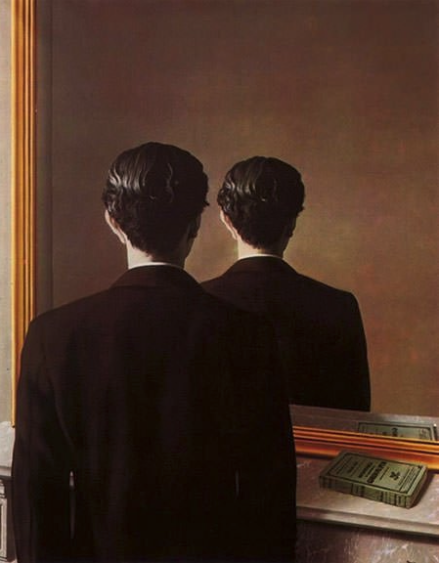

I’ve had, for years, the strangest surrealist moments sparked by catching a glimpse of myself in a mirror or reflection in a shop window. It can be startling, this dissociative, out-of-body experience, wherein the image before me does not correlate with the image in my mind’s eye.

Plainly put: I don’t know what I look like.

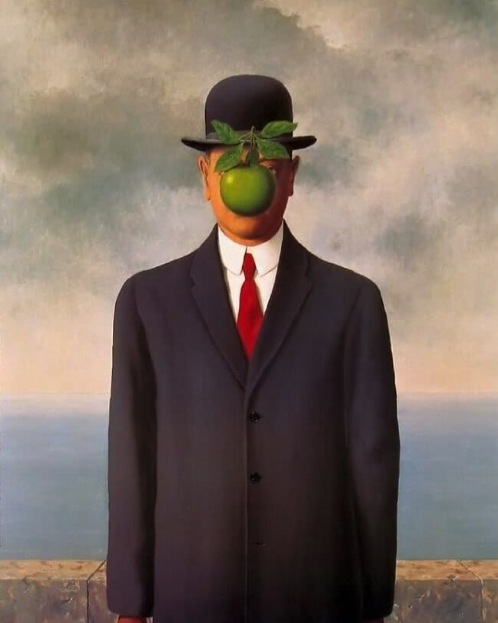

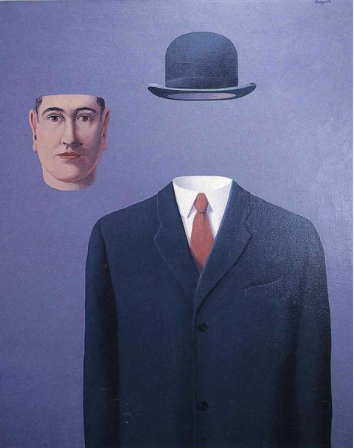

It’s as if I’ve been blocked out, like Rene Magritte’s (1898-1967) figure behind the apple in “Son of Man,” and only know my face as the apple. Then, on occasion and for reasons unbeknownst to me, the apple disappears, revealing a face I hadn’t expected.

Magritte’s explanation of this painting may shed some light:

“Everything we see hides another thing. We always want to see what is hidden by what we see. There is an interest in that which is hidden and which the visible does not show us. This interest can take the form of a quite intense feeling, a sort of conflict, one might say, between the visible that is hidden and the visible that is present.”

When Art Imitates Life

Studies indicate that both men and women spend nearly an hour a day looking at themselves in a mirror. I’ve never timed myself but suspect I’m not all that different. So why, I’ve often wondered, is my reality so skewed from my internal knowing?

From the website, ReneMagritte.org, here’s an interesting bit of insight into the artist’s train of thought:

“…what is concealed is more important than what is open to view: this was true both of his own fears and of his manner of depicting the mysterious. [His paintings were] not so much to hide as to achieve an effect of alienation.”

Right. So, according to Magritte, I’m actually being startled by “the visible that is hidden”?

Dang. Those surrealists were deep.

Alienation

During WWII, Magritte lived in German-occupied Belgium, apart from his fellow surrealists who remained in Paris. Feeling alienated and abandoned, Magritte supported himself by painting fake van Goghs, Picassos, Cezannes, and others.

I wonder about this choice, to be a forger as means of survival. Was it simply an obvious way of making money? Or was it part of Magritte’s journey deeper into his own vision? Would his own post-war works have been as poignant had he not forged paintings in the manner of these artists? Did the act of creating forgeries help him understand something essential about each person he emulated, thereby unearthing elements of his own personality?

Or maybe he just kicked ass mimicking others and didn’t want to starve to death.

Oh! OK, fun fact: Magritte got so good at forgeries that he was able to create fake bank notes during the occupation, which he and his family lived on. And, apparently, the forgery biz was so lucrative that Magritte’s brother, Paul, took over when Rene went back to making an honest living. Who knew?

The war undoubtedly affected Magritte, but not his form of expression. Surrealism was the visual dialogue introduced to him in Paris by Andre Breton, the founder of the movement, years before the war, and the style Magritte rarely if ever strayed from. Magritte insisted that his work was meant to push viewers to question their sense of reality and become hypersensitive to the world around them.

I would add that his paintings force the viewer to become hypersensitive to the world within, as well.

Hidden in Plain Sight

As straightforward as Magritte’s comments about each work are, there are still layers to peel back.

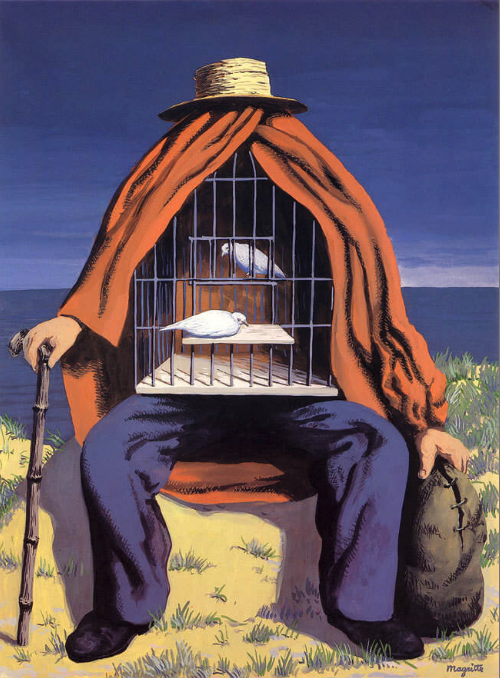

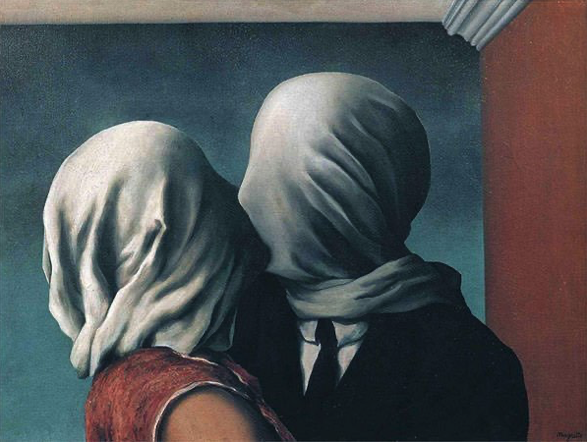

Like the shrouded figures. Some suggest that these stem from memories of seeing his drowned mother, who had committed suicide, pulled from the river near their home, her dress covering her face, like a shroud. Magritte was 13 when he witnessed this.

I’m not a scholar on Magritte but I do wonder how much of his work, if any, is about something other than his past and this loss.

Learning to See

Viewing art is not a passive act. The viewer may be standing quietly, absorbing images, but inside neurons are firing, electrical impulses are kicking in, surging through the body, in particular when memories are triggered, reminding the viewer of something personal. Here’s an interesting article about all the amazing things happening in the body when viewing art: Art Enhances Brain Function and Well-being.

For me, Magritte’s work triggers an internal recognition, a jolt from a kindred spirit in pursuit of the real within the obscured or shrouded, a connection to the floating parts of ourselves, light signals from the transfigured imagination.

Baggage Is Part of the Experience

I’ve lived with this sense of not knowing what I look like or, worse, believing that I’m sitting in an important meeting, not as the middle-aged professional curator I am, but as a pudgy child with stringy hair and bad skin.

I see, in my head, the frumpy, naive girl my mother always told me I was. (Still, to this day, given the opportunity, she never misses the chance to land a blow with an abusive jab.)

For much of my life, the surprise was looking in a mirror and not seeing that girl.

This personal dogma is what I’ve bought to the mirror and carried throughout my life. When told anything counter to this belief, I rejected it out of hand, certain that these flatterers were idiots and scammers.

And then, for some reason, the world shifted during Covid; disassembled “me” began to pull together.

The True Gift of Art

I tossed out the word, “dissociative,” not to be hyperbolic but to express this weirdly surreal aspect of my nature, this not knowing my own image in a mirror. It’s a strange thing to believe what others say about you to the point of losing yourself, and yet I know so many people experience this. It’s how we lose our way in this life.

Art, artists, and therapy have helped nudge me toward a rethinking of my beliefs, so that the most tender spots in my psyche can be examined and healed.

And, as strange as it may sound, when I work with artists on marketing, we always start by excavating their “why.”

On the surface, this is because I can’t help a person market what they themselves cannot recognize. Yes, every artist can talk about materials and technique, but that’s not what collectors are buying. Collectors are buying an idea. They are buying a piece of the artist.

It’s an amazing gift to be present with creative people as they take on the task of self-interrogation. The process can be messy and emotional and confounding (much as my own self-innterogation has been), but always the journey back to center–back to the reason one became an artist in the first place–is such a glorious awakening.

Freeing the Artist Within

I have come to believe, thanks to many candid conversations with artists, that the act of making art, in its purest sense, is self-interrogation. If the artist is being true to his or her nature, every painting, photograph, or sculpture is a self-portrait. Sometimes these self-portraits are so revealing they are terrifying. And yet, the artist persists.

Art is also a kind of panacea, a prescription for a drug that pulls one closer to his or her core being. No artist can predict who will take what message or cue from a work of art; that’s not the point of it, really.

The point is to expose the artist’s self, and through that act, the viewer can finally set down her baggage, look in the mirror and see the person who was there all along.

If you’d like to continue this conversation, please leave a comment below. And feel free to share my blog with friends.

If you are interested in looking into marketing for artists, please reach out and contact me to discuss further.

16 thoughts on “Standing Next to Myself, with Questions”