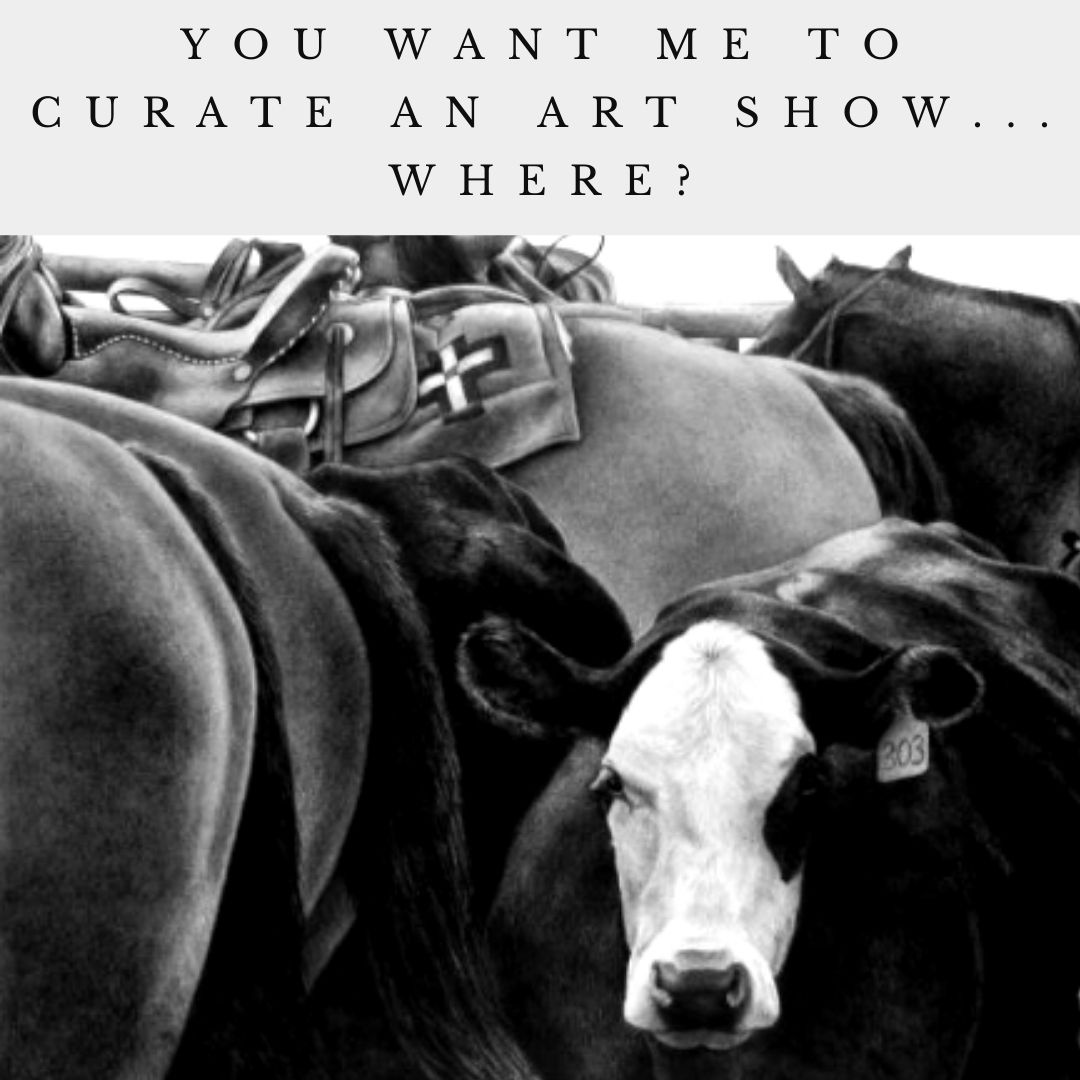

In the summer of 1996, I was hired to curate a small, regional show in Denver, at the National Western Stock Show. During the Stock Show and Rodeo. In January.

I had never been to either the fledgling Coors Western Art Exhibit & Sale or the Stock Show, but the idea of an art exhibit in such an off-beat, unexpected venue struck me as a unique and exciting challenge.

Obvious hurdles aside, (a blizzard shutting down the city on opening night, for starters), I enjoyed puzzling out the curatorial questions that came with this show, such as, how do I get successful artists to participate in an exhibit held at a stock show and rodeo? How is Western art defined? Is there room to broaden the conversation within that definition? Could I invite artists who didn’t create traditional fare but were technically “western” artists because they lived and worked in the West?

Could I, I wondered, blur the lines between traditional and contemporary art?

What’s Scarier Than Naked Women?

Back in the early days, the Coors Show was flying under the radar. I took this opportunity to try out my theories about pushing boundaries with artists whose work didn’t fall squarely within the stricture of “Western.” It helped that I had few guidelines to follow beyond finding living artists whose work reflected the Western way of life. We were a fine art show that included photography but not crafts such as pottery. Oh, and no nudes; strictly PG.

Taking on an unknown show at an unproven venue meant that I had little or no shot at getting the big names in traditional Western art. Yes, I tried getting them, but they were busy or didn’t return my call. I couldn’t blame them. The Autry had the Masters of the American West, and the Cowboy Hall was killing it with the Prix de West. Great exhibits that showcased the best in traditional Western art. The tiny Coors Show simply could not compete.

I rang up old friends, explained my idea of opening up the conversation about the West and the art that’s being made here, and was able to get Len Chmiel, Skip Whitcomb, George Carlson, Steve Kestrel, and others to come on board. They lent their good names and reputations to help me jumpstart the show. Lots of artists who saw those names on the roster gave us a second look. Still not the traditional artist, though. But I was OK with this. I had other ideas in mind.

Two Roads Diverge

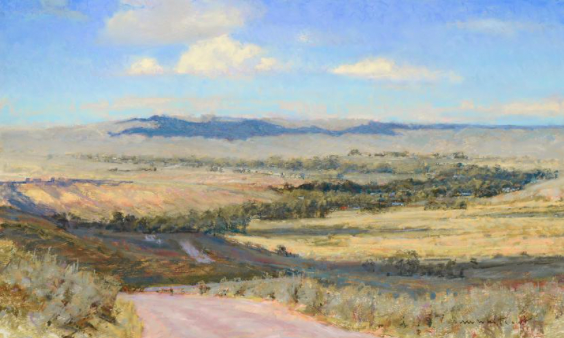

In the art world, when you toss out the word “contemporary,” people hear things like “abstract,” “challenging,” “confrontational,” and “hard to understand.” Say “Western” and slap “art” onto it, however, and people see illustrative works that tell stories, ala Charlie Russell and Fredric Remington. Western is definable; you know it when you see it. Contemporary, well, that’s out there in the wilderness making stuff up and getting all emotional about it.

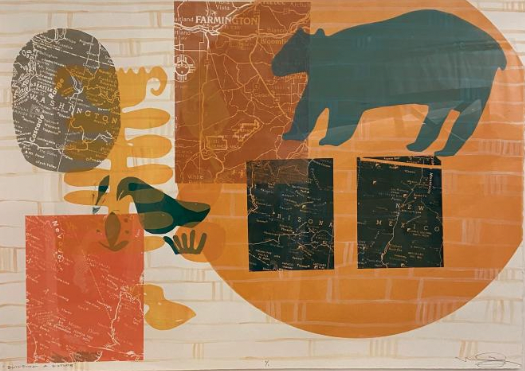

Despite the rift between philosophies—traditional vs. contemporary—finding a singular path for the Coors Show was top on my list. I wanted artists who were the best at what they did, who took on subject matter with masterful skill and conviction. I wanted artists who were unafraid to be authentic, even vulnerable.

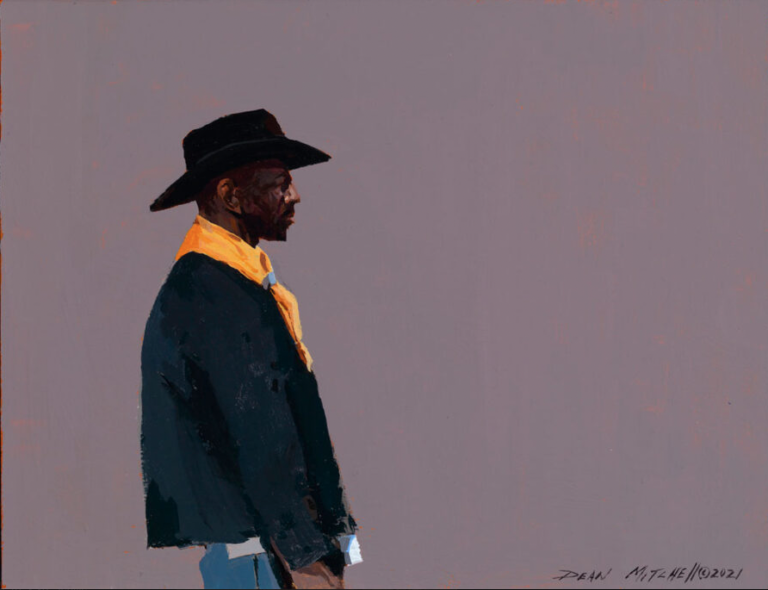

The other thing I really wanted to build was a show that gave voice to our great artists who didn’t fit neatly into either traditional or contemporary venues. I wanted to show Daniel Sprick and Dean Mitchell alongside William Matthews and Barbara Van Cleve.

More importantly, I saw a niche in the market no one was tapping into: a contemporary-realist focused exhibit about the West. The only catch was I couldn’t use the word “contemporary.” Not at first, anyway.

How to Offend a Curator

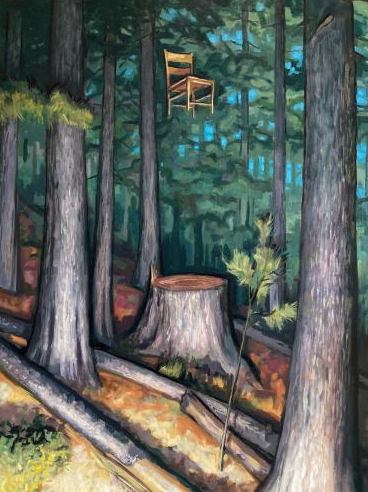

I look at the art of curation much like throwing interesting dinner parties where disparate guests discover they have a lot in common. Or things devolve into fisticuffs. Either way, I’m happy. The idea of curation, in my mind, is to create opportunities for conversations that get people talking. Even better, opportunities to show my audience their familiar surroundings in a new way. Putting contemporary art alongside traditional work, well that, my friend, is a heck of a dinner party!

I will admit, my open arms approach has ruffled a few feathers. I get it; art is personal, but the extent to which some folks have gotten upset about art, at times, has surprised even me.

One of my favorite stories happened the year I hung Theresa Elliot’s hyper-realistic cattle paintings (think the Mona Lisa, if she were a cow), across from Ted Waddell (think Motherwell meets cattle). An old rancher came in, found a volunteer to let her know he was there because he felt he needed to come see the art show each year. She graciously welcomed him and let him know she could help if he needed anything. Not too many steps into the gallery and he was confronted with Theresa and Ted. He stood there a long while then went back to the volunteer and made her join him between the works. He pointed to Theresa’s paintings and said, “These paintings are incredible.” Then, turning to Ted’s work, he said, “But these! These are a colossal waste of paint!”

The volunteer was afraid to tell me this story, but when she did, I hugged her. This is what curators live for: eliciting a response, evoking emotion. That rancher really looked at the art and had a reaction. Western art got under his skin and made him feel something!

When was I offended? That happened when a local art critic whose opinion I valued (and still do) wrote something to the effect of, “the show is filled with bucolic paintings.” Bucolic! Here again the volunteers who happily taped the review in the breakroom at the gallery, were stunned that I’d taken offense. Bucolic. She might as well have said I lulled patrons to sleep with my vanilla curation.

After that review, I redoubled my efforts to bring interesting and thought-provoking work to my audience. Not to offend, I really don’t want to offend anyone, but to present ideas and a unique lens with which to view the familiar.

Crossing the Line

The amazing thing about having a show in a non-traditional setting like the National Western, is that nearly 40,000 visitors from a diverse cross-section of our western population stop by. Because our audience is made up of people who live and breathe the western way of life, I believe we owe them authenticity. Traditional or contemporary—these things are stylistic choices. Authenticity is a core principle. The very nature of being an artist is to take on subject matter with masterful skill and conviction. But also, to be unafraid to be authentic, even vulnerable.

Many Coors Show artists were born and raised in a traditional western home. Don Coen, for example, grew up in Lamar, CO on a working ranch that, until he turned 12, had no running water or electricity. His only complaint was that he had to ride a horse to school—all his friends had bikes. But Don, like others in the show, puts the exploration of what it truly means to live in the West first. He knows why he’s creating this work: it’s intrinsic to who he is and decidedly not what he thinks the market wants.

Another tenet of my curation: if we’re going to show work about Native Americans it needs to be created by Native American artists. In a conversation with Denver Art Museum assistant curator of Native American Art, Dakota Hoska, on the triggering effect of traditional Western art that depicts Indigenous people in historic settings, she said, “Romanticized art has the effect of flattening the Native American experience. It’s reductive. They want to paint our culture but only the part before someone tried to destroy us. Our people were here 13,000 to 50,000 years before white people showed up; we never got to see how our society would have ended up.”

And, as Donna Chrisjohn, co-chair of the Denver American Indian Commission, said of Fredric Remington’s stereotypical portraits of American Indians, “it leaves us frozen in time and largely contributes to our invisibility today.”

These days, I ask why. Why is an artist doing this work? Why now? Why are they the ones to tell the story? As curator for the Coors Show, I believe it’s my responsibility to present contemporary artists of all walks of life and allow them to hold the stage and tell their story. I am consistently buoyed by the support of collectors, especially younger collectors, who seek out contemporary, authentic voices.

Looking to the future, I would love to see more open mindedness and space for alternative—yes, contemporary—voices to be heard. I truly believe, for Western artists, this is the only way our genre will be recognized in the larger arena and ultimately, stay relevant for the next 100 years.

13 thoughts on “Making a Case for Contemporary Western Art”